Words LAWRENCE ENGLISH

In 2019, Merzbow enters its fourth decade. This project — created by Tokyo based artist Masami Akita in 1979 — has become one of the most recognizable musical statements of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Merzbow is responsible for a prolific output that is only matched by the amplitude and intensity of the sound itself. Like the music, the mythology surrounding Merzbow has proliferated. His transgressive noise works have become synonymous with tales of extremity and intense affect. Some of these stories are true, and others pure fiction.

Ultimately though it’s his sonic output, a continuum of seemingly infinite and dynamic noise, that has left the heaviest mark. Merzbow has been responsible for influencing wave after wave of musicians and sonic experimentalists, across genres and generations.

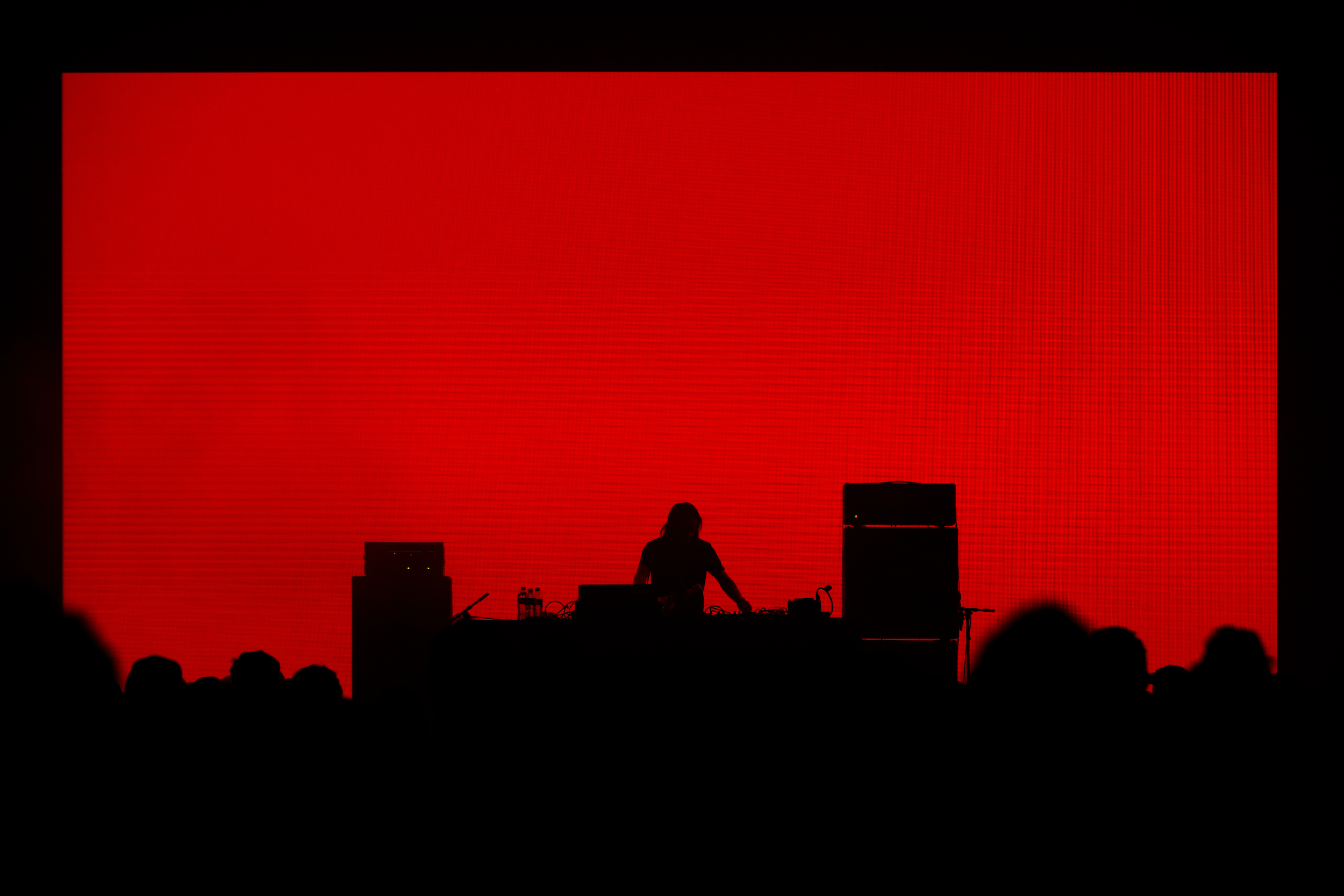

Merzbow is Room40’s guest of honor at this year’s Open Frame festival at Carriageworks in Sydney. On top of the performances he will deliver, I took the passing of Merzbow’s 40th year as an opportunity to better understand Masami Akita’s work.

Over the course of a month, myself and Akita undertook an extended interview which is published on July 12 as a 28-page book that also includes never before seen archival photographs. The book sits alongside Noise Mass, a newly assembled re-examination of materials recorded in 1994. Noise Mass is the sonic tether that cements the transition between his legendary Venereology and Pulse Demon albums.

The following is an extract from this new publication….

The Birth

Lawrence English: I wanted to start by asking about your earliest memories of music and how that led to the emergence of Merzbow in 1979. When you started Merzbow it seemed like an action against virtuosity, a way of fighting the expectations of mainstream music (and other) cultures at that time. What drove you to seek out these sounds and how quickly did you discover the potential of noise during this early period?

Masami Akita: I was part of the generation that grew up listening to rock through the 1960s and 1970s. In primary school I listened to garage and psychedelic pop, what was termed the Japanese Group Sounds — bands like The Tigers and Tempters. From there I started listening to The Monkees, The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. I heard The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper and the Stones’ Their Satanic Majesties Request in real time, so to speak. Then I listened to a lot of what was called new rock and art rock: Jimi Hendrix, Cream, Vanilla Fudge, Iron Butterfly, The Doors, bands like this. After that, I discovered a lot of progressive rock, particularly from records labels like Vertigo. In the early ’70s, Led Zeppelin, UFO, Deep Purple, Yes, Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull, Ten Years After and Grand Funk Railroad all toured in Japan and I would go to every show that I could. That was also the genesis of Japanese rock, and I went to concerts by Japanese bands like Murahachibu, Taj Mahal Travelers, Blues Creation, Flower Travellin’ Band, Miki Curtis & the Samurais, and Flied Egg.

I started playing around 1972, in a studio, with schoolmates from my junior high school. We mainly played blues-rock influenced by Cream and Jimi Hendrix. I was on drums. From around 1973, I began leaning towards improvised music. It was around then that I began playing with Kiyoshi Mizutani. The key influences during that period were King Crimson’s Earthbound, Albert Ayler’s Bells, and The Velvet Underground’s White Light/White Heat. I started listening to more free jazz, free improvised music and contemporary music around the time I was in senior high school. As my band started to play more improvised music, I began rejecting the act of playing, and as in conceptual art, eventually rejecting the act of musical performance altogether.

It was around then that I first heard Pierre Schaeffer’s Symphonie pour un homme seul, and this had tremendous impact on me. I was also quite influenced by Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music, Xenakis’ Electro-Acoustic Music and Walter Marchetti’s Homemade Electric Music, and began producing tape music myself, using only non-instrumental sound = NOISE.

Punk rock came about around 1976, followed by new wave and alternative music, and in that vein there were the industrial bands like Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire and SPK, but I differed from them in that I was creating my tapes using field recordings of sounds I recorded in my environment. The Sony Walkman came out at that time, ushering in a new era of the cassette tape as a primary medium. That’s how I came to make this terribly cheap noise music for cassette tape. Those were the beginnings of Merzbow, around 1979.

On top of music, I had a strong interest in art. My greatest influences were Dadaism and Surrealism. I had read Arthur Rimbaud, Lautréamont, André Breton and Georges Bataille during junior high school. In the 1970s, Surrealism became quite the fad here in Japan, popularized by the literary figure Tatsuhiko Shibusawa and others like him. In my case, literature was my first introduction to this world and gradually it moved into visual art and art theory. At the time we saw other fads like ankoku butoh (the forerunner of butoh) and there was also an occult boom. I conducted some investigations in alchemy and magic myself, in relation to Breton’s theory of magic in art.

Life // Performance

Lawrence: In the late 1980s, Merzbow started to become more recognized outside of Japan. Could you recount your experience of the first concerts you presented in Russia? It must have been an intense way to commence touring outside Japan, and also one that polarised the audience from what I understand.

Masami: In terms of Russia, my first time in the country was in 1988, when I was invited by the Jazz on Amur festival in Khabarovsk, in the former Soviet Union. Kiyoshi Mizutani and I, along with computer musician Kazuo Uehara went to perform from Japan. This was right around the time of the Perestroika reforms under Gorbachev. The Soviets apparently mistook us to be a group that created music with hi-tech equipment, but the only equipment we brought were distortion pedals and other lo-tech gear. We were received very warmly and treated to tours of the war museum and the dwarf circus. We played at two military facilities. During our first concert, we were forced to abort our usual noise performance because the organizers deemed it was not musical. The next day we played with drums and guitar, and our hosts were very happy. A recording of these two nights, Live in USSR, was released on ZSF PRODUKT.

Lawrence: From this point on, touring became more of a focus for you correct? The approach to the live performances on these tours though was more exploratory and site specific.

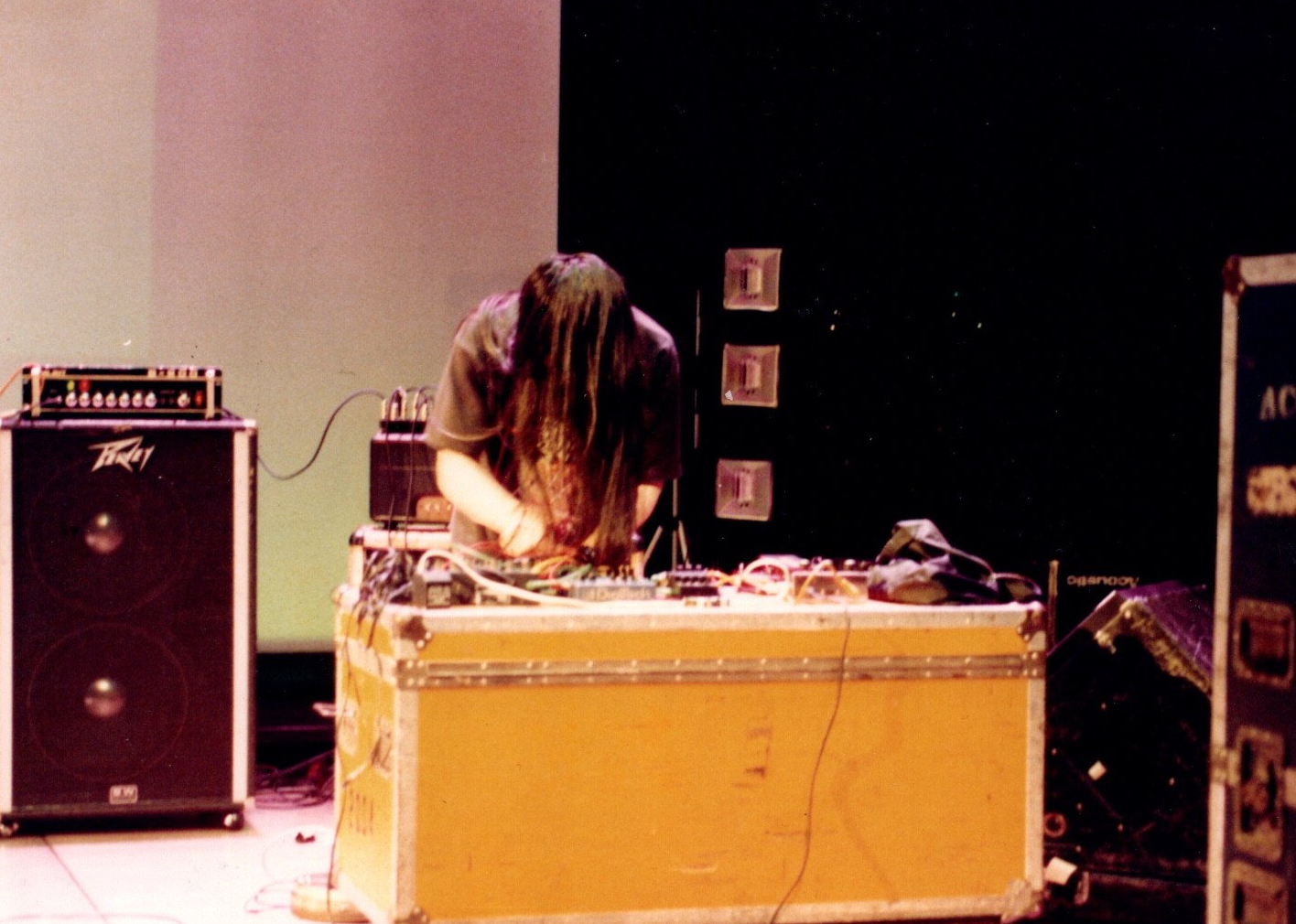

Masami: Yes. Our first European tour was in 1989 and in the United States in 1990. In both Europe and the U.S., I would say that the greatest gains were our encounters and exchanges with local artists, labels and radio stations, as audiences were quite small. The performance style at that time was rather like fieldwork in that we would use found objects at each site. We’d use metal plates to which a contact microphone was attached and played with an iron stick. The contact mic was attached with duct tape, and actually it easily came off during the performance.

It was around then I started performing more here in Japan too, and my equipment and performance styles have since become more established. I also started making the guitar-like self-made instrument with contact microphone during this time. One day, I came across a large quantity of film canisters in a garbage dump at a college where I was performing. I put them together and added improvements, like attaching a jack, as on a guitar, so that the contact mic was secure. The number of effectors grew, and the volume of the music also increased accordingly.

Then and Now

Lawrence: To finish, I’d like to ask you, when you consider your development as an artist over the past four decades, are there particular moments or recordings that in hindsight hold a special resonance for you? What have been these critical moments for the development of your aesthetic approach to noise? What about this work has captivated you and held your attention?

Masami: The music of Merzbow should be viewed as changing, while being part of a continuum. What matters to me is this line of progression, more so than the individual works that comprise it. This is why I continue to make so many new works and release archives of as many of my past recordings as possible.

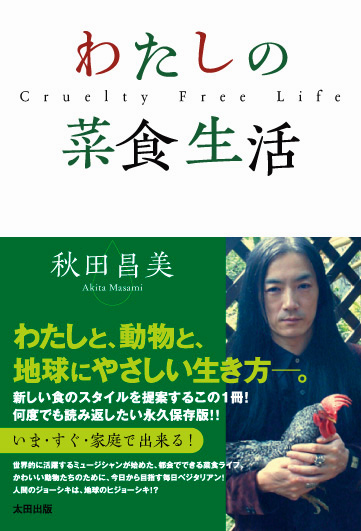

As for critical moments in the development of Merzbow, by chance I started keeping Bantam chickens around 2002 and I got to know these animals and I realised what complex beings they are. Through this encounter, I began giving much thought to meat-eating and why we eat meat. I studied animal rights in great depth. I decided to quit eating meat, then fish, and became vegetarian. I then stopped taking dairy products and using animal products, and eventually became vegan.

I used to drink and smoke, but when I researched alcohol and tobacco production I found that these processes included animal testing, so I completely quit both and I became straight-edge. But straight-edge is more an epithet for the articulation of my intent; it is a confirmation of this new lifestyle, rather than an adoption of that philosophy as such. Though I may assert my vegan position, this in itself is rarely perceived as an opposition to drinking or smoking. But since animal rights are my primary concern, it is essential that I adhere to my convictions in every aspect of life. I suspected it would be difficult to stop eating meat, drinking and smoking without a special reason.

Merzbow has always been about anti-establishment, but grew even more so since 2003 when I became vegan. Merzbow supports the stances of vegan anarchism, anti-livestock, anti-religion, anti-anthropocentrism, anti-economism, anti-commercialism, etc. If people are interested, please read my book Cruelty Free Life.

Special thanks to Haruna Ito for the translation of these conversations. Check out more videos and selections from Merzbow’s back catalogue below….