Photo by Pablo Van Winkle

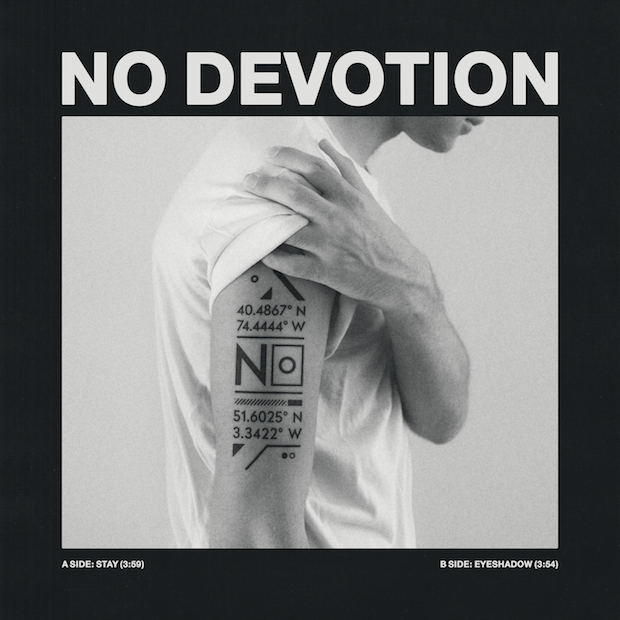

Geoff Rickly sure is sneaky. Heading into our interview on Monday morning, we knew a few things; namely that the former Thursday singer would soon be rebooting his Collect Records imprint with a proper staff, stacked release schedule, and a highly publicized premiere on BBC Radio 1’s Rock Show Monday night. When we guessed that the premiere had something to do with No Devotion—the band former Lostprophets members formed after their singer was sentenced to 35 years for numerous sex crimes against children—Rickly admitted we were right but left out one key detail: He’s their lead singer. Which is strange on several levels, beginning with the simple fact that Rickly was never a Lostprophets fan. Not even a little bit.

“[Their manager] Karen [Ruttner] tried to get me to listen to the [No Devotion] demoes five or six times,” explained Rickly, “but once I heard them, I was like, ‘Holy shit. Why have you been hiding this side of what you’ve been doing forever?’ I think they’re gonna lose some fans because of it because it’s not another Lostprophets band with another troubled person singing. They’re just gonna be like, ‘Where’s the mosh?'”

Why, it’s smack dab in the middle of Rickly’s other imminent release: The Next Four Years, a high concept hardcore record from United Nations best experienced as a box set. That way their screeching manifesto is viewed the way it’s meant to be heard: as several stages of the group’s semi-fictitious career, which started as a loosely aligned supergroup (including members of Converge and Glassjaw at one point) and recently evolved into the most acclaimed project Rickly has been involved with since Thursday split up three years ago.

So life is… complicated. And we discuss it all in detail below…

So you must be psyched; today is a big day for you.

Today is a crazy day for me, yeah.

What’s with the massive rollout for the label? Is that something you’ve been working on over the past year?

Exactly. At the beginning of this year, it got a lot more serious. I was able to start hiring a staff, and now we have Norman [Brannon] from Texas is the Reason as our manager, doing a lot of the creative decisions, and we have Shaun [Durkan] from that band Weekend as our in-house creative. He designs record ads—all kinds of stuff like that—and we also have Leonor, our office manager. So yeah, we’re planning on doing a bunch of releases in the next year, and today is kinda step one.

What’s it like being the boss now?

Well I’m the owner, so you could say that, but really we’re all just working together on the same goal. I don’t think of myself as the boss. Norman has more of a grasp on getting things done, and most of the time, will tell me things I need to do [laughs].

Was Norman a manager before then?

Yeah, he managed a dance label, and he has extensive experience working with labels, whether it was Revelation or Jade Tree for different things.

What was the dance label he worked at?

Primal Records.

“In the next few years, I hope I have a chance to do things I’m even prouder of than Thursday or United Nations”

Was the decision to work mostly with musicians intentional?

It was part of the design, yeah. One of the things musicians find frustrating with their label is when they’re like, ‘You guys just go out and do your thing on the road. We’ll do all the important stuff back here.’ And you’re just like, ‘What are they doing? Go out on the road? You get to go home to your house every night and we’re out here in a parking lot in Utah.’ You know what I mean? So it was really important for me to put together a team of mostly musicians who have toured and know how important it is to have posters up at a venue before you play it, that sort of thing. We want to have a physical presence—in stores and on the streets.

You want to be really hands on then?

Yeah. I had released a few records before we really launched Collect, like the first Touché Amoré with 6131, Midnight Masses with Conor [Oberst] from Bright Eyes on Team Love, and the first United Nations with Eyeball. But I wasn’t really working the records. I was pressing them and putting them out. At one point, I realized that was more hurtful than helpful. Like, ‘Great, I gave you guys a boat, now go out on the ocean and have fun!’ Never mind the waves or the lack of a coast guard.

Did you want to do a full-time label ultimately, or did that decision happen later on?

I never thought I wanted to do a label full-time. I was the one from Thursday who argued against self-releasing because I was like, ‘Man, labels who still have staffs, we can’t do that ourselves. These people know what they’re doing. I actually have respect for them.’ They have a harder job every year but they can still be worthwhile.

I’m also getting older, so I want to settle [down]—spend more time with my girl, think about kids, stuff like that. I also realized I never wanted to stop being a part of fostering art. In the next few years, I hope I have a chance to do things I’m even prouder of than Thursday or United Nations.

Are you planning on releasing your own projects through the label too then?

Oh yeah; eventually I will. United Nations and Temporary Residence wanted to work together for years, so I didn’t want to be like, ‘Now that I have a label, screw you.’ I love [Temporary Residence founder] Jeremy [DeVine]; I ask him every day what I should be doing with my label.

With United Nations, you seem to be working with a bunch of ex-hardcore kids.

Yeah [laughs].

So it’s a nostalgia trip for everybody.

Exactly. And even though we know they’re all hardcore kids over there [at Temporary Residence], they’re known for being more of an art label that does a lot of instrumental stuff, or William Basinski. So we’re rephrasing it [for fans of the label] like, ‘Oh sure, it sounds like noise to you, but if you give it a further look, there’s a lot behind it, right down to all the artists we work with.’

Let’s talk about the evolution of United Nations. It started as more of a satirical project and seems to have evolved into something more serious. What does it mean to you at this moment in time?

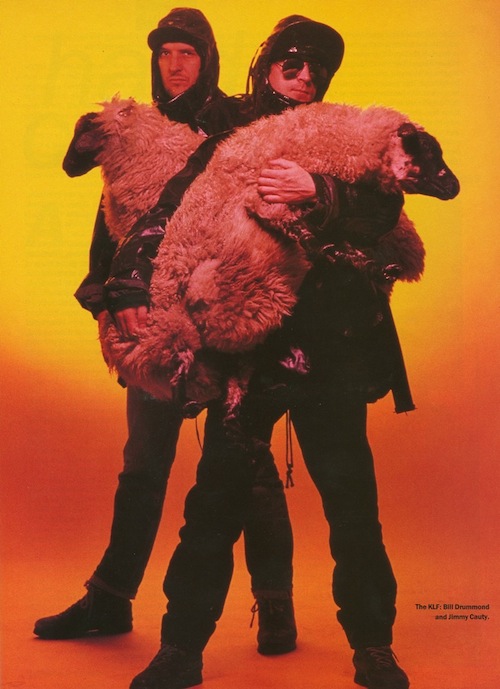

The first idea was to be a Gravity Records kind of band, like, ‘We should just sound like Orchid or Reversal of Man, and that’s it.’ And once we started working on it the first time, I was talking to James Cauty from the KLF… He did the art for the first record and was like, ‘You know, this is going to get banned, and you’re going to get sued, so if anybody asks, I’m going to say you stole the images from me.’ I was like, ‘Well that’s pretty punk. I like that.’

We were also talking about reading The Illuminatus! Trilogy as kids. It’s kinda a satire of politics, conspiracy theories, and how ridiculous the whole thing is. So we talked about putting out the most political record that actually has no message. Like none; it’s just folding in on itself, a joke of a joke of a joke. That’s what the first record was. And when we got to Never Mind the Bombings…, we wrote four songs we were actually really proud of, and got another great artist, Ben Frost, to do the cover. It was still satirical, but it was also a little more serious and trying to say a few things, trying to criticize punk culture for being as capitalistic as everything it pretends to be against. It’s just as much about ‘coming to buy our T-shirts’ as anything else.

This record is more developed and mature because we decided that the best form of critique isn’t political or punk critique; it’s critiquing ourselves. So the record is a lot more personal—a lists of all the ways we’ve failed all the things we once believed in, and accepting the status quo of how band things have gotten. It’s sort of examining our own level of privilege. The box set is supposed to be a fake mythology of the band. The cassette is the first demo—the band at its most basic—then there’s the two 7-inches, and the 10-inch is where we get into our pretentious phase of trying to sound like Godspeed [You! Black Emperor]… Depending on the groove you land on, it has two different endings. It’s like a fork in the road, and the needle ends up in one or the other.

The record still sounds cohesive though. Like there’s a logical progression to it.

Oh, that’s cool.

That’s not intentional then?

It’s kinda accidental because we decided we were better in small doses before we did this record. It’s way easier to digest; as a full-length, it gets a little grating and monotonous. We do one thing, and we have no qualms about that. We may do it two different ways, but it still ends up being the same thing. You know what I mean? [Laughs] So this is our chance to say, ‘Listen to these two songs. Now listen to these three songs. Now listen to these four songs.’

Couldn’t someone listening to it on, say, Spotify miss that context entirely?

Yeah, I mean, that stuff to me is really central to what we’re doing. Because each 7-inch is a different scene, especially the second 7-inch. It’s meant to be played at 33 and 45 [RPM]. One is blast beats and the other sounds like a doom record. It’s about United Nations finding god, this idea that you can put anything in between two mirrors and it will reflect to infinity. You could decide its god, money or yourself. As far as it being important to me, I think the box set is the only way to get it right.

Developing the storyline to that degree certainly took a lot of devotion.

[Laughs] Yeah, we’ve been joking around nonstop about the Vice love and the Best New Music on Pitchfork because we set this up to not be a career band.

What have been some other misconceptions about this band from the beginning then? It seems like there’s been a series of them, really.

One of the misconceptions is that getting sued by the United Nations was a prank too. But that was real; it totally screwed us for a while. And we haven’t really resolved it. We’re just hoping they don’t care anymore. That’s our strategy: Maybe they forgot [laughs].

“We’re not trying to be Banksy; everyone knows who is in this band”

Did the United Nations thing freak you out a bit then? Or was it just really weird?

It reminded me of being bullied. Ever since I was a kid, I always hated being bullied. I have a pretty formative memory of being bullied for years and years, then finally snapping and beating the shit out of the kid who bullied me. Ever since then, I always had this thing that the best thing you can do when someone is messing with you is to mess with them. Whether that’s smart or not, that’s been my reaction to it. No matter how you look at it, it’s art. There’s no way of mistaking us for a humanitarian organization. We haven’t gotten a letter from a refugee asking for our help, you know? We’ll never be big enough to pose a problem, so at the very worst, they’ll convince us we have to stop doing this, and then it’ll be done.

Are you looking to make this more of a full-time thing in the interim?

Everybody is pretty excited about the idea of doing it more often. That being said, we’ve always been a band with members in other bands. And I’ve got a full-time job now with my label too. But if we can hit other countries because people are loving it, that’d be awesome. I don’t think it’ll ever be a full-time band, though.

A big part of this project has been everyone but you remaining relatively anonymous. How much of that is legal issues and how much of it is intentional?

It started as a contract thing in the very beginning. And once we worked out this whole thing with the silly Reagan masks, we thought we might as well keep it that way. Then we talked to people like James Cauty and thought, ‘You know, let’s not copyright these songs. Let’s let anyone who wants to cover them, cover them. And anyone who wants to sample them, sample them. All this art should be really free. Why even put it in our name?’ We’re not trying to be Banksy though; everyone knows who is in this band. We’re trying to make it for the people, of the people. It’s not about ownership or us making money off the publishing. It’s just out there.

This record is the same situation then? You didn’t copyright anything or set up your publishing?

We haven’t. It’s something I wanted to discuss with Jeremy, because I don’t want anyone to bootleg his records. He works too hard for that. There may be a way to control the record without administering the publishing. Because there are different levels of copyright law.

Now that you have your own label, what’s your perspective on how the industry still seems to be fighting a battle they can’t win, whether it’s by taking a YouTube video down or flagging a Soundcloud track they didn’t clear? Doesn’t it seem like all of this is free promotion in the end, and that a lot of this stuff is going to get out there, no matter what you do?

Fighting it is a losing battle, yeah; you’re not going to stop it. And honestly, people are always a step ahead. You see that even in how war campaigns are led. The guerrilla stuff beats the concerted efforts. It’s just the way it is. So while I don’t think it’s cool that people don’t even think about paying for records anymore, I’d rather use it to our advantage than fight a losing battle, even if it’s just used to sell concert tickets or T-shirts. Ultimately, that’s what our company is about—helping the artist, not just selling a piece of plastic that has music on it. You have to go with the tide of the times, you know what I mean?

What’s your approach business wise then?

One of the big things we keep saying is whenever we can, it’s not even Collect Records; it’s just Collect. Because it’s a creative company, not just a music one. We’re helping artists sell great art. We’re not sure how we’re going to monetize that yet. We’re starting by selling records but the company has to be bigger than that. Otherwise, it’s just another label, which I’d be pretty bored by. It’d be pretentious to say we figured anything out but we’re looking to do something more. And to be realist about it, we can’t think, ‘Well, they’ll fix this downloading thing soon.’ I’ve heard people say that at meetings. When [Thursday] were on a major label, someone said that he had it on good authority that this whole downloading thing was going to be done very soon.

And who did he hear this from?

He said he sat down with the RIAA and they had it figured out. I was like, ‘Awesome, good job’ [laughs].

Going back to your relationship with James Cauty, how did you track him down? I was under the impression that the KLF were hard to get a hold of.

Well, early on in Thursday, I didn’t know what to do with my savings, and at one point, a friend gave me some art from our contemporaries. Then Shepard Fairey designed a Thursday logo, so I got some of his art. I had met Banksy early on, too, so I had some prints of his. The same with Yoshitomo Nara. So I decided to use my savings to collect art. And then if I ever needed to, I could sell some art.

I started collecting James Cauty’s work because I was really fascinated by the KLF book, and the whole idea of anybody can have a hit. I noticed after a time that he was literally sending [his art] out by hand. So I decided to write him, as a collector and a friend. At one point, Thursday was touring in England, and I said I’d love to buy him coffee. He asked me to come by his art studio and so I went by, and we just started about stuff. It was great. I find that visual artists don’t get the hype musicians get, so if you reach out in a direct and sincere way, most of them will at least talk to you. That’s been a really cool thing for me over the years.

James Cauty has been mythologized in some circles. How did meeting him compare to people’s preconceptions?

It was cool, man. Obviously there’s some kind of Thomas Pynchon thing, where you always want it to be a mystery that’ll never be revealed but he’s just a normal human being. His art studio is amazing, and his views are very much intact. Like he was like, ‘I’m not going to give this to you if you’re just another stupid fucking band.’ And I was like, ‘Well, we’re not a band. We’re more of an idea.’ He was kinda down with that, and he was into the fact that we were willing to be sued by the Beatles. Which never happened; we got sued by the United Nations first.

You must have assumed that cover was going to be banned when you had it made though.

Right, but we didn’t see it coming from the United Nations. We had a backup pressing for when the Beatles cover got banned but that never happened. We had our guard up on one side and the punches came from another.

Going back to this art collecting thing, that’s a pretty mature business move to do when you’re young.

I wish my first wife thought that [laughs]. She was more like, ‘What are you doing?’ ‘I don’t know; I’m buying art.’

Your timing was decent too. It sounds like you got a lot of this stuff before it was too expensive.

Yeah. Even stuff like Ray Caesar—I got him before he was a big artist. I had a Mark Ryden but I gave it to my wife when we split up. We just got an original from a great graffiti artist from Chicago called POSE and put it on our wall. It’s really cool, especially when you get to be friends with some of them and they’re already fans of the band. It’s a very nice mutual respect.

What was the first major purchase you made then?

I went from collecting stuff to being serious about it when a friend gave me a Yoshitomo Nara piece. I realized he was such an important voice in Japanese culture—that you can’t even get prices for his stuff until after they run a credit check on you—and his work was pretty valuable. Then I started to look at things like, ‘Well, if I have a double of this print, I can sell it to get something from this young artist who I really think is going somewhere.’ I try not to be too speculative though; if I know an artist is going somewhere but I don’t like their work, I’m not going to buy it.

How many pieces do you have right now then?

If you count prints, about 60 or 70.

Have you sat on everything you have, or have you sold some stuff?

I’ve sold some stuff. After Thursday stopped and before I figured anything else out, I sold a Banksy piece for a good amount of money and a couple other things.

“When we were building the label, I wanted to be a young 4AD. That’s the dream to me.”

How did you end up with a Banksy piece?

He was friends with Shepard [Fairey] but his stuff wasn’t super crazy expensive yet. He was just this sorta weird guy starting to cause some trouble in England. Believe it or not, he was painting the wall in the G-Star store in Soho back then. I don’t know if it was a Banksy piece or he was just earning extra money by painting the wall but that’s when I got the first thing I got from him.

Considering all of this and the name of your label, I assume you’ve always been into collecting stuff?

Yeah. When I was a kid, it was comic books. Then when I got into literature, I started collecting first editions like Underworld by Don DeLillo and other stuff from that period. Flippant collecting—where it’s just about collecting the most valuable piece—that doesn’t really interest me. In today’s disposable culture, it means something to actually have something in your hands and want to put it on a record player and listen to it. That kind of value is a little more rare—where someone’s actually committed to it. I’d like to foster that with what we’re doing, where people actually love what they got.

So are you looking to push some boundaries with your packaging?

Probably at some point. For now, it was really important to get some great artists involved and make everything look nice. Not super high price, but everything release is super beautiful, and we spent a lot of time on the branding and the logo.

Is Shaun going to do all the layouts to maintain a certain aesthetic then? Like early 4AD or something like that?

Shaun’s not going to do every record but we have a couple systems in place that’ll carry over to every release and give them an archival quality. It’s funny that you mention 4AD, because when we were building the label, I wanted to be a young 4AD. That’s the dream to me. They’re kinda in a classics phase right now; I want to be where they were when they first put out a Cocteau Twins record—just trying to make it work and find cool stuff.

Can you tell us about your initial signings?

Black Clouds is a three-piece instrumental band from DC. They’re sorta a doom-y, metal-y band but they made this record that’s gorgeous. It’s called Dreamcation, and it’s really beautiful.

Dreamcation huh?

[Laughs] Yeah. It sorta floats and smashes alternately, but it’s always pretty. I know the guys in that band Mono are obsessed with Black Clouds right now.

It sounds like they’ll be touring with Deafheaven in no time.

Maybe [laughs]. I know those guys are buddies, so we’ll see. The next band is Vanishing Life, which is some guys from …Trail of Dead and Walter [Schreifels] from Quicksand singing. That’s a really great older guy’s punk band.

Who’s in it from …Trail of Dead then?

It’s Autry [Fulbright II], Jamie [Miller] and I think Jason [Reece] is going to be in it sometimes. It’s going to be a little bit of a rotation, I think, although I may be a little bit wrong about that because Autry’s kinda in charge over there. So it’s not Conrad, which makes sense since Walter is in that [frontman] role.

Walter’s career has evolved quite a bit over the years, so how does this fit into his general evolution as a songwriter and performer?

I think he sees bands like Fucked Up, Iceage and Off! making hardcore records he likes and since he’s been moving away from hardcore since Rival Schools, he kinda wants to make a hardcore record that’s more like what he’d like now as an adult. He’s not stopping his solo stuff; he’s just looking to make hardcore that interests him now.

So all of us who grew up with Quicksand should be pretty excited about it?

I mean, I am. I am kinda freaking out about it, because they were obviously a giant influence on Thursday. Sick Feeling just gave us the mix of their full-length. We’re doing that with Terrible Records. It’s one of the things I’m the most excited about because Don [Devore] from Ink & Dagger is kinda brilliant.

Oh Don’s in it?

Yeah, it’s Don’s band, and then Jesse [Miller-Gordon]—who tour manages Mykki Blanco, Death Grips and all these other hip-hop groups—he’s the singer, this little wise ass jerk, which makes him the perfect hardcore frontman. I’ll be like, ‘Do you like this thing?’ And he’ll be like, ‘No, but Don hates it, and I love making Don hurt, so I love it.’

Does he even have any experience as a musician?

No. He’s like, ‘I love hardcore; I’m going to try it.’ But he’s actually a great writer; his lyrics are fantastic. I can’t wait for people to read them. They’re really simple but when you read them, you realize they’re pretty powerful. But yeah, that’s got a noisy, My Bloody Valentine, hardcore kind of thing. That’s a kinda overblown statement to say, and it sounds like it’d be pretty but it’s not. It’s psychedelic and heavy.

How did you end up working with [Terrible co-founder] Ethan [Silverman] on that?

He was into doing the record before I started doing Collect but I was living with Don at the time. So as soon as Collect got together, we talked about doing it because he worked on my solo stuff and I did some things with Ink & Dagger before. I can’t wait for you to hear that record—it’s really abrasive but really cool.

So I’m guessing the last, secret project you’re announcing later is this Lostprophets thing you mentioned putting out before.

Yeah, and that’s going to be the most shocking one for people. Because it’s kinda got this great, moody, dreamy thing to it no one would expect from the Lostprophets guys. I wasn’t a fan of their band that much but what they’re doing now is really great. The track in particular that they’re debuting tonight is very Jesus & Mary Chain, with a little Cure, a little Chromatics. There’s a lot of cool stuff mixed in there.

Considering you weren’t into their last band, how did they get in touch with you in the first place?

Because their manager Karen [Ruttner] is a really old friend from New York. She used to DJ with Sarah Lewitinn, and she was doing stuff with the Horrors for a little while, and Idlewild, and Lostprophets. Which surprised everyone because she was into such hipster stuff. It’s like, ‘What are you doing with Lostprophets?’, you know? Anyway, a friend of mine runs Mission Chinese, so I said we should get something to eat there and that I wanted to know the inside story on everything [around their breakup and the indictment of their singer].

After a while, I realized that Stu [Richardson] and Mike [Lewis] are old friends of mine. I was like, ‘Oh god, that’s so horrible. How are they doing? Are they okay?’ And she was like, ‘No they’re a wreck.’ For the first year, they didn’t believe any of the charges. They thought it was a vindictive ex-lover of his because ‘he’s an asshole anyway.’ But when he pled guilty to horrible things none of us ever knew it was a shock for those guys. I thought they were all gonna quit music for good overnight. So I was proud of them that they stuck with it, went to counseling and did some stuff to see it through to the other side.

In terms of how [No Devotion] sounds, did those guys tell you this is the kind of music they wanted to write all along?

Exactly. They would write some of these songs and say, ‘What do you think? It’s a little different for us.’ And [Lostprophets singer] Ian [Watkins] would just be like, ‘No.’ So they were resigned to finding a project for it someday. But yeah, it’s noir but ’80s; it’s interesting. I really love it.

You must have viewed Lostprophets as a band that got thrown together with Thursday for the wrong reasons.

In the UK, we did, and I was always like, ‘Fuck that, Thursday’s doing cool shit, and they’re not.’

Now that a few years have passed, how do you feel about how Thursday ended, and what did you learn from that experience that you’d like to apply to your current projects and label?

It was so abrupt man; after 15 years, it was just so abrupt, so hard. Now that I have some distance from it, I sorta regret how it ended. But I generally feel like No Devolución should be our last record. It’s tied with Full Collapse as my favorite thing we ever did. I think it was the strongest. It had a statement. It knew what it wanted to be—this is it, take it or leave it.

So I guess my biggest reflection from that band is that we were actually good. Even though we were the most hyped band for a minute, we had a backlash when everyone was like, ‘Fuck all those bands.’ I look back and think, ‘Fuck that. We were good. I don’t care what anybody says.’ Although we’re kinda becoming cool again, with Deafheaven and other people dropping our name. I don’t care either way though. I love that band, and I love that time.

Were those shows where you played Full Collapse again hard for you?

It was never hard; it was really awesome that people still loved those songs after 10 years.

Was the band nearly its end then though?

No, believe it or not, it was a three-day thing. We were planning tours, and something we never disclosed happened between members of the band. We thought we had to be done, so we announced it the next day. We would have done it even earlier but Thrice broke up that day and we wanted to let them have their moment. We didn’t want to flood the internet with both of us breaking up in the same day. But yeah, from the time we knew we were going to break up until when we actually did, that was three days.

You must not have been able to process anything then.

Oh yeah. I was in a different country, and something happened back home, so I found out the band is basically done. I rushed home and said, ‘So is the band over?’ And everyone was like, ‘Yep.’ ‘Okay, I’ll work on an announcement.’

To bring things back to the label and what you’re doing now, do you view United Nations as more of an art project than a band?

That’s the way I always viewed United Nations—as an art project, first and foremost. In saying that, it makes me feel terrible because those guys have become an awesome band. They’ve worked really hard together to form an identity, but to me, it’ll always be an art project.

So who’s in the band now?

It’s me, Lukas [Previn] who was also played in Thursday, Jonah Bayer, and Zac [Sewell] and David [Haik] from Pianos Become the Teeth.

And no one else is singing on the record?

No, it’s just me.

You’ve got a nice range then, even in your screaming.

That rules; thank you.

Given how you’re settling down these days, how do you get in a headspace where you’re screaming like that again?

A lot of it is the style of the band, which is fun, but once you start getting into that headspace, real thoughts, passion, frustration and anger comes out. There’s always a certain amount of that stuff not too far from the surface. Anybody—even a person who works in an office every day and has been married for 20 years—has that. It’s right there, whether or not you’re willing to look at it. That’s why Bruce Springsteen is still able to write such great songs. He knows how to look at himself honestly.