Words LAWRENCE ENGLISH

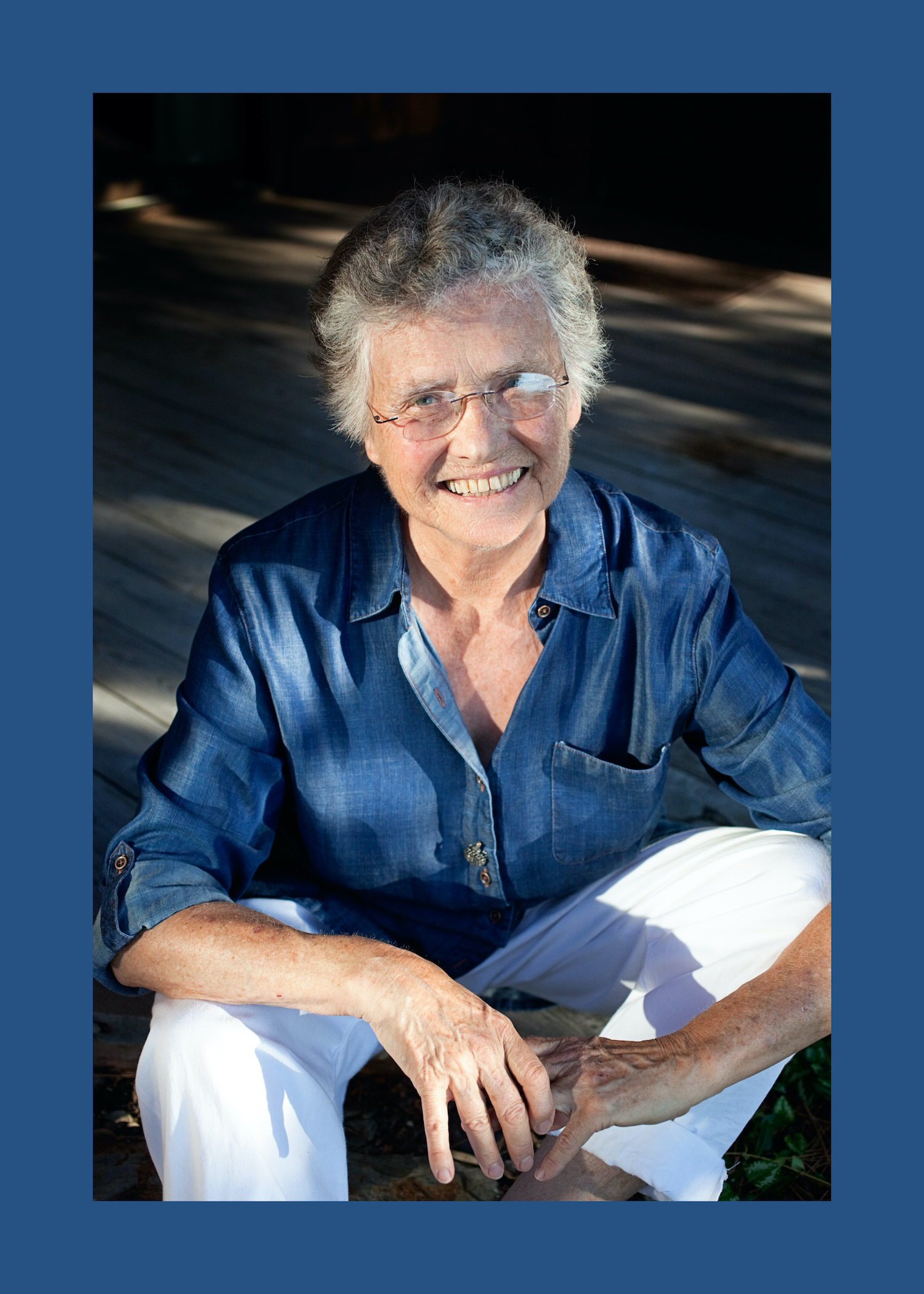

There’s a vibrant energy that surrounds Annea Lockwood. It’s an energy that is created both by her ceaseless curiosity and her openness to the world around her. It’s also, no doubt, the energy responsible for her profoundly diverse and engaging output of the past six decades.

A self-described "water person," much of Annea’s work has been focused on the fluidity of rivers, the vibratory shimmer of oceans and lakes, and the pulsation of waves. It’s from these constant, but never solid forms that she has drawn forth a life’s work that herald equally acts of generous listening, invitational composition and a hunger for considered experimentation.

On the occasion of curating her Wild Energy installation — a work created in collaboration with Bob Bielecki for the Brisbane Festival — I had the opportunity to speak to Annea at length about her work as a listener, composer, and feminist....

There’s a vibrant energy that surrounds Annea Lockwood. It’s an energy that is created both by her ceaseless curiosity and her openness to the world around her. It’s also, no doubt, the energy responsible for her profoundly diverse and engaging output of the past six decades.

A self-described "water person," much of Annea’s work has been focused on the fluidity of rivers, the vibratory shimmer of oceans and lakes, and the pulsation of waves. It’s from these constant, but never solid forms that she has drawn forth a life’s work that herald equally acts of generous listening, invitational composition and a hunger for considered experimentation.

On the occasion of curating her Wild Energy installation — a work created in collaboration with Bob Bielecki for the Brisbane Festival — I had the opportunity to speak to Annea at length about her work as a listener, composer, and feminist....