Words GAMALL AWAD

Set in the Veterans Room of New York’s Park Avenue Armory, Wednesday’s Ryuichi Sakamoto concert was simply billed as a “new work”. It’s a pleasant surprise, then, to discover the evening is devoted to the composer/iconic musician’s new album async, already out for a month in Japan and set to drop today in the US.

[youlist pid=”PLlxVAExh_bYbnN6c4q1EJxcv559obwOBt” width=”620″ height=”349″]

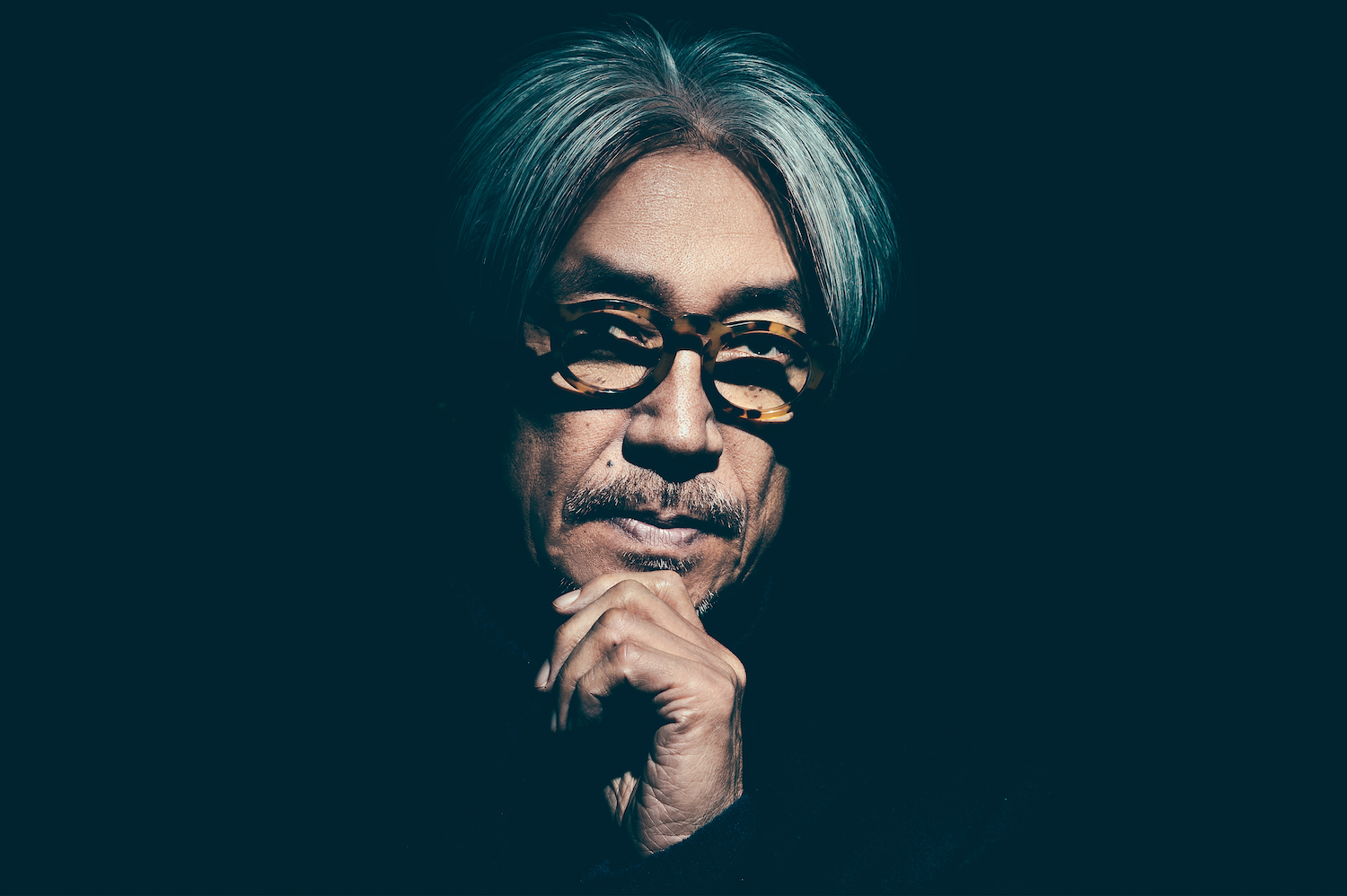

Playing to a rapt audience of around 160 people (including noted musicians Craig Taborn, Daniel Lopatin, and Spencer Doran), Sakamoto-san enters wearing an indigo linen suit, a black polar neck, hi-top sneakers, and his trademark tortoise shell glasses. He begins the 65-minute concert with “andata,” playing gentle melancholic opening chords on a grand piano with no lid and four microphones, positioned in the center of the small performance space. The piece’s church-like chords flow from a computer—used like a tape machine throughout the concert—until Sakamoto turns to his vintage EMS suitcase synth and gently detonates the opening theme into a kind of cosmic, angelic conclusion. A large screen suspended along the length of the piano casts a bright white glow, echoing the effect.

When listening to async, the music cannot be separated from Sakamoto’s recent two-year battle with throat cancer. It is not so much the sound of a man fighting for survival as it is a man questioning what life means after survival and recovery. If you dig deep into the many layers of Sakamoto’s discography, you will find many different musicians. In this concert, it feels as if he is expressing himself in his most personal manner to date—no small feat for such an accomplished and diverse musician.

With the screen displaying a Daido Moryiama-like black and white shot of an audience watching a blank screen, the tape rolls and “disintegration” begins—a John Cage-inspired angular piano composition that also brings to mind Sakamoto’s friendship with avant-garde artist Nam June Paik. In fact, photos of Sakamoto with both Cage and Paik can be found in the booklet for the Year Book 1980-1984 compilation that was released in Japan a few years ago. Paik would probably be happy to hear this subtle reference to his infamous Exposition of Music-Electronic Television event.

Like Paik, Sakamoto wrote in the program notes that he is moving away from traditional settings toward creating music in unique environments. Like Paik, Sakamoto is also trying to find ways to deal with the fixed and deterministic nature of today’s electronic music. He is seeking a way, as David Toop would note, to “disrupt time’s one-way flow (towards death) in traditional music.” In this live setting there is no way for Sakamoto to recreate the different elements moving in different time signatures, so he opts instead to add to pre-prepared piano with a wooden chopstick.

The complex use of multiple beats in “disintegration” is something Sakamoto does again and again on async. His own sense of time as a composer has been changed. In fact, talking to NHK TV recently, Sakamoto noted he can no longer produce enough saliva, so he needs to wake up a few times each night to drink water. His own sense of time is utterly altered. He also said he was shocked to see the recent changes in America, especially to see how little people are willing to step out of their own bubbles and listen to other points of view. He sees this as a breakdown in society that is not only happening in the U.S. (he has lived in New York for 30 years) but also in his native Japan. If anything, Sakamoto not only wants us to listen to music with fresh ears but to also use this skill of deep listening to hear more than our own hermetically sealed circles.

As “disintegration” continues, travelogue-style visuals by Takatani Shiro add yet another layer, appearing to reference the catastrophic Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004—itself a forewarning of Japan’s own tragic tsunami. Takatani-san has been working with video in unique ways since 1984, when he co-created the avant-garde performance and art collective Dumb Type in Kyoto. He has collaborated with Sakamoto many times across many formats. The two joined forces earlier this year with fog artist Nakaya Fujiko for a work at London’s Tate Gallery, and last summer they worked with Christian Sardet on an installation in Paris that resulted in the sublime ambient album Plankton.

The concert continues with “Life, Life.” Over a gentle plucked string and sho composition, Sakamoto plays slow meditative piano while the recorded voice of David Sylvian powerfully interprets a poem about dreams from Arseny Tarkovsky, the father of legendary Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky.

“No need for a date. I was, I am, and I will be. Life is a wonder of wonders, and to wonder.”

async itself is an album Sakamoto has called “an imaginary soundtrack to a film Tarkovsky never finished.” In many ways, this new music runs at a sonic parallel to the cosmic and mystical overtones of films like The Sacrifice, Mirror, and Solaris.

The parallel is made explicit on the next composition “solari,” a direct reference to Solaris. Sakamoto moves to his beloved Sequential Circuits synth and somehow, in this live setting, the song unfolds like the soundtrack to a lost Sergio Leone ending or the battle that brings The Good, The Bad & The Ugly to a close.

“Zure” follows with Sakamoto putting his hand inside the piano and plucking staccato chords. “Walker” opens with field recordings that sounds like someone walking through both a park and a city. Parts recorded at a Harry Bertoia exhibition last year are then added to the mix as Sakamoto moves from the piano to the guitar, playing in an abstract manner that recalls his recurring ally Fennesz. As the track moves toward a rising conclusion, Sakamoto veers into abstraction, surprisingly recalling Derek Bailey’s pointillistic style of plucking.

“ubi” opens with a sonar tone that, as the track develops, makes one think not of a submarine, but of the life support machine next to a hospital bed. Sakamoto plays the mournful, dirge-like piano chords that slowly shifted its tempo and tonality from the feeling of a death march to that of hard-won optimism and resilience. Sakamoto’s playing is a master class in both lush emotional playing and controlled restraint—utterly penetrating. It’s the kind of piano playing that has wooed his followers throughout his career and especially in the last decade as he concentrated quite heavily on piano music. The composition ends with the healing tones of singing and crystal bowls.

Next, “fullmoon” opens with feedback and the voice of Paul Bowles recorded in Morocco during the filming of Bertolucci’s The Sheltering Sky. Bowles’s knowing voice questions “how many times you will watch the full moon rise—maybe 20? And yet it will all feel limitless.” Sakamoto spent part of the track smiling, looking up at the screen of rotating grey circles within rotating grey circles. Maybe because this is his favorite track from the new album and he was clearly still enjoying Bowles’s wisdom, which was also read out in other languages by Shirin Neshat, Carsten Nicolai, and others. “fullmoon” is the work of a mature composer, an aging man coming to terms with mortality, questioning his own choices and desires against the reality of time as finite.

The title track follows—much of it pre-recorded as it would be unrealizable by a single performer. Its aggressive atonalistic Penderecki or Takemitsu-style percussively played strings suggest internal cellular battles as the grey-on-grey circles mutate into light and other shapes on the screen. After the intensity of “async,” the metallic tones of “tri” (recorded with the International Contemporary Ensemble) fill the space in an act of cleansing.

For “Honj,” Sakamoto rises and moves to the side of the piano toward two sound sculptures designed by Bertoia. One is a six-prong unit of medium height and the other a curved row of rods. Sakamoto plays them with a brush and mallets, creating long, short and unusual tones while long sine waves and samisen sounds merge around him. Sakamoto moves to the other side of the piano for “ff,” approaching a large sheet of glass, first coaxing the edges of the pane with a music fork, then rubbing and dragging soft mallets across its surface for an otherworldly composition.

Looking at Sakamoto from the other side of the glass pane, it’s hard to not think of the whole thing as some kind of metaphor for his illness. Behind the glass, suffering—the long scrapes sounding like moans and groans and squeaking beds being wheeled around. The screen above him goes from clouds to digitized clouds to a morphed combination of both and into slow-moving dissolves.

The concluding garden sounds like the musical equivalent of the garden modernist Japanese garden designer Mirei Sugimoto created for his own house in Kyoto. There, the blue stones are lifted up toward the sky, acting as a kind of portal for the energy of heaven to transmit down to earth. Here in performance, the screen above Sakamoto is entirely white. On his aged Sequential Circuits synth Sakamoto coaxes a pulsing bass modulation while the large church-like organ sound from andata returns in a more atonal mode. Sakamoto appears to hint at the afterlife but at the same time he reaches for an uplifting finale of deep peace. After the tranquility of his ending the air is overwhelmingly positive and charged. The audience stands to give an ovation. Sakamoto bows gently and smiles as he slowly exits. He looks satisfied that this intensely personal music and challenging process has clearly moved those in this intimate space.