Photos by Hannah Jorgensen

At one of the first shows Loke Rahbek ever played, his then-band Womanhead opened for a Viennese saxophonist who also happened to be wearing a Darkthrone shirt. Even though this was Copenhagen—not far from where black-metal was born—Rahbek couldn’t quite wrap his head around the idea of a free-jazz player listening to “Kathaarian Life Code” and “The Pagan Winter” in his free time. That is until the Posh Isolation co-founder simply asked him.

“In a very fatherly manner,” Rahbek explains over email, “he patted me on the shoulder and told me that there were only two genres of music: good music and bad music. It is such an obvious statement today, but at the time it was what I needed to hear and had never heard anyone say before. That changed a lot of things for me.”

As simple as that story may sound, it very much forms the foundation of the label Rahbek launched with his Damien Dubrovnik bandmate (Christian Stadsgaard) five years ago. While that duo errs on the bleeding edge of performance art and experimental music—the last time we saw them play, Rahbek was dumping water on his head as if he was welcoming a public electrocution—the music they release on strictly limited tapes and 12-inches cuts across a wide swatch of ambient electronics, noise, punk and synth-pop. It’s also provided a public record of the underground Copenhagen scene they helped shape—one that revolves around the performance/rehearsal space Mayhem and bands like Iceage, Lower, and Lust For Youth, which Rahbek officially joined recently. (He co-wrote some of the material on International—an album due out through Sacred Bones on June 10th—and has also played with members of Iceage and Lower in side projects such as Sexdrome, Vår and Croatian Amor.)

We’ll get to how all these close-knit friends cross over conceptually in an extensive Copenhagen package this summer (via our free iPad app); for now, here is where it all started in many ways…

Tracklisting:

Mischa Pavlovski – “3” (Kapitel LP, upcoming)

Croatian Amor – “Generations” (The World LP, 2013)

Marching Church – “I’m Not Worthy” (“Throughout the Borders” 7”, 2013)

Rosen & Spyddet – “Vægten og Timeglasset” (Springet som Symbol tape, 2014)

Sand Circles – “Continuity” (Rosehip, Scallop, Dancer compilation, 2013)

Olymphia – Transistion (Entrance tape, 2012)

Communions – “You Go On” (“Cobblestones” 7”, 2014)

Age Coin – “Knees Knock Together” (Rosehip, Scallop, Dancer)

White Void – “Some Days are Better Than Others” (“We’re Falling” 12”, upcoming)

Puce Mary – “Unnatrual Practices” (Success LP, 2013)

Vanessa Amara – “Untitled” (Both of Us / King Machine LP, upcoming)

What’s your earliest memory of connecting to music on a deeper level? Did any particular artist or album help you realize that there’s no such thing as ‘noise music’, that ‘noise’ is an attitude and sense of artistic freedom more than anything else?

Loke Rahbek: My father was responsible for most of my early music upbringing. He gave me his record player when I was about 11 and his collection that consisted of records ranging from Michael Jackson to the Cure, to Danish punk, to Talking Heads and Brian Eno. Besides that, my entire family on my mother’s side are classically trained musicians. My first experience with ”abstract” music of any kind must be Brian Eno’s Music For Airports. That’s still a big inspiration for me today.

Christian Stadsgaard: It’s almost a cliche, but for me, it was the Smiths. I was in seventh grade and right in the middle of puberty and very drunk with teenage angst. That was the first time I realized that music could be more than just entertainment. The first time I realized that noise could be music was while listening to Merzbow. The way all these frequencies blended together in interference, the abrupt dynamics and the potency of the music, I thought it was absolute genius.

http://youtu.be/RfKcu_ze-60

http://youtu.be/dJVaxD8GDWw

How about art in general? Do you remember visiting a gallery or exhibition that made you look at the world in a different way at an early age?

Christian: I remember seeing a retrospective Fluxus exhibition at a young age that really blew my mind; I realized that that could be art. I can’t remember ever being as excited about an art show as that first introduction to Fluxus.

How would you describe the music scene you grew up around and how it’s changed as you’ve gotten older and become an active participant in every aspect of it?

Loke: I never had any musical ambitions as a child. I remember my friends at age 10-13—starting bands, dreaming about “rock and roll”— and O always found it silly and uninteresting. It was not ’til age 15-16, when I saw my first noise performance at the opening of a small art show I was taking part in with some friends of mine. One of the other people in the exhibition had invited his friend to perform and the 15-minute weird noise spectacle made a huge impression on me. I spoke to the performer after the show and he invited me to a show he was hosting the next day in a small underground art space in Copenhagen. I went there on my own—none of my friends at the time were interested in going—and the first night I met Christian, who was co-hosting the show. I started going to as many events as I could, and thanks to Christian and the performer, Anders, I got to see many beautiful events over the next few years.

“It is a matter of focus—about holding your head in a different way, allowing you to see more of the sky and a bit less of people’s feet”

Not long into that process, I convinced my classmate at the time, Alexander Fnug, to start a band with me. He knew how to play guitar. He was confused at first—why did I want to start a band when I did not know how to play any instruments, and clearly had no intention of learning? We ended up forming Womanhead, which in some way later turned into Sexdrome with Bo Høyer and Anton Rothstein. Before that happened we played improvised and highly unusual and often very messy concerts as Womanhead for years. When Christian and I started Posh Isolation years later, there was still hardly anything that would qualify as a scene and the first idea of starting a label came from the wish to put out our own music. The Copenhagen of today is a very different thing.

Many people—especially Americans—group Norway, Denmark and Sweden together as if they’re all the same country. Which is ridiculous of course. What are some distinct differences between Denmark and your Scandinavian neighbors, both culturally and creatively?

Loke: Americans do a lot of strange things. Norway and Sweden do not have Posh Isolation. Technically a few Swedish people do.

How do you relate to Copenhagen as a whole? Do you feel like an outlier most of the time?

Loke: Copenhagen is the base of Posh Isolation; it is also the city I have lived in my entire life. I feel at home there, our friends are there, the people we work with are there. The man that sells me coffee knows my name, and the girls that own the clothing store next to our shop smile to me when I meet them in the morning.

When did you start feeling a responsibility to present the music/art around you via your own label?

Loke: We started the label to put out our own music. There was no one in Denmark doing this thing, and there was definitely no one interested in putting out releases like this. So we decided to do it ourselves. At first it wasn’t so much done out of responsibility, but it was obvious that if you wanted something to happen you had to start it and not wait around for other people to come and design the entertainment for you. I had been organizing very small scale art shows and had been putting out zines already, and Christian had been putting up experimental music shows for half a decade and already had some experience with running an underground label from earlier. It was the obvious choice and the pairing proved to work.

You once told The Quietus “the artists we appreciate and work with make art not to change the world, but to make a new one.” What does this new world sound and look like?

Loke: It is in the work, it is there for everyone to look at and to listen to. If we could sum that up in a few sentences in an interview, there would hardly be any point in spending every waking hour working with this architecture. The thing about these worlds is that it changes as well, in many ways much like the real world. It never stays the same for very long at the time. It is our assignment to keep it up.

Do you even view Posh Isolation as a label, or do you look at it as more of an abstract entity that provides a home and a purpose for the art you create?

Loke: Of course a large part of the operation of Posh Isolation is “label work”—handling a mail order, talking to pressing plants, folding covers, dubbing tapes, writing endless amounts of emails—but at the same time, I think it is something different. When I meet people running “real” record labels, I find I most often have very little in common with them. I guess it is a matter of focus—about holding your head in a different way, allowing you to see more of the sky and a bit less of people’s feet.

To me, Posh Isolation is a study of language. We look at the releases as invitations in to these aforementioned “worlds”, or rooms, for a less dramatic word. In order to make the invitations work you need to have a firm understanding of your language and the different dialects the different artists of the label speak. We used the metaphor of a house before, where every release is another brick that both adds to the this architecture we are trying to build and at the same time is its own thing. That is why we also knew from the beginning that we would never involve people with the label that we didn’t personally know. It is not that kind of project; that is not our role to do.

Christian: I think for the both of us Posh Isolation is more than a label. It may sound a bit dramatic, but I think both of us see it as an entire identity. It’s a way we deal with the world and a way to approach almost anything within in. So I would say its some more than music and art; it’s a way of life.

http://youtu.be/StcFZJRZ8HE

How did you two meet? What led to you working together as Damien Dubrovnik and how did you end up meeting the other people you’ve worked with closely—people like Elias from Iceage, Puce Mary, etc.? Is the underground Copenhagen scene simply a small, close knit one, where everyone quickly gets to know everyone else and support one another?

Loke: It was timing. I think that if you need something and you start looking, it will eventually come to you. Both me and Christian needed something new and someone new to do that with. The first record we made and which was what started posh isolation, we recorded over the course of a month in his studio while getting to know each other. We never talked about what we were going to do. We went in and did something and the result was something that none of us had heard before or imagined. I don’t fool myself to think of that record as particularly masterful in anyway, but it was an introduction to something for the both of us. It was the appearance of new language, and that is ultimately what this is about and have been about ever since. Everyone else came along the way—some found us, some we found, all in different and yet similar ways. It is the eagerness to learn and to experiment that ties all these people together, and that is the foundation. There is no place in the world I have visited that has what Copenhagen has.

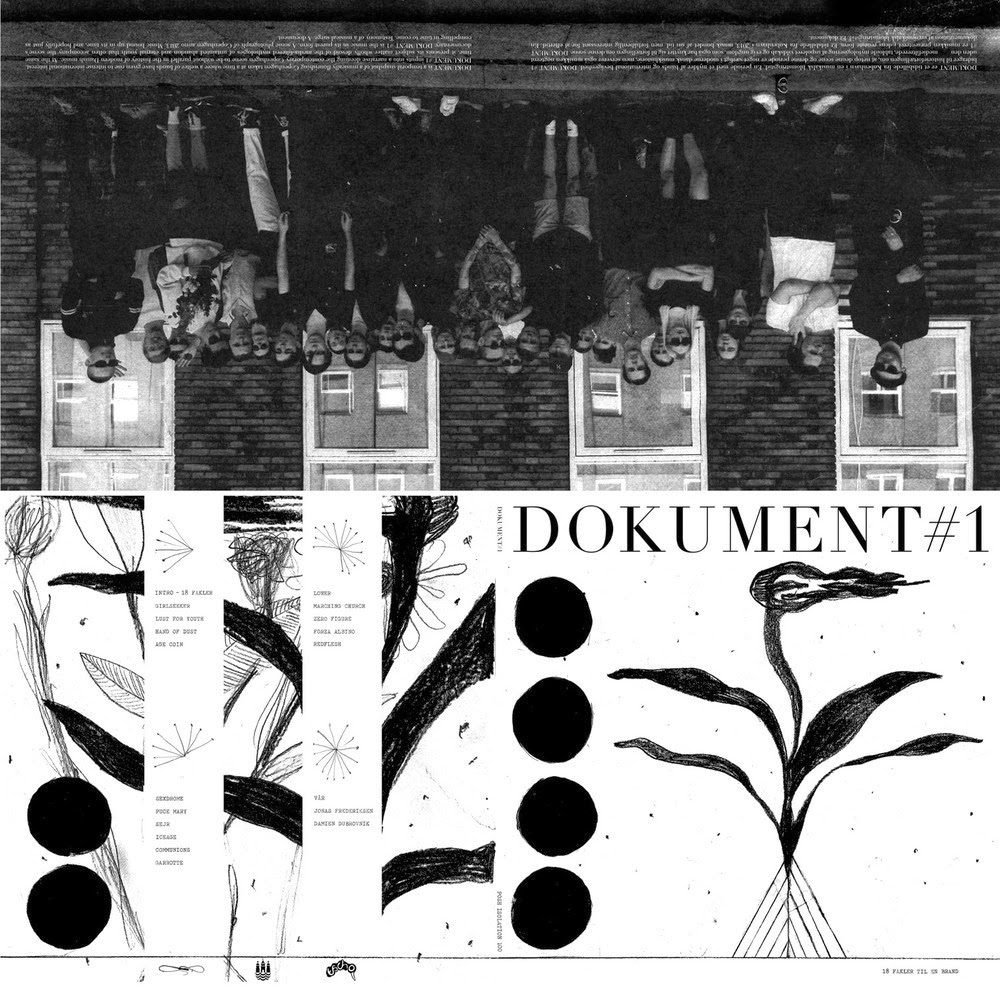

One thing people in the states don’t realize is how overlooked some of your music is back home. Given that, you must have been excited about level of awareness raised by the Dokument #1 project the Copenhagen Main Library produced late last year.

Christian: We started out within the infrastructure of noise music. That means we aimed at the international scene for that kind of music, and had no interest in local media, as that had no interest in what we were doing. At some point the music department in the Copenhagen Library approached us with the project, as they found it odd, that a scene in Copenhagen could draw that much international attention, but zero national.

Tell us a little bit about Mayhem, the space that houses many Posh Isolation projects and has become a center of your scene in many ways.

Loke: Mayhem was founded a few years after Posh Isolation by Johs Lunds and Sune TB Nielsen, quickly joined by Tobias Kirstein, with the idea to create a venue or performance space for experimental music, to avoid the compromises of dealing with “regular” venues. At Mayhem you don’t have to explain yourself. There is no sound guy to tell you that the feedback is not supposed to be there or that the decibel is above whatever level is set for that sort of thing. It is a place to experiment; it is also the home for a large part of the names of Posh Isolation. The building consists of a room for events, and a 6-9 rehearsal spaces and two toilets. Puce Mary, Age Coin, Damien Dubrovnik, Lust For Youth, LR, Communions, Hand of Dust, Vår, Iceage, Lower, Skurv, Girlseeker, Forza Albino, Sejr, Marching Church, Croatian Amor and many more. We all work there. Some rooms are shared, some are just next to each other.

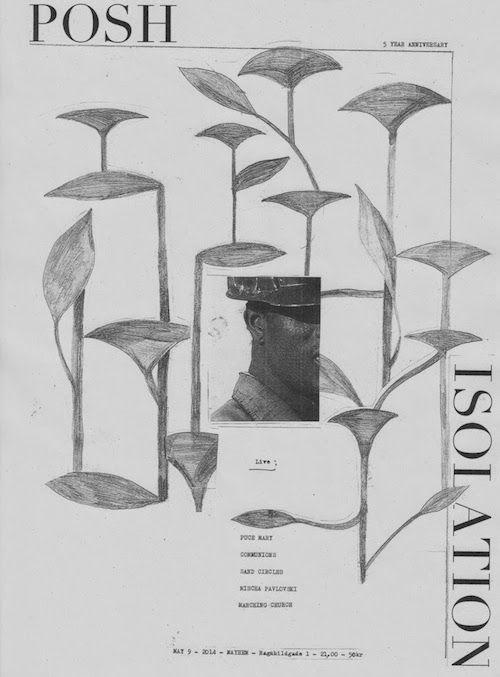

You celebrated your fifth anniversary there recently. How did it go? Is the label where you’d hoped it be after five years? Where do you hope to be with it five years from now?

Loke: The five year celebration was a beautiful event. It was at Mayhem and in that aspect, it was very much like it has always been. Only more and better than it ever has been before; there were five beautiful shows and a dance party.

We are happy with where the label has gotten these first five years, but there is so much to do, so much to learn and so many things to get better at. Lets see how deep the rabbit hole takes us.

Posh Isolation’s releases are really limited and hard to track down, especially here in the states. Let’s say someone is new to the label and wants a solid introduction the range of sounds you represent. What are five records they should start with and why?

Loke: That is an impossible question; everything put out was put out for a reason. They all in some way or another interact with the release before and after them. I would say pick any five, roll a dice and if nothing speaks to you out of those five, chances are the other 125 won’t either. Or pick from a title or a cover. That is what I usually do: always judge the book on its cover.

What role do you think Posh Isolation plays in modern Scandinavian music? How do you hope to fit into its future?

Loke: I think we have presented some of the finest visual and cultural phenomenons that has seen the light of day the last five years and we have worn our shirts nicer than most, and I think and hope we will continue to do both.

Christian: Copenhagen was never on the map of experimental music before Posh Isolation. Maybe some electronica drew some attention in the ’90s, but never before has there been such a clear expression of will and creativity coming out of Copenhagen. So obviously the infrastructure of Scandinavia has changed in that sense. We hope to be able develop the label as much as possible and keep the energy within the group of people we work with boiling.

How do you feel about the art exhibition (Contaminate) you put together last year? Do you have any other gallery opportunities coming up in 2014?

Loke: Contaminate was like an exam. It was a chance to see these aforementioned “rooms” translated into physical, four wall, white cubes, to see if the language of Posh Isolation could be translated in a way that it would make sense in the institutionalized art world. To us it was a huge success and a personal victory. There is a lot more to be done in rooms like that; we will see when the next event of that sort will be; it is too early to say.