Words GAMALL AWAD

Ben Vida’s most recent release is the four-hour epic Reducing The Tempo To Zero, which Shelter Press released on a USB card — limited to just 150 magnetic cases — last December. He premiers a new work (“Always Already”) with soprano Nina Dante and percussionist/pianist quartet Yarn/Wire at New York’s ISSUE Project Room tonight.

In the spirit of Vida’s sprawling new album, we conducted an in-depth interview with the ambient/experimental composer, the first part of which focused on three key influences from the Reducing the Tempo To Zero sessions….

GEORGE MILLER – MAD MAX: FURY ROAD

Head in one direction. Stop. Turn around. Head back. This is the formal proposition of the film. Once you get this as a viewer, you can set it aside and dig in to enjoy every little detail. The visual language is so dense at times that it almost becomes a blur, a drone. This films feels like one wonderful gesture made up of a million perfect elements.

MORTON FELDMAN – STRING QUARTET NO. 2

String Quartet No. 2 runs just over six hours. At this length, memory becomes a compositional material. How much is the listener able to retain in their memory in terms of form? As I listen to this piece, the sense of forward moment often disappears and I become enjoyably unmoored.

“Up to an hour and a half

you think about form,

but after an hour and a half

it’s scale.” —Morton Feldman

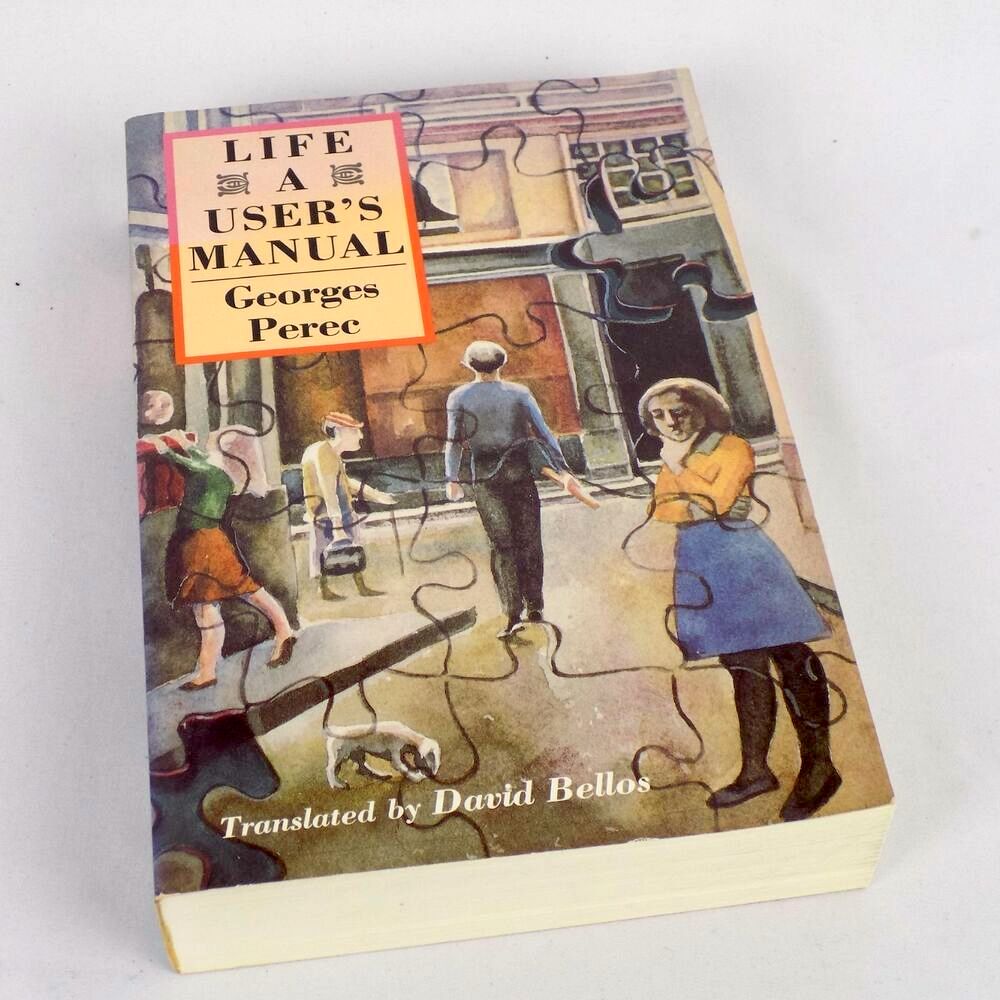

GEORGES PEREC – LIFE: A USER’S MANUAL

Everything that is happening in a single moment — 8 p.m. on June 23, 1975 — within an apartment block in Paris. A static form where all the grains of a moment are to be explored. The composition takes shape though storytelling, histories, list-making, and endless descriptors. This becomes a space of receiving through the vertical. Like strata.

Life was written using a complex set of self-imposed constraints that were used as a means of triggering ideas and inspiration. How does his approach relate to your new composition?. If you used constraints, what were they?

I wouldn’t say that a method of using self-imposed constraints had that much to do with RTTTZ beyond perhaps my sticking to certain aesthetic parameters. And really those arose more out of simply setting up a situation in my studio where I was just totally living inside the drones for days at a time and really enjoying myself.

In general — certainly in regard to projects I have done in the past — predetermining a system of production, or setting certain constraints, has helped me to clear away a lot of the extra considerations that might dilute the original intention I have for a piece. Being in the studio is making one decision after another. Finding methods that can direct this decision making into unknown territories is helpful.

In the preamble to Life, Perec discusses jigsaw puzzles, saying, “The pattern determines the parts; knowledge of the pattern and of its laws, of the set and its structure, could not possibly be derived from discrete knowledge of the elements that compose it.” These words seem to fit your composition. What do you think about what he is saying here as applied to working with electronics?

For me this speaks to allowing the intention of a piece to determine how it manifests, but also how the internal logic of a composition effects how it is initially received even if that internal logic isn’t immediately revealed. This also makes me think about micro/macro perspective shifts and how being able to toggle between different perspectives while still in production is so important. I feel like I am always playing with the threshold between what can be received and what gets lost in terms of fidelity. I know that any one element will not carry the whole of a piece forward. And even though I enjoy getting into the fine tuning of each moment that synthesis and processing allows for, it is the summing of these collected moments that is actually what the listener is most likely responding to.

Perec was a part of the experimental collective Oulipo (Ouvroir de litterature potentielle, or the Workshop of Potential Literature) made up mainly of writers and mathematicians. They were told to seek out “new forms and structures that may be used in any way they see fit.” I’m wondering how much this mandate fits what you do as an artist working across several disciplines?

I mean, this is really it. Problematizing work on a formal or structural level is a great way to confound your subjectivity and begin to ask new questions. So much of why working across disciplines is interesting to me is that producing iterations of an idea in different mediums helps to reveal more about that idea to me. It becomes generative.

Do you feel you are part of a broader alliance of people working in a related way? If so, who, and where, are those connections for you, and how have they brought you to this moment / inspired your creativity?

It comes and goes. I feel fortunate to have been able to have been in proximity to a lot of different creative people over the years. There are periods of feeling a real resonance with a group of folks and then, in time, moving on and finding camaraderie and inspiration elsewhere. I love to collaborate and it really is how most of my good friendships have begun.

Perec’s book is as much about architecture as it is anything else. Your composition also has an undeniable air of the architectural about it, but you’ve moved from New York to Woodstock, so the architecture around you has changed. Can you talk about this move and about the influence of architecture? Beyond that, how does space itself impact your work, sound, and approach? It would be great if you could elaborate on the “strata” idea you brought up earlier and how you use it in your work.

The move from New York to Woodstock had a lot to do with just allowing for my senses to really open up on a creative level. To access a finer grain of receiving and to recalibrate to tempos determined by things other than human insistence.

I go back and forth almost every week since I still teach in the city, and New York continues to be a major part of my creative infrastructure. I enjoy the shift in tempo that accessing both places allows for. I really get into the compression of the city and also that feeling of opening back up once home on the mountainside.

Look out for the second part of our interview with Ben Vida next week, and check out one of his past ISSUE Project Room performances below.