Words ANDREW PARKS

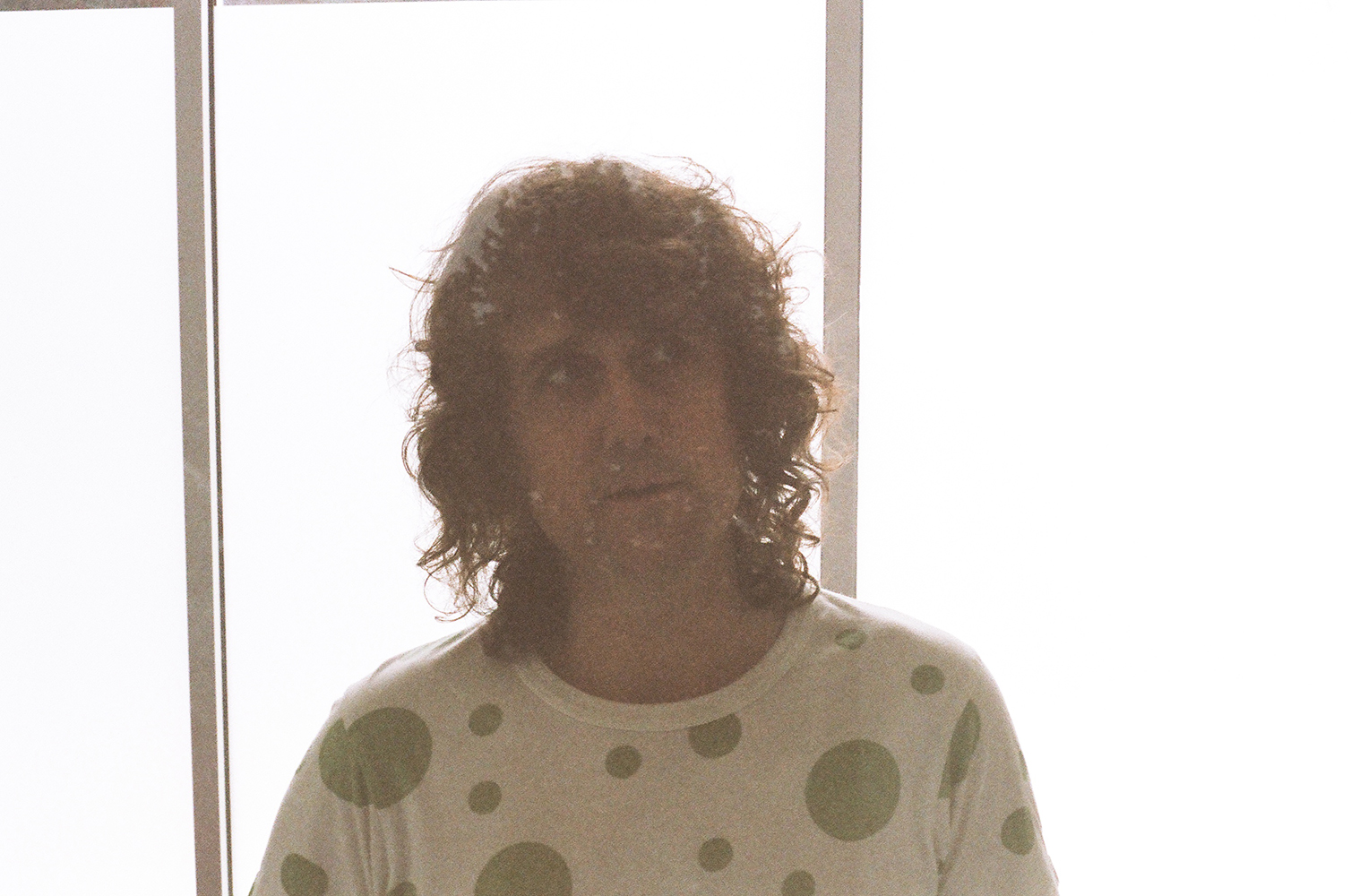

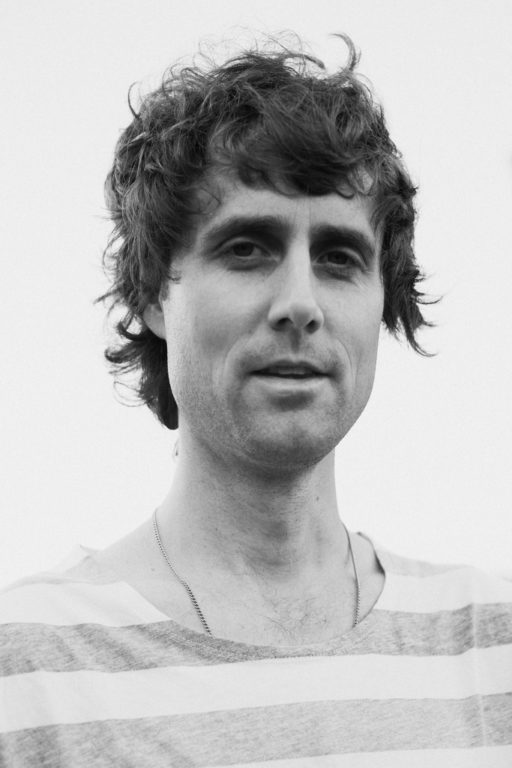

If there’s one thing I remember about meeting Luke Jenner 12 years ago, it’s how reserved he was. Some would even say the singer/multi-instrumentalist was guarded. Or ambivalent. Or just plain over it—over doing press (our interview was for an Urb cover story), over touring, and over being in a band that didn’t know what it wanted to be anymore.

And who could blame them? The Rapture was being pulled in a million divergent directions by the time they finished the follow-up to their flawless debut Echoes. That goes for everything from their top-notch management team to the three very different producers (Danger Mouse, Paul Epworth, and Ewan Pearson) that worked on Pieces of the People We Love.

“That was one of the worst times in my life—literally,” explains Jenner. “I look back on it now and am glad I didn’t die. We’d gone through this massive DFA breakup…. James Murphy was one of my best friends at the time, and I’d lost him because I was trying to stick up for [bassist/singer] Mattie [Safer]. Then that totally went sour. I’m just glad I’m not there anymore.”

Judging by how much his demeanor has changed between the spring of 2006 and our intense conversation last week, Jenner’s not even on the same astral plane anymore. He’s in a place that’s overwhelmingly positive, and steadfast in how self-aware he is about making art, facing death, and being a better father.

In the following exclusive, we discuss Jenner’s entire career, from the rise and fall of The Rapture to the many projects that are waiting in the wings for the coming year, starting with this Friday’s Glittering Jewel 12” on Life and Death. It’s the most widespread release yet from Jenner’s new Meditation Tunnel alias; check out an exclusive listen to its B-side near the end of the extensive conversation below and a personal essay about one of Jenner’s favorite ambient records over at our new self | centered site….

self-titled: What are you up to this week?

Let’s see…. I’ve got a show today on The Lot Radio. What else am I doing? My kid just started seventh grade. And it was my wife’s birthday yesterday. My college roommate is playing a show tomorrow in town, so that’s cool. It’ll be nice to see him.

Who’s that?

He used to be called Casiotone For the Painfully Alone, but now he’s called Advanced Base.

Oh really? That was your roommate? I’ve been meaning to check out his new stuff. Is it similar to his old records?

Well, he got tinnitus at some point. One time I loaned him one of my amplifiers for a show and he blew it up, because he used to play Casios through chains of distortion at full volume. I don’t know how you quit a band when you’re the only member, but he did that and decided he wasn’t going to play his old songs anymore. I think shows are about creating a mood, and he creates an amazing one. I don’t think it would work for other people, but somehow he figured it out.

Was he your freshman roommate?

No, I lived in this punk rock house and he moved into the back room. We used to have to take the trash out over his bed.

[Laughs] What do you mean?

Well, he basically lived on the back porch. It was on the third floor or something, and on these stilts, so it was kind of falling over. It’s a good thing he didn’t die or something.

Ah, the punk house days.

I had a great time! The sky was the limit. No one cared, and you could do anything at any time. All of our first bands’ shows were there, including The Rapture. We’d just have a party. That’s how every band started, basically—in the living room.

That was in San Francisco then?

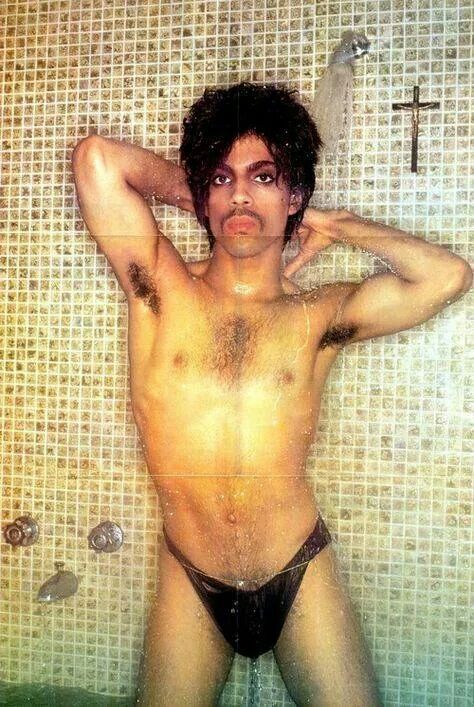

Yeah, it was at 24th and Mission. It had a poster of Prince naked in the shower on the door, so everyone called it The Prince House. It was that picture from Controversy, where there’s a crucifix in the background and he’s wearing a purple Speedo.

Got any other good memories from that house that you’d like to share?

We had a party one time and Modest Mouse showed up. My roommate, who became a professional writer at some point, lost her mind and was trying to get me to stand in front of them so she could take pictures.

So that helped you realize how crazy people get over rock bands?

It was cool, yeah. We were just a bunch of literary college weirdos. I remember somebody left their furniture in our front room and they didn’t come and get it for four months, so we just put it on the roof. They came back and asked where the furniture was, and we were like, ‘I don’t know.’

Is it weird how San Francisco went from being a haven for the arts to the epicenter of the tech industry?

Yeah, I don’t know. One of my best friends is the world music buyer for Amoeba Music in Berkeley, and even Berkeley is kinda weird. Everyone’s in Oakland now, and Oakland’s pretty far away. Neighborhoods are a lot closer in New York. I left San Francisco in the late ’90s. It was perfect for me. There wasn’t much of a music scene, so you could just do what you wanted. I don’t know anyone who lives in the city proper now. I hear little rumblings of stuff. But it has a cool history, you know? Things like Target Video and Boyd Rice. I don’t know what’s going on these days, really.

Does it feel good to not know, since it lets you develop your sound without being impacted by outside influences?

Yeah, I mean…. At some point, I got hyper-focused on Europe because I toured the U.S. for like a million years. And then I married a French lady. And my mom was British. It’s good to unplug; being a professional ‘cool guy’ 24/7 is terrible. Thinking about yourself as being important in any way is a really bad way to live your life. The people I know that wake up and think they’re awesome are kinda miserable. I’m more interested in liking myself than being successful. Or to put it another way, my definition of success is liking myself.

Did you feel like you had to be someone you’re not for quite a few years?

I just started feeling all of this pressure, as a songwriter, to fund all of these people’s lives, whether it was other people I played with or managers. It was like, ‘You better write some songs so we can all live, dude.’ Also, the more successful you get, the more you’re around people you don’t know. And you play for people you don’t know.

You start out booking your own tour and staying on someone’s floor, looking at all of their books and hanging out. But then you’re suddenly at a four-star hotel in Brazil and a car comes to pick you up. It’s cool; it’s fine. I don’t think I could sleep on people’s floors anymore, but at the same time, the search for meaning is more important. Art or music has always been a vehicle to know myself more than any other thing. It’s pretty personal. And at some point, success rips that apart.

One of the reasons I took so much time off is I got hit in the face with tons of family trauma from growing up. And I had a little boy, so I was like, ‘Dude, if I don’t pause and face my own stuff, my kid is going to eat that stuff.’ And I’m not cool with that. That’s more important than continuing to climb some ladder. I already got way farther than I wanted to go.

Where do you feel you’re at, mentally, as a father right now?

It used to be horribly painful, but it’s awesome now. I really like being a father. It’s so amazing to know that you’re so clearly not the most important thing. In a lot of ways, that’s the antidote to being this ultra-powerful, golden goose-laying thing. It gives you balance. My kid doesn’t give a crap if I played on a stage in front of a lot of people or if I was on TV. He literally doesn’t care. He just wants to know if I’m proud of him and if I have time to listen to what he’s interested in. If you want to make a kid happy, you just have to pay attention and ask questions. It’s the same with any person, really. That’s how you love somebody.

What is your son interested in? Anything that surprises you?

My relationship with my dad was all about sports, so I assumed my kid would also be amazing at sports. But if you lined him up with 10 other kids, he’s the last picked. His zone is video games and anime. He’s like a dungeon master with really long hair—a sharp kid who’s very intuitive and artistic. I just thought I was gonna be a baseball coach. I did that one year, and he didn’t like it. So I said, ‘Thanks for trying that. What do you want to do?’

So he’s basically like a character from Stranger Things?

Absolutely.

It’s interesting that you were so into sports growing up. There’s often that clear division between the jocks and the artistic kids. Did you reach a point where you had to choose between the two?

I didn’t start playing guitar until I was 17. I was on the varsity baseball team. My dad taught at the University of Hawaii when I was a kid and used to take me to baseball games. The players would sign baseballs for me and drive me around in the golf carts. I thought they were gods, you know? I wanted to be that. But once I got to high school, I didn’t really like the people I was playing with. They were dicks—these jerks. It was probably the biggest crisis of my life. I remember going home after practice and laying in my bed, staring at the wall in the dark for hours with my cleats on. I was lost.

But then my friend started taking me to local music shows and this kid on the baseball team had a guitar and a little amplifier. So I borrowed it. I was playing Dungeons & Dragons a bunch then, and my dungeon master wanted to start a band with me, so we started writing songs on a tape recorder. But I was like 17 or 18; I got a really late start. This was San Diego in the early ’90s, right after Nirvana happened—a really exciting time. There was lots of local press and good record stores where I’d buy 7-inches every week. It was just a fun time to be around music.

Does one show in particular stand out from that period—one that really inspired you?

The best show I saw in that era was this band Truman’s Water from San Diego. It was a band John Peel really loved. I remember they had just played in front of hundreds of people in England, but they ended up playing in front of just me and my friend. It made me think, ‘Wow, you can leave San Diego and go somewhere else.’ They were also a weird band that was into Krautrock and other stuff I hadn’t heard before. It was like an art project. San Diego is a military town; there are only like three weird people there. And they all know each other and complain that no one likes the records they like. Which was my experience too. It was like the land of blink-182 and fart jokes.

So you got out as soon as you could?

I wanted to, but my mom was suicidal when I was growing up. She killed herself the year my son was born, which was a big deal for me. My job as a kid was to keep her alive. My dad would go off on these long business trips and I’d be home, trying to get my mom to not kill herself. I was in junior college for like two years in San Diego because my mom would just fall apart if I left.

All of my teachers were like, ‘You’re a really smart kid, but you just don’t care about anything.’ And I was like, ‘Well, that’s kind of true. I just want to be a musician.’ And they were like, ‘That will never work. You need to suck it up and go to a good school.’

So I was like, ‘Okay, I’m gonna press pause, because my mom is trying to kill herself.’ And I couldn’t really talk to anyone about it. I couldn’t have people over at my house either, because it was this weird drug den. My mom was just super high on prescription drugs all the time. She was bi-polar, so she’d be up for, like, two weeks and out of her mind, saying crazy stuff.

No one knew that was going on. The kids I grew up with were like, ‘Dude, that sucks. I wish you would have told me.’ But what would they have done about it? I just made it through. And once I got out of there, she fell apart and got a divorce from my dad. Because I was also keeping their marriage together. I was basically married to my mom emotionally. And that’s why I related so hard to my two favorite singers, David Bowie and Robert Smith. They have this really intense emotional intelligence that you can hear in their music, but it’s born out of getting their ass kicked [laughs].

My mom was an abstract oil painter and an art teacher, so I grew up in this house with giant paintings everywhere and stacks of art books. I thought that was normal—that everyone’s mom was an abstract oil painter. She’d be at the supermarket in lime green, fluorescent high top Reeboks, and a fanny pack and crazy hair and freckles. She didn’t look, or act like, anyone else’s mom. She’d be in my ear all the time, about how ‘people in San Diego don’t dress right. They’re stupid. French people are the best.’ And my dad thought travel is the best teacher, so he said, ‘If you can get people to pay for travel, you should do that.’ I learned a lot from both of them; my dad is a brilliant dude, and my mom was super intuitive and really cool. But she was also really vindictive and enjoyed causing people pain.

That must have made you feel like you couldn’t live your own life sometimes.

No adult human should talk to their parents every two days. That’s a red flag. There’s no way that’s healthy. It’s not good for anyone.

Well, it’s like you’re living with another kid on some level.

Absolutely. That’s a really good way of putting it. When my mom killed herself, I had a really nice realization that helped me grieve, which was my mom was more like my kid than a parent. And when I lost her…. You know, people say the hardest thing in life is losing a child. And I lost my child, for sure. I never had a mom in a lot of ways. I had to look for mentors who were able to nurture me through a lot of child development I never had.

Were you an only child?

No, I have a kid sister. She’s six and a half years younger. That’s a huge difference when you’re growing up. She kind of became like another… my dad was always passed out drunk. He was a really bad alcoholic, so I always had to be there for my sister. She looks at me as this father kind of dude. So, yeah, I kind of had several kids growing up. Well, how are you supposed to be a kid if you have kids? How does that work?

Now I can understand though why it was hard for you to enjoy The Rapture’s success early on; it was because you had other shit going on back home.

Oh man, I was terrified. Every single day was like, ‘My wife’s going to leave me because I’m not there.’ I had this therapist in 2003 and he basically looked at me straight in the face and said, ‘You can choose between your mom or the woman of your choice, but you cannot do both at the same time.’ And I knew in that moment I would choose my wife. And I also knew in that moment that [my mom] would die. All in, like, two seconds, you know?

I had all of this wreckage inside. I was meeting David Bowie, going on tour with The Cure and Daft Punk, and living all my dreams. And I was more miserable than I’ve ever been in my entire life. I’d achieved every bar I’d set for myself, but I was still sitting on a time bomb.

Well success leaves you no time to really process everything.

I was a philosophy major in college probably because I was trying to carve out time…. Being on the road allows some of that, but it’s kind of limited.

There’s a limit to travel, too. You can learn a lot from it, but at some point you’re just doing the same stuff. Like I’ve been to Australia 27 times and I’ve met a lot of new people—a lot of different personality types and cultures. That’s all cool but you kind of hit a limit with that outward path. You have to go in. I mean, you don’t have to, but it starts to get boring in a way I could have never conceived of until it happened.

A lot of that has to do with how a band travels, which is often between major cities that have similar-looking coffeeshops, bars, and restaurants. It can feel a little repetitive after a while.

For me, I think it was a real transition to people. I used to be really terrified of them for a good reason—because the two people who raised me are crazy. I love them, but they’re not healthy, so those were the kind of people I was attracted to—just magnetized.

So people were scary, and then at some point, I stopped being afraid of my parents and my past. I still attract the best and the worst people; that’s never going to change, but I really like people because they’re totally unpredictable. I don’t know what they’re going to do. My favorite thing about New York is it’s this endless supply of interesting people that turns over all the time.

I definitely get that. I lived in New York for 10 years, and that’s one of the things I miss the most—being plunged into humanity every time you leave the house, whereas living in a place like LA is very isolating. It’s as if you’re living behind panes of glass.

Yeah, that’s the culture I grew up in. I spent most of my formative years in San Diego. I didn’t even have a car, so that was super isolating. It’s like a bunch of gated communities. LA’s basically a suburb. I came to that realization a while ago. It’s not a city. It’s a really fancy suburb—the nicest suburb in the world.

Sure. You go from strip mall to strip mall.

Exactly.

And you’ve been in New York for a while, so you’ve seen its revolving door of artistic people many times over. What are you excited about there right now?

I think The Lot Radio will be looked back on like it’s a thing, the same way things were with my first New York moment: working at Plant Bar. The Lot Radio is the first time since then that’s felt like that: a real moment. But I also didn’t want to talk to anyone when I got successful. I didn’t go out for a really long time.

In the last few years, I’ve gone out more to see who’s doing what and talking to really young kids. I mean, I’m 43, so hanging out with 22 year olds is amazing. I’m really interested in helping other people do what I already did. I still like making stuff because I have to, but I’m transitioning into being a dad and a mentor. Like in the ’80s, William Burroughs and Andy Warhol were just around. You could ask them questions about whatever and they would answer you. I’d love to be that kind of character. Because I was really scared when I was 25. It was touring a lot and terrified of everything. I wish I would have had somebody who was 43 who was like, ‘Dude, it’s okay. A lot of people probably don’t understand what you’re going through, but I hear you. Here’s some stuff to think about, and some people to talk to.’

Everybody wanted something from me when I was 25. Everyone was grabbing and trying to control me. That was flattering, and nice in a way, but I just wanted someone who wasn’t trying to grab me.

You must’ve learned a lot though from meeting people like Robert Smith or David Bowie.

Yeah, in a way. But to be honest with you, I never met anybody who could answer what I wanted to answer. People could tell me how to write songs or be more successful or they could tell me about what to avoid in business, but no one could tell me how to balance a life as a husband, a father, and an artist. All the people I’ve met in life are good at being one or the other; no one’s nailed that balance.

That’s one of the hardest things in life, isn’t it?

I think the hardest thing in life is to have a romantic relationship. I’ve never been proud of muddling through anything. I’m more proud of [my marriage] than any of my artistic endeavors. They’re cool, but they don’t have as much personal meaning.

When I was growing up, my parents didn’t like each other. I mean, they loved each other in an abstract way, but practically speaking, they were just beating the crap out of each other or ignoring each other or being hurtful. I literally had to walk into a therapist’s office many years ago, and say, ‘I have no fucking idea how to do this. Please, for the love of god, help me. Because I’m gonna screw this up. There’s no way I can do this on my own.’

Did therapy help? Part of me feels like therapists are only half listening to you. I guess it’s all about finding the right person.

It wasn’t just one therapist. That started me on a path of many relationships and making a lot of mistakes. My marriage didn’t really get good until a few years ago. Five or six years ago, I wasn’t even sure it was going to work out. I wanted it to work, but we had to each work on ourselves first.

And my wife was pissed. She was like, ‘Well, I’ve been through all this stuff with you. Do you want to be with someone else?’ I said, ‘No, I want to be with you. I chose you.’ And she was like, ‘Well do you know anyone who has the kind of relationship you want?’ And I was like, ‘Well, no, but I’m going to figure it out.’

And we did; we figured it out. And our kid’s a lot happier. He was in kind of in a weird spot. He was getting bullied and struggling with school, so they wanted to put him on like prescription drugs for paying attention and stuff. I was like, ‘No way.’ Now he’s super happy because our relationship is good. Kids can’t run away from you. They just absorb all of our energy, so if you’re good, they’re good, for the most part.

Has he found his social circle now then, or are you still pretty worried about him?

No, he’s awesome. Everything clicked about four years ago. He found these nerd beehive places that have a lot of games. He’s really good at that stuff; he’s even making his own game now. I have a friend who’s helping him make this board game and we’re going to test it out soon. He’s awesome, man.

He had his first really tight best friend this year. It’s almost like a romance. I remember when I first got into seventh grade. That’s when you start talking to people on the phone and getting really deep. It’s almost like you’re practicing for romance without any of the romance part. You’re just getting really intimate with somebody and sharing everything. Like my kid spent the entire day listening to “Mr. Blue Sky” by ELO because his friends told him that he should listen to it.

Those were the days—when we’d actually talk on the phone for three hours.

I still do that shit. That’s my favorite thing to do. It’s part of my self-care. I love talking to people. That’s where I get a lot of my ideas from when I’m writing. It all feeds each other.

Does the way the world’s going worry you at all? I mean, it feels like we’ve lost the simple ability to communicate with each other.

There’s some truth to that, but my kid loves talking to people. You don’t have to talk to everyone; you just need a little collection of people. It’s kind of like how people say no one reads books or listens to records anymore. People still read books; it’s cool. Not everyone does, but most people didn’t read books anyway for most of history. There’s always going to be people who like books and deep things like contemplating the nature of the universe or death. Like I think about death every day, but that’s not normal. It’s not grim, though; it’s a reminder of what I’m doing—a course correction. Like, ‘Well, I’m going to die, so is what I’m doing today in line with that? Am I spending my time well today?’

My kid is really happy, really interested in stuff. He’s a fan of a lot of things. I think that’s what I lost. The more successful you get, the harder it is to stay being a fan of stuff. The people I know who are the happiest are, like, 60 and still super psyched about whatever they’re super happy discovering new things.

Is that level of curiosity something you lost along the way and are starting to regain now?

Yeah, I got super into fishing for a few years, and then I got into playing softball at the park. I’m a seeker. I can’t not seek. Like I got super into visual art recently, like painting, which is getting closer to my mom. For a long time, it wasn’t safe to touch any of the areas that my mom occupied. But yeah, I’ve always been a seeker. I wasn’t always happy. Like I feel like it really started to feel comfortable and like myself maybe like eight years ago. Since then, I’ve been pretty good. I’m not pessimistic. I mean, sure the world has problems but I’m not worried for my kid. And neither is my wife. We’re good.

This is kind of a big question, but what was the biggest thing about yourself that you kept struggling with? Why weren’t you happy before?

Well, how abuse works is someone opens you up like a trashcan and throws a bunch of shame into you. Being able to identify what that shame is, and let it go back to where it came from is really valuable and liberating, because then you don’t have to carry all this crap around. You realize it’s not your fault that people hurt you. Most people are carrying around so much stuff they’re not even aware of. That’s an average person’s experience of life.

Figuring out what your baggage is, so it’s not on your back the rest of your life?

Yeah but who the hell does that? You have to take a lot of time off and most people aren’t interested in that. They’re not philosophical in any way. They’re not delving into who they are like. That’s what art is for. Although people use art to torture themselves as well, including most of my heroes. Have you seen the David Bowie documentary The Last Five Years? Well, he talks about how he’s still dealing with themes of alienation and loss and suffering, right up until his dying day. That’s really hardcore. And it’s not what I want to do, even though you can’t be any cooler than David Bowie. He’s the coolest person of all time. I went to a museum exhibit about him in Brooklyn and I couldn’t even move because of how his death was this whole social media masterpiece. But David Bowie was just this guy from England. Of course, he left an immaculate corpse of work behind, but at the end of the day, if you’re not enjoying any of that, you’ve failed.

Louis Armstrong is another one. He essentially invented jazz and modern singing and was far and away the best musician of his time, and he died high every day. He hated himself. I’m sure some people would say that’s being too blasé—painting his life with such a broad brush, but this is coming from someone who’s mom was an artist and killed herself. She did not like herself, and she didn’t like me or anyone else around her as a result. I remember Kurt Cobain killed himself right around when I graduated high school. My mom brought me Time magazine and said, ‘This is what happens to bi-polar people.’ I was like, ‘Cool, I guess?’

I just didn’t want to be any of that….. It’s just awful. It’s really gnarly when you get close to it and it’s not abstract. When it’s actually someone you know, it’s gross.

Right, there’s nothing romantic about that.

It’s not sexy; there’s nothing attractive about that.

You stopped drinking over a decade ago, right?

Yeah, it’s been 10 years now. My wife was like, ‘I can’t really connect with you when you drink.’ I fought her on it for a few years, and we went to couples counseling. One night, before our kid was born, she left me for the night. She just didn’t come home. I’m really lucky to have a wife who is brave enough to stand up to me. If I hadn’t married her, I’d probably be dead. If I had a girlfriend or a wife who was just like willing to go along with everything—’yeah, keep drinking a lot; you’re a rock star now’—I’d be probably be dead. [Laughs] But she was like, ‘I actually care about you as a person. When you are hurting, it hurts me.’ That made sense; I didn’t want to hurt her, so I stopped hurting myself.

Were you drinking a lot because you couldn’t handle the day-to-day pressure of everything?

I mean, I’ve always loved drinking. My dad drank every day; he doesn’t drive a car after 4 in the afternoon because he knows he’ll be legally drunk. He just plans his life around it. He was fucked up every single day when I was kid. I used to sit on his lap and eat marijuana seeds out of a tin while he was rolling joints when I was 4. And he would give me sips of beer with water.

I remember the maddest he ever got at me was in high school. He came home and I had drank all his beer. He was like, ‘Never fucking do that again.’ He was pissed. I remember he was like you can drink as much as you want, just don’t mix it with anything else because you might die. Other than that, you’re good to go.

When I stopped drinking, my family actually felt sorry for me. Because it was like a family thing. My grandmother was like a crystal meth addict, you know what I mean? That’s what we do. So it was almost like I was leaving the family when I stopped drinking.

That’s really intense, man.

[Laughs] I’m sorry; I’m pretty categorically incapable of having a casual conversation. Which makes things interesting, but I have to watch myself.

Let’s bring things back to what you’ve been working on then. You must have a lot of material you’ve been working on, and have either scrapped or ready to release.

Yeah, I’ve made tons of stuff. I’ve always worked with really good producers, so I wanted to do that. At some point, I didn’t know how to record anything. I was afraid of GarageBand; like I would sit there for five minutes and get frustrated. But then I eventually graduated to Logic and started playing around with other stuff, like Ableton.

When the Rapture broke up, or stopped, I got my own studio space for the first time. I got two drum kits and would just play the drums every day. I wouldn’t record anything. I just wanted to play drums, because that was my dream when I was little. When I was 4 years old, my parents were like ‘you can’t do that.’ Then I got a drum kit when I was 16 and locked myself in my room at 16 for three days. They were like, ‘The drums have to leave or you’rleaving.’

I started a new band with three people who’d never played music before recently. It’s called Seedy Films. We are playing a show with Bush Tetras at Elsewhere on October 8th. I really relate to how Brian Eno was more of a thinker than a musician. I mean, he makes some amazing music, but he has really great ideas. I have this idea that you can teach people techniques, but you can’t teach them taste. I’ve been in so many bands that had questionable taste and it always ends badly. Because saying you don’t like someone’s taste is like saying you don’t like someone’s face. You can’t change your taste, really; you can hone it, but you like what you like.

So I had these three people I was already friends with who had really great taste, and I asked them if they wanted to play music. So I started teaching them and we put together this band. Writing songs is the easy part for me, so I taught them how to write songs and I play drums in the band because… why not? I’ve already done everything else. So that’s really fun.

I’ve also learned how to produce music. For the past few years, I asked this guy Joakim to mentor me. I’d just sit on the couch in his professional recording studio and we’d mix other people’s music. I’d sit in the back and ask questions. I went to Europe and worked with this guy Barnt for a while, too. He became another mentor. And I became friends with DJ Tennis; he’s putting out the new Meditation Tunnel record. Six years ago, he was like, ‘Okay, I’ll put a record out for you, but you can’t call it Luke Jenner.’ I was like, ‘Okay.’ And then he was like, ‘Also, you’re going to try to produce a lot of music and I’m going to tell you it’s not good enough for a long time.’

And he would; he’d come every few months and say, ‘Yeah, that’s not good enough.’ Then a few years would go by and he’d say, ‘Okay, this is good; make some more stuff like that.’ It was a really long process, but I had the time. I was home, and I wanted to figure it out. It’s miraculous to me that the record is coming out and people like it, because seven years ago, I was afraid of sitting in front of a computer for three minutes. I didn’t know how to do anything. I could write a song on a guitar, record it on my phone, and take it to the band, but I didn’t know how to actually make a composition.

It must be humbling to go from people saying how awesome you are at the height of The Rapture to having people like Manfredi [Romano] tell you what you’re doing isn’t good enough.

I’ve always loved that. My dad was a sports psycho. We would play one-on-one tackle football when I was 4 and he’d kick sand on me every time I went down. He turned me into this weird sports killer. He would also say that if I could touch a football with my fingers, then I can catch it. He wouldn’t accept anything short of that.

So I’ve always sought teachers that were hard on me. Like James Murphy is probably nice to work with now, but when DFA started and the Rapture put out its first record—”House of Jealous Lovers”—he kicked our fucking ass. He was horrible. He didn’t give a shit how we felt; he just wanted to get it done. I’m sure he’s super mellow now and success has changed him, but I remember how smiley he was when he first started doing interviews and thinking, ‘This is not the dude that I know.’ But that’s cool—that we got that level of work done.

I’ve always needed a certain amount of striving and struggling, so I’m in a really weird place in my life, where I don’t have something to struggle against. I’m sure I’ll find something, but that’s always been where I’m happiest—when I find something I want to explore. Because I’m a really good student. My dad trained me to be that way from a really young age. I don’t like to be treated badly anymore; that’s off the table. But my favorite thing is having someone close be hard on me but encouraging. Which is what Manfredi did. He wasn’t mean; he just told me to try harder.

Well there’s a difference between telling someone to go back to the drawing board and telling someone to rip their work up because it’s terrible.

Exactly. There’s a really great Philip Glass documentary about these two teachers he had. There was this French piano teacher who would hit him with a ruler if he didn’t play something right, and there was this Indian classical music guy. He said they both taught him the exact same thing, but he’ll never speak to the French one again.Those kinds of things really stick with me.

A big part of my life is I like being a teacher also. I’m more interested in that than anything else. Because I had to take care of my mom and my sister, and when I started the Rapture, I had to teach everyone to play what I wanted them to play. Being a bandleader and a songwriter, you have to drill people for years to get people to play how you want them to play. It’s like being a classical music composer. So I see it from both sides.

If songwriting and playing the guitar come naturally to you, couldn’t you have just done a traditional solo record?

For me, it’s about doing something new and then circling back to what I’m comfortable with. I don’t really believe in ditching things forever. I know I can sing and I know I can play guitar, so I have those songs in my back pocket. That’s a given. But that’s not meaningful to me. Learning something new is. What I know how to do best is get in a room with four people and tell them what to do. And then play a show. The Meditation Tunnel record is the opposite of that in every way possible.

What are some other ways it’s different? It must be daunting to have so many possible roads to take it.

I would literally go to my studio 7 years ago, work in front of a computer for 10 minutes, and get a horrible stomachache because it wasn’t immediately clicking. Then I’d just go home and lay in bed for two hours. I did that for years. Another thing I had to unhook is the killer instinct my dad put in me.

At some point, I got five instruments—a trumpet, a clarinet, a violin, a saxophone, and a flute—and a lesson on all of them from a friend, and played them as an exercise in imperfection. Meditation Tunnel, and me becoming a producer, is this exercise in doing things imperfectly. Being compassionate to myself in this uncomfortable space. Making music in front of a computer is all about listening; when you’re in a band and you’re in the room, it’s all about action. Kind of like sports.

The name Meditation Tunnel comes from this $10 kids toy I found; it shoots these red and blue lights all over the room. Most of that music was made in the middle of the night, when I couldn’t sleep. I would sit there with this light on and just listen to stuff. I got really into ambient music, and treating music as a meditation rather than a sport. And listening instead of talking. Success became finding an ambient loop I could listen to for a few hours and not get bored. If you can’t listen to a loop for eight hours straight, then you need to find another loop.

Have you done some ambient music too, then?

Meditation Tunnel is essentially ambient music with a kick drum. That’s how I approach it. It may be a stretch of the word, but performing is ambient in a way, too. When you have a good show, you don’t remember any of it. Or if you’re playing sports and you have a really good game, it feels like five seconds went by. Or if you DJ for four hours and everything clicks, it just happens.

Do you feel comfortable as a producer now?

I do, to the point where I’d like to produce other people. I think that’s such a precise place to be. It’s a super intimate thing to have someone take your hand and help you give birth to songs or steer the process. Like I spent four hours with this kid from The Lot Radio. He asked me to listen to all of this music. The first three hours of it was super mediocre, but at some point he played this really amazing thing he had done in college. He had gotten real musicians to play this kind of avant-garde classical music piece and it was stunning.

I was like, ‘What the fuck was that?’ And he was like, ‘Well, I’m kind of embarrassed of it; I’m not really sure how I feel about it.’ So I told him I’d help him if he wants. That’s the most luxurious place to be—to have the time, energy and expertise to spend on someone and not need anything from them. It just feels really good, to alter someone’s perception of reality in a positive way that’ll probably last forever.

Is Meditation Tunnel your focus now, then?

No, I was basically in a long-term marriage with the Rapture, which was like a gang. And I was the worst one in it; if someone else tried to do something outside of the gang, I was like, ‘You can’t do that. You’re cheating on me.’ And at that point seven years ago, I realized this is totally insane. I’m hurting myself as much as anybody else and I just want to try everything, whether it’s writing, painting, producing all kind of music, or being in a band with people who’ve never played before.

I guess it’s like my marriage; to have a successful marriage, you really need to talk to other people. I really love my wife and she loves me, but we really weren’t talking to anyone else for a while. That’s bad. You can make that work, but it’s kind of anorexic. To have a healthy marriage, you need to have at least five other people you can speak to intimately and cultivate some sort of continuity with.

What would happen with the Rapture is I’d write a bunch of music and it’d take years I would write music and then would take years for it to come out or for the band to even play it. To even get four people to schedule practice is really hard. So to listen to ambient loops in front of my computer at night with a kid’s light on is really nice. That doesn’t mean I don’t want to collaborate again. I think collaborating is fantastic and necessary, but I never really collaborated with myself.

And in my marriage, I always expected my wife to take care of me. She used to say, ‘I really want you to be my partner.’ And I’d be like, ‘What are you talking about?’ At some point, I figured out I was carrying this wounded kid inside of me that needed her to essentially be like a parental figure for me. I was relying on her to take the weight of this pain I was carrying around. Not always consciously, but if I was uncomfortable, I’d look for her and she would soothe me.

That took a toll on her, to the point where she couldn’t take care of herself because she always had to be there for this unending pain that I had. When I took that pressure off her, she started becoming a really happy person. She started her own business for the first time in her life, and she started to have friends again, and she started to smile.

I think what I’ve realized is it’s more important for art to be an extension of your life than the other way around. I used to think my reason for living was the Rapture and being successful and getting people I looked up to to like me, but once I did that, it didn’t make me happy. I had to completely alter my way of living—to put my life first and try to make music out of that.

For years, I couldn’t write any music, and now I have so much coming out of me that I literally don’t know what to do with it. I have tools now as a producer and a collaborator to be able to do stuff and have it be an extension of wherever I am. It feels…. different, really pleasant, just a super nice feeling. Most of the musicians I know are hyper-focused on what other people think, to the point where they never get to know themselves. The only time they’re happy is if they get a good review or have a successful tour. But it’ll last for 20 seconds and then they’re back to feeling miserable.

Were you that kind of person before? When we met 12 years ago, you didn’t strike me as the kind of person who gave a shit what journalists think.

I think I’d already met David Bowie and Robert Smith by the time we talked, so it felt like no one could say shit to me. Not when two of my favorite singers think I’m awesome. David Bowie was like, ‘I really like listening to your music when I’m driving my car or folding my laundry. And I’m really excited to hear what you make next.’ It’s like, ‘Oh my god.’ I’d basically completed two of my life goals. No critical opinion really matters beyond that. That took a lot of pressure off of me but it still didn’t solve this internal father problem I had. I was still beating myself up, essentially.

Have you kept up with what the other guys from the band are making now? Everyone seems to be making really different stuff.

I follow it loosely. For a long time, it was just really painful between me and Vito. I’ve known him since I was 9 years old. I think I’d let go of my wife before Vito in terms of holding him accountable for me. I woke up a few weeks ago and was like, ‘I don’t need you to be my family or interested in me in any way. I don’t need anything from you.’

For a long time, I was holding this space for Vito, in case we’d eventually be super close again. If we do, that’s cool; I’m open to that. Not in a fuck you sort of way. Vito has probably been the biggest challenge of my life. I know my dad’s kind of an asshole and my mom was suicidal, but Vito is someone everybody likes. He’s very personable, supportive, and good at listening.

I think it’s been cool for him, especially, to just do other stuff outside of the band. Because I was so tyrannical and needy for so long. I needed to have it my way, even down to the drums. Like ‘you will play the snare drum here’, or ‘I want this.’ I just didn’t let him breathe for so long. At some point, he knew what I wanted before I even told him, but in a lot of ways, I was just horrible to Vito, as both a friend and a collaborator.

To go back to a sports analogy, I was a really good baseball player in high school. And he didn’t play baseball. So we’d play whiffle ball in my front yard for six hours straight and I’d beat him like 200 to 3. But he’d still play with me. That’s a good metaphor for the band; I was just really overbearing. There’s a deep respect and love there, obviously, but my plan for the rest of my life with Vito is to not do that shit anymore, to not repeat those patterns I was taught as a kid and ultimately set Vito free from any obligations he has to me.

From what I can tell, he’s really happy. Ever since we got in junior college, he just started getting really good grades and he got super busy. We were both slackers when we were 16, but at some point, he got really good at taking care of himself. I think it was when he started doing kung fu. He just figured shit out and even became more physically confident, because he used to be a little guy that got picked on. But he learned how to fight and it was like, ‘Okay, nobody’s fucking with me anymore.’

In college, he got really good grades and had all of these ambitions to be a filmmaker. I kind of railroaded him into the Rapture. He didn’t really want to be a drummer, but I needed somebody I could trust who was never going to leave my side. And he agreed; it’s not like I forced him into it. I asked him humbly and he accepted. He’s just a very grounded guy, and for a long time I was a very unhinged guy. I was a nice guy, but I was dangerous—like I might say something I didn’t want to say. Vito never says anything he doesn’t mean.

In a lot of ways, I don’t think he knows how to relate to me anymore. It’s like, ‘Who the fuck are you?’ Because I’m super patient now, and really willing to go slow. I’m not trying to force anything and he’s just like, ‘Whoa dude, what’s up with that?’

But that’s exactly why you should work together again: because you’re not that tyrannical person anymore.

For the first time, I’m super open to all of that. I think I just needed to sit in front of a computer screen and listen to ambient loops for a couple of years. Just kind of meditate, and be in a tunnel. And learn how to feel. And be patient. And listen. And not talk all the time.

Have you gravitated more towards ambient music as you get older? Lately, it’s almost like everything from the ‘70s is cool again, whether it’s New Age music or meditation….

Well, that’s fashion—ferns, meditation, and ambient music. Or listening to Planetary Unfolding by Michael Stearns and the first IASOS record. I mean, it’s fashion, but it’s also timely. I’m 43 and have a kid now, but I also still like listening to aggro stuff like Black Flag, Slayer, and the Misfits. That’s fun, but afterwards I just want to listen to ambient music. It’s like they’re two sides of the same coin—a hard left, and a hard right.

Also, being a father, my kid walks around in circles while he’s thinking sometimes. I used to be like that, but I’m not anymore. When you’re responsible for a kid who’s like a ping pong ball or a yo yo, your job is to be still. In a sense, I like a pretty ambient life. When my kid was younger, I needed to sleep when he was sleeping.

Whereas when I was 20, pleasure was getting really wasted, in this ambient space of being high. Now I dream of being in a hotel room with four white walls and clean sheets and nobody there. No screaming kid, no responsibilities—just silence, total deprivation. Also, if you’re going to do traumatic work, you better be able to meditate or have some connection to something bigger than yourself because it’s going to hurt a lot if you’re dealing with unearthing really deep pain. You have to be still, because if you move, it just gets worse and you get more tangled up. You have to slow down when you get older. Your body also starts breaking down. Like I hurt my knee playing softball this year and it didn’t heal for a really long time.

If you hang out with older people, the ones who haven’t dealt with their shit are really grotesque. Time warps you into this knotted, gnarled thing. And the ones who’ve processed whatever they needed to do have aged gracefully. That’s really beautiful.

I remember I had this philosophy professor in junior college who I named my kid’s middle name after. This guy Paul Wheatcroft. He was the first person I ever met that loved himself as a person. He’d come in, sit on the table, take his glasses off, and say, ‘What do you want to know?’ And he’d only talk from his own personal experience. I just loved that guy. I wanted to be like him; that was my life goal. And then I got kind of caught up in music….

For me, music is food. I like to use the analogy of brushing my teeth. If I don’t do it for a few days, it gets weird. People are even more like food than people, though. Who you surround yourself with—even if you’re not talking to them—you eat it. So be careful what you eat.

That sounds like a great sentence to end on, but I gotta ask: What is the status of all the projects you’re working on? Like is the Lucky Blue Eyes thing you’re doing with Barnt and DJ Tennis almost done?

Well I have a label deal with !K7 for distribution, so I’m just kind of figuring out what to put out first. I have a bunch of things, so I want to put my best foot forward first. I also don’t want to rush things. That’s a luxury of having several different projects happening at once. I can press the button when everything’s truly ready.

Lucky Blue Eyes has a visual element I’d really like to work on for a while. I have some solo music, though. That’ll probably be the first thing [through my label]. I’m just taking it how it comes.

You mean a proper solo record, not Meditation Tunnel?

Yeah. At some point, there’ll just be a Luke Jenner record.

Does that excite you, or does it terrify you to some degree—putting yourself out there like that again?

I don’t care. It’s back to that thing of doing everything I wanted to do with music 10 years ago. I worked at record stores and I read a lot of history books, so I wanted to insert myself somewhere in music history—somewhere where you’d have to go through me and my contemporaries if you were a real dork. That happened with “House of Jealous Lovers” and DFA.

Meditation Tunnel is something I made for a very specific group of DJs that I know, who I’m friends with. My goal was to make a record Joakim or Barnt would play. And they do, so that’s cool.

When you interviewed me last time, I was in a really tough place because I had this huge opportunity to make music for the masses in a way. I don’t think I’m ever going to have that opportunity again, and I’m totally cool with that. I don’t need to make music for 14-year-old people who really don’t like music. I was super blessed to have been in that spot at that point in the music industry, where we had tons of money behind us, and this huge manager. I’m really glad I tried that, even though I probably fucked it up. Not probably; I really fucked it up. But it’s okay; it wasn’t supposed to be like that. Life is about whether you enjoy it or not. Everything else doesn’t matter.

I don’t think David Bowie had a better life than me because he reached X amount of people, or left behind a perfect corpse. I mean, I would like to collect more money, because that would give me more freedom. But other than that, my kid knows me and my wife likes me. And I wake up in the morning and don’t feel horribly anxious…. That’s pretty good.

You don’t feel pressured to put stuff out just because you have to—because you have to make money and help support your family?

I’m definitely running out of money. For sure. I made a lot of money, and to the horror of my management and booking agents, I just went, ‘Cool, I have a lot of money in the bank now, so I’m going to just do what I want to do. And what I want to do right now is not be on tour or in a band.’

That’s career suicide—a really bad idea. People were just like, ‘We built up all this momentum and you’re just killing it all.’ Everyone was mad at me; they were all just like, ‘You suck.’ I get why they were mad, but I also wasn’t having a good time. And it’s more important to me how I feel about myself than you being mad at me. So I’m going to just double down on that, and get to know my kid.

My kid is 12, and for seven years now, I’ve been with him every single day. Those years aren’t going to come back. He’s never going to be 7 or 10 again.

That’s awesome though, because you could have not been there, and your son would be looking back at this time and not have any memories with you.

I had this crazy moment with my kid. I was walking him home from this place that has every board game ever made. It was a few summers ago, and we got to the bottom of our street, and we were waiting for the light to change…. He said this really profound thing out of nowhere: ‘Dad, when I was a really little boy, I didn’t know who you were. I knew you were this musician guy and on tour, but I didn’t know who you were. But I do now; I really feel like I know who you are.’

That just floored me; it validated everything I was talking about before. He knows me, and I know him. That’s a big deal.

But he still doesn’t want to listen to dad’s music, right?

He’s quietly proud of me. I remember one time his friend came over, and he told him how his dad had toured all over the world before. And his friend was like, ‘No way. You’re a liar.’ But then he proved that it was true, and his friend couldn’t even conceive somebody’s dad being that guy.

I’m not the kind of person who listens to his own music in the house. Like Prince was famous for only dancing if you put his music on. My kid really likes Black Sabbath a lot. At some point, he figured out that was his favorite band. But he hasn’t really hit that point where music is really important yet.

I think that’s when you find love; there’s a real parallel between romance and music and feeling a lot of stuff. He’s just getting into it. When I was playing music at home a lot, he’d try to mimic me when he was like 3 or something. I have these videos of him messing around with headphones on the computer and checking all the different sounds that you can make. I actually have some really super awesome songs that he made and is intensely embarrassed of. They are amazing. It kind of sounds like the Shags or something like that.

People are always like, ‘Does he play guitar around the house?’ And it’s like, ‘No, he’s not, even though there’s literally 10 guitars in my house.’ I feel like my job as a dad is to show him music, but make sure he doesn’t leave the house hating it.

Well it’s great you’re not pushing music on him like some parents would.

That’s horrible. That’s my dad. My dad turned me into what he wanted me to be. It’s really healing for me to not do that with my kid. I’d rather pull something out of there that’s innate—that’s already there. It’s the same with me moving away from what I think I should be making to sitting still long enough to figure out what’s actually there.

Are you in a good spot with all of the DFA guys now?

James [Murphy] is a weird one. He’s around, but I don’t think he really talks to anybody. He’s become kind of like Morrissey—this legendary dude. Like the last time I saw him, we were standing in the airport, and this professional rugby player from Australia came up to him. And he was literally scared to talk to him, and he had no idea who I was. People are afraid of him. He can’t just do normal stuff anymore.

Most people don’t even know that I know him, and when they find that out, they try to pick my brain. It’s almost like saying that you know the president. He’s at this weird level of being a legend, and will be forever. I remember when I first moved to New York and thought, ‘Bob Dylan was here and Jimi Hendrix.’ Every generation has these people that turn into icons. He’s super into David Bowie, too, so he’s curated this perfect sort of….

An arc.

Absolutely. When I was quitting my band and making bad decisions, he was making the perfect arc [laughs]. Well I don’t think they were bad decisions; they just weren’t publicly satisfying. They were just satisfying to me. My biggest fear was being successful and not being happy with it. I didn’t want to put my head down and trudge through it. That’s what my mom did; she pretended everything was fine until she killed herself.

Well you sound very happy now.

[Laughs] Yeah, I’m happy; that’s true.

Can you tell me a little bit about the new song “Silent Son” that we’re premiering today?

It has a lot of waves in it; like there’s an ocean in the background. I always felt that was my dad’s area of expertise because he was a semi-professional surfer, so I had to just be quiet around him. It’s a weird thing to reference in a dance track, but I was influenced by Kurt Cobain—songs like “Been a Son.” It also feels a little Neil Young-y to me, in how I treated my voice. Maybe I’m reclaiming the ocean in some way. I feel safe at the beach now, but for a while, I felt like I had to be quiet there because I was out of my element.

Isn’t your label named after your time in Hawaii too?

Yeah, it’s the street I grew up on. What I’m trying to do is love my parents. I’m not currently talking to my dad at the moment, even though I love him very much. And my mom committed suicide, so she isn’t around. I do things all the time to honor my parents; I’m really into having them in my daily life.

I think about my dad all the time—every day. I also look more like him every day. And I sound like him; if you spoke to him on the phone, his cadence and tone of voice is identical. My family often doesn’t know who they’re talking to for 10 minutes.

For a long time, I blocked my dad out. I didn’t want to see or talk about him. I didn’t want any reminder of him whatsoever. You know, I didn’t like watching sports or going near water. Now it’s kind of the opposite of that. Now I feel free.