Interview by John Doran

Check out the first part of our extensive Chris & Cosey interview here, or click this for an exclusive mix featuring the iconic couple and Factory Floor’s Nik Void.

And now, for the rest of the story, including Chris & Cosey’s thoughts on Throbbing Gristle’s most infamous records and shows, their highly influential material as a duo, and the status of TG’s take on Nico’s Desertshore album…

How much of the sinister, occult, violent nature of Throbbing Gristle was due to the personal headspace of the group and how much of it was down to the lifestyle of living in Martello Road in Hackney, which I’m guessing was a very rough area at the time?

CFT: It was both of those things. That’s what we did and still do now to a certain degree. We simply exorcise what’s inside of us via sound.

CC: I know it’s a cliché but it was a reflection of where we were living and how we were living at the time.

CFT: It was a reflection of our emotional state, our psychological state and also how we wanted to communicate with people–to communicate our anger and frustration.

CC: Hackney in the 1970s was a heavy place to live with heavy police presence, the SPG (a notoriously corrupt rapid response squad of the Metropolitan Police) and the gangs.

CFT: There was a lot of interracial violence.

CC: There was a lot going on; there really was. And that was aside from what was going on in the band–the tension that had. All those things are reflected in the music.

CFT: And everyone was poor and fighting for their rights and space in a society that was absolutely crippled. So if you think of it like that you can understand where the TG sound comes from.

I think it’s quite interesting that Hackney and North East London is where the slightly less well-off artists and musicians have always gravitated towards. Today’s batch in Dalston might not match up, but the tradition continues nonetheless. I was wondering if you were completely isolated or were you part of a wider counter-cultural scene? Did you know Iain Sinclair for example?

CFT: We didn’t know Iain Sinclair then.

CC: In the Martello Street Studios, there were a lot of artists that knew each other.

CFT: But we were like the outsiders. We always have been. Because back then–and even now–a lot of the artists I knew had a day job lecturing. It’s something that we’ve never done because we’ve put our whole life towards our work because that’s our focus. We don’t have a safety net because when you operate without a safety net that’s when interesting things happen.

CC: At Martello Street Studio most of the artists in the building were actually artists whereas TG–who had previously been COUM–were moving away from art and were disassociating ourselves from art. And a lot of the people we knew were actually in other bands in Sheffield or Manchester.

I do think it’s one of the great failings of a lot of bands today that they don’t have a background in art. You have groups who have all the signifiers of an ‘art’ band but none of the understanding, or perhaps they even have an innate fear of art. I think this is where industrial music went wrong. I guess it must have been easier for you to get on with other artists on this score.

CFT: You say a background in art, but none of us had the certificate on the wall to say we were artists.

But you were used to performing in art galleries:

CFT: But even within the art world–when Gen and myself did performances or whatever–we were still the outcasts because we didn’t have the qualifications and were considered interlopers. But that appealed to us because we believed that you didn’t need that certificate and that everyone has that ability and a right to create art.

But this in itself belongs to an older, more noble tradition of the true artist who isn’t accepted by the prevailing art establishment during their own lifetime.

CFT: Yeah, that’s true.

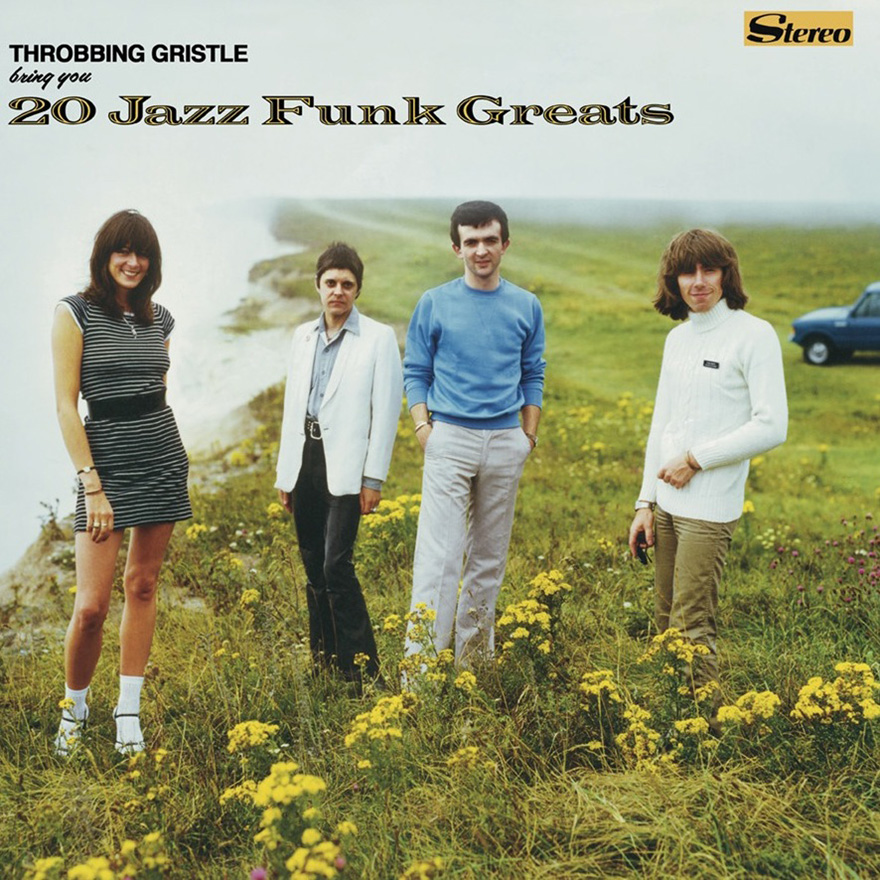

A person would have to be completely desensitized to not realize that they were being provoked by a lot of Throbbing Gristle artwork. But if you look at the packaging for the first two album–which seem to be poking at wounds in society in general–the leap to the cover art for 24 Jazz Funk Greats seems counter intuitive. Quite rightly, it’s now seen as an all-time great iconic piece of cover art, but at the time it must have come across like you were trying to goad your own fans almost.

CC: We were. You’ve hit the nail on the head.

What’s great about the new vinyl edition is getting to look at all the alternate photographs. It just reenforces how well thought out everything is, even down to the number plate on the Range Rover. So it’s organized down to the nth degree, but it’s still this really weird thing that doesn’t quite make sense.

CFT: That’s what’s great about coming up with an idea and then letting it roll. We said that we didn’t like the way that people followed us like fans. The whole idea was that people would go out and do something [interesting] themselves. But when it got to the point where people were arriving at the gigs wearing camouflage, we said we’d have to do something about it. Woolworths was still going then and they used to have a bargain bin for cut price albums. So we said we would make the album look like one of those albums you’d get out of a bargain bin in Woolworths. And so that’s where we took the initial idea for the sleeve and the title from. Because it was nothing like jazz funk and certainly not a greatest hits compilation. And then there was that nice kitsch photograph of us on the cliff top.

CC: That took a lot of organization and a lot of discussion about what exactly it should look like.

CFT: But that appealed to us because we’d never paid that much attention to something like that before and we said, “Oh, let’s treat it like a proper production, that will be really good fun.â€

CC: The whole thing became like a really big art production for TG.

CFT: It was a really fun day. Renting the Range Rover:

CC: Choosing our clothes.

CFT: It was like playtime for us.

Was the original picture going to be the one where you’re stood around the dead body in the heathers?

CC: No, that was just one of the other versions. We did about three or four different versions of that cover and we actually did use the naked body version for a completely different release. And we thought it wasn’t kitsch enough with the dead body.

CFT: It was too TG.

CC: It was too TG. We needed it to be less TG. We needed it to be just us stood on top of a cliff with other clues. The fact it was Beachy Head, a suicide point:

The reissue packaging shows some behind the scenes photos of TG, which reveals a more lighthearted side to the band. I’d never seen the Greatest Hits before and it’s great to see you all having a drink in a tiki bar with a plastic crab and a cornet, patently having a laugh. Did it frustrate you that people missed the sense of humor in TG?

CFT: It did and it didn’t. It didn’t bother me that much because we were just doing what we were doing and getting on with it.

CC: It did bother me.

CFT: Did it?

CC: Yeah.

For a lot of bands round that period, the most important thing was the studio artifact, but for TG, it was the live experience. I wanted to ask you about two notable gigs–one happy, the other less so. First of all, could you explain how you came to play to a bunch of schoolboys at a public school?

CFT: [Laughing] We got an invitation from Geoff Rushton (later John Balance of Coil), who got his music teacher to agree to let us come in and do a concert for the students. They were allowed to have a musician come in to their music class as part of their studies. He told his teacher that Throbbing Gristle were like John Cale. Sleazy, having been at boarding school and everything, was really up for it. We said great but we’d only come if we could make a day of it–come and have lunch with the boys and film around the building. So we did that and we had a fantastic day. And the gig was absolute mayhem, but wonderfully so.

CC: It was. We took Monte Cazazza with us as our support act and he wound the audience up before we went on. He was throwing things at them and they were throwing things back. So by the time we went on they were really up for it.

CFT: I remember looking out from the stage and there was a sea of public schoolboy faces and a balcony opposite where all the teachers were sat. And they looked like they were in shock. They were fixed to the spot. They couldn’t do anything. And then everyone started singing “Jerusalem.” [Laughs] That was such a wonderful moment. When they did that, I remember looking at Sleazy and we just beamed at each other: “This is great!â€

CC: It went from ‘Jerusalem’ to them chanting ‘Get your tits out’ at you.

CFT: And I was like, “No, you take your top off!†And one young kid took his rugby shirt off and threw it to me and it took all my strength not to let Sleazy take it off me. He wanted it desperately! But yeah, I kept it for a long time.

I guess the other gig I wanted to ask you about was the one where basically Genesis had taken an overdose of Mogadon. Did you have to stop the gig? Did it give you pause for thought? Did you think, “How far can we push this band before someone gets hurt?†Did you come close to splitting up?

CFT: Well, he took the overdose because I’d left him.

CC: He was very drunk.

CFT: I didn’t know he’d taken it. Because he used to get drunk at a lot of gigs and climb on the speakers: I remember looking at Sleazy and Chris and we were all looking at each other going, “Oh, here he goes again:â€, but this time it seemed a little bit more extreme than usual. But when we got home and said goodnight I got a call from Helen Chadwick who lived opposite us at the time saying she’d gone over there and called an ambulance, so you know: That’s what that was about though. It wasn’t about anything other than a relationship break up.

CC: It was a fantastic gig though.

CFT: It was a very good gig, yeah.

CFT: Like “Weeping”? Well he was a man who wrote that song, but also a man who was screwing whatever he saw at the time as well so you know:

CC: Double standards.

CFT: There were double standards going on at the time. It was a case of do as I say not as I do, with Gen and he crossed the point of no return with me.

Do you think now that Sleazy has passed on that you are beyond ever being able to sort your differences with him out?

CFT: Yeah. Nothing changed really. I don’t really think about him to be honest. It’s only when people ask me about him. I have no axe to grind with him, but I have no interest in him either. We have nothing in common. His morals are totally different to mine and I choose not to be involved with someone like that. It’s as simple as that.

That’s fair enough. When I listen to the first decade of Chris & Cosey, I feel that the difference between Heartbeat and Trance is a lot more marked than the difference between TG and Heartbeat, and I guess that I was wondering how you adapted to becoming a duo and if it was a process where it took you time to find your feet.

CFT: In a way we’d already started. In the studio in Martello Street before TG split up, Chris and Sleazy used to work on their own. I used to come down to the studio sometimes, so we were used to there just being two or three people in the studio working, so it wasn’t a huge leap to be honest. Also because when we did tracks like “Adrenalin” and “Hot on the Heels of Love,” we’d already started enjoying the construction of that kind of music and we wanted to take it a bit further. We’d not exhausted our interest in doing the TG hard-edged stuff but it had become second nature to us and it wasn’t as much of a challenge to us. We were ready to break loose and try something new.

CC: I guess Heartbeat was our crossover album. There were elements of that which we recorded while we were still in TG, so there’s bound to be some sort of influence there. But by the time we came to Trance we wanted to make a clean break and try something new.

CFT: And we’d moved on emotionally as well.

CC: We had yeah.

CFT: [Our son] Nick had been born by then. We weren’t here [in the countryside] at first–we were still in London until Nick was 2 and a half years old. We were still in London when the first album came out; I went back and did stripping for a while and Chris was like a house husband weren’t you?

CC: I was yeah.

CFT: We were living and working in a studio we had in Tottenham for a bit so it didn’t really change. Of course having a child changes your life but our focus was still on working and making music together. In fact when we were just starting to introduce Nick to solids I remember going to do the video for “Elemental Seven” and using his pram as a dolly for the video camera that we were using. So he was very much part of what we were doing. But we also had like a rule that we kept his routine going no matter what so he always had some stability as a child. In the evening, around about six o’clock, one of us would put him to bed. We had that rule.

Around this point, for whatever reasons, you turned down a tour support slot with Grace Jones and recorded some material with the Eurythmics. Did it feel that you were actually in danger of becoming accepted by the mainstream?

CC: Yeah.

CFT: Yeah. I was seven and a half months pregnant when the offer to tour with Grace Jones came through, so I couldn’t fly anywhere. That was the main reason why we turned it down.

CC: I think our careers would have been quite different if we had have taken that tour. I think it was Blancmange who took the slot instead of us. But working with the Eurythmics was quite interesting. I’m just sad we didn’t do more with them other than just one 12”.

CFT: But I think seeing what happened to them when “Sweet Dreams” hit No. 1 and her whole life got taken over it made me never want to go down that route.

CC: It really made us step back a bit.

CFT: I remember Geoff [Rushton] saying to me in the ’80s, “You can do all this stuff standing on your head. Why don’t you get out there and make yourself a fortune?” And I said, “I’m not interested.” I guess if we could be invisible and have someone else front it, then that would be a different matter.

But of course you have collaborated with a lot of well-known names. Do you take a radically different approach when you’re working with Erasure than you would working with Robert Wyatt?

CFT: Not really. You just take on what they are to you.

CC: And we have really different relationships with these people. Our relationship to Erasure is very different to our relationship with Robert. With Robert it’s more of a personal thing. All relationships are different and that affects how you work with them.

I want to wrap this up but first can you tell me anything about the Desertshore project?

CC: Just that we’ve recorded four tracks and we’re working our way through it very slowly but we’re very encouraged by what we’ve done so far.

CFT: It’s going really well.

And finally, when you look around at new music, do you see that pioneer spirit of TG and industrial music in anything new?

CFT: I think there is an undercurrent of the possibility of the pioneering spirit if you like. I’m waiting to see it in reality. I’m really hopeful to be honest. It would be really exciting to see it break through because I think it’s about time.