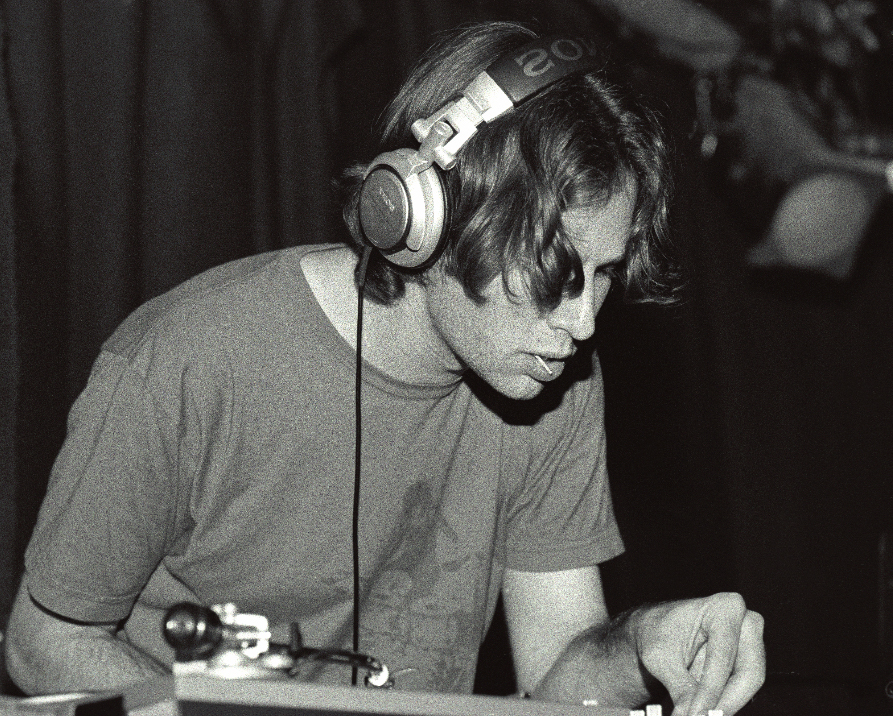

Photo ALEX MASTOON

It’s hard to believe now that loop conductors like Flying Lotus and Four Tet headline festivals and high-cap venues, but the early ’00s was dominated by truly underground tracks within the sprawling hip-hop scene and cutting-edge electronic community. While DJ Shadow and other crate-digging, sample-threading producers broke through to a broader audience on the backs of waning trends like trip-hop and downtempo, difficult-to-pin-down artists like Prefuse 73, Daedelus, and El-P shaped their respective sounds in relative obscurity on such dearly missed imprints as Chocolate Industries, Mush and Definitive Jux.

“Just like skateboarding,” says Zachary Mastoon, “we early beat-makers were a community of weirdos finding ourselves — punks exploring, falling down, scraping our arms and knees — and not too many people gave a shit about it.”

That’s one of the reasons why Mastoon offed his Caural alias in 2009, only to reemerge in recent years with new music for a generation raised on Adult Swim and Low End Theory. Not to mention plenty of social media platforms that cultivate subcultures on the same playing field as pop music.

With his second EP of the year on the way soon (Thank Your Demons, due out September 1 on Caural’s own Prism92 imprint), we asked the Hudson Valley-based producer to share an exclusive mix and look back on his entire career, including his formative years as an jazz musician, Asphodel intern, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles character (no, really)….

Let’s start with a little background. What’s one of your earliest memories of connecting with music on a deeper level?

My earliest memories of music were forged on monolithic IMF speakers my father had set up in our living room. I would sit and stare at the art on these gatefold jackets of whatever vinyl was spinning on the turntable, and it was in this way that the connection between sound and visuals was first made for me. I utterly fell in love with music as this all encompassing, visceral experience.

Was anyone else in your family involved with music or the arts, or did your parents simply have a killer record collection?

My mom was a painter and grew up playing the piano; we had an out-of-tune Gulbransen in between those speakers that I’d bang on as a kid. It was always a running joke in our family that — despite his taste — my audiophile dad was tone deaf. He had been going to jazz sets in his hometown of Chicago since his teens, and my mom brought all types of rock, classical and opera into the mix, so their vinyl collection was eclectic and amazing. Aside from early MTV, the records I grew up listening to were an enormous inspiration for me.

Was Transmission your first proper music project? How did you first cross paths with Stuart Bogie and the rest of that band?

I grew up across the street from Stuart, and he was my first and best friend before I could really walk or talk. When I was 3, my uncle bought me a drum set to piss off my parents, and I had a Casio PT-80 and acoustic guitar when I turned 6. So, as soon as we were able, Stuart and I would record music together in my basement. We called ourselves The Ultraviolets.

From these early tapes on through junior high, it was just the two of us. We did a concert in Joshua “Kit” Clayton’s basement when I was in eighth grade as Stuart and His Neighbor, but Stuart soon met Andrew Kitchen (our drummer) in marching band, who then recruited his friend Eric Perney to quickly learn and play bass.

Transmission (which my mother named as a joke) became a more formal incarnation of our joint musical trajectory.

You guys were skateboard buddies too, right? Can you talk a little bit about how it was a major bridge to discovering everything from punk to hip-hop in the pre-Spotify days?

As kids in the suburbs — especially in the early ’80s — we had no real exposure to hip-hop outside of movies like Beat Street and Breakin’, but skateboarding had small reflections of its spirit; there was movement, visuals (the graphics on the boards, and the imagery in magazines like Thrasher and Transworld), fashion, and a like-minded community exploring an art form.

I knew skaters who liked punk, rap and metal, and I knew skaters who listened to new wave and house. Ultimately, skate culture was less a gateway to certain genres than it was to a sense of belonging. It told us it was okay to be different, and it instilled a fearlessness that informed our lives as artists. After all, you can’t really be afraid to fuck yourself up if you are going to do it right.

Was there any skate video in particular that exposed you to a ton of rad music?

Honestly, it’s funny. I remember watching Bones Brigade (I was 7 years old), but I don’t remember any music.

I do remember Thrashin’ having a Circle Jerks song and an awkward performance by the Red Hot Chili Peppers, but I wasn’t running out to go buy those tapes quite yet.

Did you originally think you were going to be an experimental / jazz musician rather than a solo producer?

When I was really young, I was kinda just hoping to be a guitarist in a rock band. I guess the desire to be a producer sprung from wanting more out of live performance, but the fact is that collaboration always leads to something greater than I could ever dream up myself, especially in jazz and improvisational music.

What was your major at Wesleyan? Studying under Anthony Braxton must have been eye-opening to say the least….

I studied jazz guitar at Wesleyan, but left for NYU about a month into my second semester. Anthony Braxton was beyond influential. His “Materials of Jazz Improvisation” class was crucial for me as an artist, but it was less about his music than his imaginative notation and philosophy.

He was my faculty advisor, and I remember telling him the courses I was planning to take in addition to solo guitar and gamelan orchestra: astronomy, Buddhism, and a class on African-American literature. He looked at me dead in the eyes, laughed, and said, “Wonderful, it’s all music!”

You interned at Asphodel in the late ‘90s — right around the time they were working with everyone from Diamanda Galas to DJ Spooky. What did you take away from that experience on both a creative and professional level? Did it make you want to double down on your own work?

In 1997, I found We’s As Is album at a record store, and it absolutely blew me away; it still does. The fact that the folks at Asphodel saw my gushing email and invited me on board absolutely changed my life. Creatively, working there opened me to the idea of dismissing genre altogether while still maintaining a cohesive sound and approach.

Professionally, I was meeting artists, DJs, and just hearing so much music I wouldn’t have heard otherwise. It was truly another extension of my education, and drove me to start “square-pushing” myself.

Was one of the things you liked about sampling / producing music that it gave you the freedom to be a one-man band in a way?

Oh absolutely. In junior high, I fell in love with the music of My Dad Is Dead, and actually sent him a typewritten letter. At the time, he was doing everything himself, and I asked him how; he actually responded to me! This was in the late ’80s, when my little sampler didn’t yet exist and making records alone was far more expensive and complicated, but his album The Taller You Are, The Shorter You Get showed me it was possible, and I couldn’t wait…

My earliest memory of discovering your music was reading a Turntable Lab recommendation for Stars On My Ceiling in 2002. I feel like that was a very special time — a turning point for turntablism, underground hip-hop, and instrumental beats. In a lot of ways, labels like Chocolate Industries and Mush set the stage for everything from Alpha Pup to Brainfeeder to the club night that brought it all together: Low End Theory. I know this is a complicated, loaded question, but what’s your perspective on that time period and how things evolved between your early albums and Mirrors For Eyes, your last proper Caural LP?

I truly agree that time was special, and it’s more than just my own nostalgia and gratitude for having been a part of it.

When I started using the Yamaha SU700 in 1999, I admit I was being experimental for experimentation’s sake. Listening back now to my first record on Toshoklabs — yeah, it was fucking weird. But I think the more I explored, the more I was able to find my own voice. We all did, and it’s magical that it happened: people using machines to take music apart and rebuild it again had such wildly different results, and spawned so many directions in music.

Being on a label like Chocolate Industries where Prefuse 73 would remix my material, or my name would be next to Souls of Mischeif, Tortoise, El-P or Mos Def? As someone just starting out, I felt I had already made it. And the connection with the Los Angeles scene was immediate for me as well. I was in touch with Teebs on MySpace early on, and Ras G would come to my first shows out there and stand right in front.

Spinning records at Sketchbook (a precursor to Low End Theory) also changed what I wanted to hear, and took my music to a new place. Take (now Sweatson Klank) brought the night to NYC, and he and I would take turns playing the weirdest bangers we could find to sometimes empty rooms. This was not yet popular music!

So, from album to album, there was a natural evolution for me in tandem with the scene itself. I don’t think Mirrors For Eyes is my favorite or even best album, but I can map out how and why I got there.

Why did you decide to largely step away from Caural in 2009? Did it feel like that kind of music had hit its peak on some levels, as new generations began to discover artists through MP3 blogs rather than magazines?

A lot of things were happening simultaneously to be honest. As the sound grew in popularity, the proliferation of new tools to make it — along with the internet to spread it — oversaturated everything. To me, the “beat scene” absolutely peaked and imploded, and everyone started sounding the same.

Personally, I was also feeling limited by the very tool that once gave me so much freedom. With the single exception of “Sorry, Underground Hip-Hop Happened Ten Years Ago,” I was a stubborn dinosaur who rejected the idea of using a computer to continue on. As someone who grew up playing guitar and drums, I needed an instrument to be tactile and real, not colorful, impersonal blocks on a screen.

I was performing on my sampler live along with another Chicago producer named K-Kruz (this material was later compiled as Handmade Evil) but, when it was eventually stolen from my apartment, I was just like, fuck it.

Was Handmade Evila reaction to the digital turn beat-driven music has taken in recent years — a way to show you can make killer tracks with nothing but a Yamaha SU700 and an MPC?

As a perk for a Boy King Islands Kickstarter, I compiled lost demos and alternate takes of songs for our supporters; this collection was released a few years later by Youngbloods as Pastels. Anyway, digging through sketches on my hard drive inspired me to do the same for Caural, but the music that truly stuck out for a coherent release was the last live recordings before things were brought to a close in 2009.

Maybe it was an unintentional fuck you to what I thought I was leaving behind forever, but instead it became a record of a time I’d look back on fondly.

One artist who showed how big this kind of music could be was DJ Shadow. He actually dropped his last record in the style of Endtroducing… (The Private Press) the same year as Stars on My Ceiling. Looking back now, does it feel like heady, sample-driven beats hit a peak around that time in terms of its potential and audience?

Yes and no. I remember Endtroducing… first coming out, and it was wonderful. A lot of those early Mo’ Wax and Ninja Tune records had a clear route from hip-hop instrumentals, but with added freedom to stretch out since they were made without an MC in mind.

The more we got away from loops and appropriating larger motifs from others, the more expansive our possibilities became, but we needed that time to get where we are now.

Before we get into your other projects, I’ve gotta ask: How did you end up landing a voiceover gig for Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles? Are you psyched about the new movie from a nostalgic standpoint since it appears that Seth Rogen grew up with those characters as well?

Haha, oh man. I had done a lot of acting growing up, and when I told my dad I wanted to major in acting at NYU, he said, “What are you going to minor in — ‘Do you want fries with that?’” So, those dreams were dashed for a time.

When I moved back to Brooklyn, a friend of a friend was doing work in cartoons and gave me tips on how to make a demo. I landed a pilot at 4Kids Entertainment that went nowhere, but when I was recording my lines, one of the producers approached me to read for another character on another show. And so I became Dr. Chaplin on Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

To be honest, my sister was more a fan of the half-shelled heroes than I was, but props to Seth Rogen for giving it another life in theaters!

Did you launch Prism92 in 2013 to give yourself more creative freedom and a platform for projects outside Caural?

Prism92 became the de facto imprint for really anything I was doing and releasing myself. Prism was an art gallery where I grew up in Evanston that doubled as an all ages venue for high school bands like mine. It was where we all cut our teeth and sold our tapes, and it was a fertile ground for dreaming. It shut down at the end of 1991, and so in naming my little label Prism92, I meant to symbolize the next phase of those dreams, however they took shape.

Speaking of, what’s the story with Original Ultraviolets? Was it the main collaborative outlet for you and Stuart between the ‘80s and early ‘00s?

So The Ultraviolets was our duo beginning when I was 6, and we had a handful of recordings scattered across cassettes mostly lost or taped over by Bogie’s brother. I also accidentally taped over an entire catalog of our material thanks to auto reverse on a friend’s tape deck….

Anyhow, Transmission enveloped us in high school and continued without me in Ann Arbor and San Francisco with Colin Stetson, but Stuart and I would always mess around with different ideas, including his short-lived Egyptian Brain Surgery project. When I moved back to Brooklyn in 2003, Stuart opened his Williamsburg apartment to me while he was on tour with Antibalas. When he’d drop back in town, we’d press record on new material for fun on a Tascam 8 track, with vocals in the bathroom and any instruments set-up in our cramped railroad living room.

Through Google, we found there was another band called The Ultraviolets, but we were named 20 years before! Thus, The Original Ultraviolets. For its release, I did final mixes years later from the original reel-to-reels, and scoured unmarked cassettes in the Bogie family’s basement for our childhood’s surviving music.

Boy King Islands has a similar back story right — a duo (with Jason Hunt, in this case) with roots that reach back into the ‘90s?

I met Jason in 1991 when he was playing in a different band on the same bill as Transmission. He and his bandmates joined us on horns for our first recording and a handful of shows, but they were really doing their own rock thing. When Transmission left me behind for college – and Jason and his pals kicked out their singer Billy Melody – I stepped in, and we largely did a live hip-hop thing inspired by The Roots.

Years later – after becoming Diverse’s backing band and recording an album that was thankfully shelved – I was living with Jason in Evanston. This was now 2002. Numero Group’s co-founder Rob Sevier was running a small label called Wobblyhead, and approached me about doing a My Bloody Valentine cover for a seven inch series he was putting together. Well, I enlisted Jason on some additional guitar, and that song – “The Girl With The Stained Glass Eyes” – became the first Boy King Islands song.

What made you want to start working on Caural material again?

Honestly I can thank my wife Alex. In many ways, she turned me back into myself.

How did you and Alex meet? When did you start discussing the ideas that would become Word is Bond?

Our story is crazy — you ready? So, I was Busdriver’s touring DJ for a couple of years and, as was customary at the time, I was his top MySpace friend. Well, Alex’s brother told her to check him out cause we were soon gonna play Miami with Deerhoof and Harlem Shakes. In doing so, she saw my photo, and added me. This was late 2006.

The venue for the performance changed and we never met, but years later, I saw her on a little MySpace status feed and reached out. This began a digital courtship that turned into a long-distance relationship, a couple breakups, and a magical marriage.

We began collaborating on videos a couple years in, but Word Is Bond was entirely her baby. I stepped in to help with the screenplay, ghost-write raps, produce, cast and compose.

Is homophobia something you witnessed firsthand throughout your years as a producer, and a big reason why you felt the need to help tell that story?

As a heterosexual cis male growing up in the ’80s, homophobia was nothing but normalized. The “f” word was casually tossed around in movies; people played a game called “smear the queer” in elementary school; I knew absolutely no one until college who came out; and frankly I had never been exposed to anything outside of my standard vanilla crushes on girls.

As I grew up, luckily my eyes opened wider, and suddenly I was like, “Woah, none of this is cool.” Whether it was on the screen, on the radio, or in person, the utter machismo “no homo” bullshit became such an ignorant and unfunny joke, and now the veil has been removed on so much more of the hatred driving us apart.

Alex’s brother and many of her friends are in the LGBTQ+ community and, as her partner, I was happy to support both her vision in bringing their stories to life, and strengthening my own empathy as an ally.

Did working on Word is Bond — seeing how well Alex’s visual language melded with your music — lead to your work on “Us in Octaves”?

A: Alex and I do nearly everything together. We used to butt heads a little more when we met thirteen years ago, but now we may as well share a brain. So, when she had an idea for another music video for me, it was an immediate yes.

What’s the back story behind “Us in Octaves”, the two-part music video you’re unveiling soon?

When we left Los Angeles in 2019, we were working full-time in film in the Hudson Valley. I finally had time to return to music late that fall, and “Ceremony” was the first song I finished. We met a dancer at a screening of Word Is Bond in Harlem, and he and his friend were the original two man cast set to shoot in March of 2020. We all know what happened then.

Two years later, when we escaped upstate New York and were ready to revisit the idea, everything changed. She and I brought on a fantastic DP named Jaan Utno who worked with us as a gaffer on Word Is Bond and, in the casting process, she found muses in Madison Wada and Robyn Ayers.

Our shot list was enormous, and it was the most art department-heavy project we did together. So when she started editing, it naturally became a two-part story: there was just too much to say.

Are you planning on doing a full movie together at some point?

I am already helping her develop a feature script…. Stay tuned!

Dakou sounds like a natural progression of your work as Caural and a live musician. Did it feel like dipping your toes back into a world you sorely missed, making another EP (Thank Your Demons) come together even more naturally?

Thank you! Dakou, Thank Your Demons, and material I am working on now for a full length next year all feel like I have picked up where I left off, but as a fuller and changed person. All along, I had been relegating styles and even instruments to different projects and aliases. Maybe because I feared they wouldn’t fit together?

Whatever the case, in returning to music — honestly through Alex kindly forcing me to soundtrack Word Is Bond — I realized that my sound is less a style to put in a box than it is me using everything I have to articulate whatever comes through me.

You also released a digital version of your remix compilation last month. Does that feel like the final word on a very specific period of your solo career?

Oh yes! Remix Tape — also released as a limited cassette — compiles almost all of the remixes I made between 2003 and 2008. I left off an embarrassing one unknowingly done at the wrong speed for Miho Hatori, but most everything else that wasn’t already stolen for another one of my releases made the cut.

A lot of energy went into these works and often pulled me away from my own material, so in hindsight this collection feels like a lost album.

What can we expect from you next? Is another solo album on the way at some point, or are you more interested in pursuing a film composer path right now?

A little bit of both to be honest. Life has constantly pulled me in different directions, and I have always gone towards what feels best. I am finishing a sound mix on a short documentary right now, and am eager to get back to work on my next album. I will say that I’ve become a lot more intimately involved with the art around my music lately, so I aim to continue more of a multi-disciplinary approach to any and all of this.

Let’s say someone has never heard your music before. What are five tracks that best represent the range of your work as both a solo and collaborative artist, and why?

1. Caural, “Sorry, Underground Hip Hop Happened Ten Years Ago”

This exercise in OCD levels of organization and collage got me invited to a speaking engagement at Princeton (woo!), and was the craziest shit I have ever done. Like, ever. I took well over 400 samples of the word “yo” from across my rap albums, and spent a couple of months painstakingly building each Frankenstein measure of the song. All of my music as Caural involves intense sound editing, organization, and collage, but this piece is really a broken magnifying glass held to my process.

2. Caural, “Transition Suite Part 2: Papillon”

A tune I made with the dueling saxophones of Stuart Bogie and Colin Stetson for Mirrors For Eyes. I’ve always loved the way this turned out. It feels live, and was also one of the few times I used my own electric guitar on a Caural track.

3. Boy King Islands, “I Talk To The Wind”

I worked at a second record label in the early 2000s: Coup D’Etat (J-Live, Paul Barman, Rasco, etc.). My then boss, Howard Wulkan, asked me to watch his cat Pokey in his Manhattan duplex one weekend. He had a studio in the basement, and I cranked out the vocals, guitars and bass for this tune in a day; I recorded the drums back in Chicago, and Jason’s wife Beth played the almost imperceptible Rhodes. It’s one of my favorite (mostly) solo things I’ve done in the rock realm, and I’m embarrassed to admit that – until hearing King Crimson’s original – I thought that Opus 3 wrote this song.

4. Caural, “Clear Vinyl”

Still one of my most streamed songs 20 years later, likely because of its inclusion in a skate video backing the street skate pioneer Rodney Mullen. I loved making this rock song out of almost entirely shoegaze samples. It snaps, if I do say so myself.

5. Caural, “Enneagram”

I still love drum & bass. When I was touring with Busdriver, I played a version of his song “Wormholes” in double-time with the famous Amen break (if you don’t know it, it’s basically the electric guitar to the rock music of jungle). Enneagram – a completely live, improvised drum & bass tune in this spirit – stands out for me as an example of the hardware sampler as a live instrument.

Finally, tell us about the “Holograms” mix you made for us. In a lot of ways, it feels like a reflection of everything we just discussed — a full-circle journey of someone who’s been greatly impacted by music on a personal and creative level for decades….

In curating “Holograms” — almost all imaginary collaborations meant in some cases to be slightly absurd — I joined together main themes from my so-far two releases this year. The first — from the spirit of Dakou (“cut out”) — was to highlight inspirations of mine: crate-dug gems I wanted to place within a framework of hip-hop. I have found there are such through lines connecting grooves across genres, and for someone to stumble across mangled cassettes with no context of their history or culture — as was the case in China that spawned the title Dakou — music presents itself as itself, leaving the listener to draw their own connections.

The second theme came from Remix Tape, and from that time in my musical life. Some of these tracks were on constant rotation in my early DJ sets, while others were ideas never brought to fruition — either by me, or in some cases by colleagues of mine. But in layering them with acapellas, I also wanted to give a nod to the mashup: an enormous fad of the time which was fun and endearing while simultaneously just kinda horrible. But in a positive light, I think of remixes themselves as holograms: the meshing of waves (in this case, sound) creating a version of the object impossible without the other.

Music is math, isn’t it?

TRACKLISTING:

1. We – Flutesque – Incursions In Illbient (Asphodel)

1. 1991 – High-End – High Tech High Life (Opal Tapes)

1. (Christian Ministry Truck Stop Tape Intro)

1. Miles Davis – Gingerbread Boy – Miles Smiles (Columbia)

1/2. Aaliyah – Rock The Boat (Acapella) – Aaliyah (Blackground Records)

2. GB – The Roman numeral 3 – Absence of Color Phase I & II (Sound In Color)

3. Dimlite – Last Repetitions Piece/Lorraine For The World – Cookie & Brownie EP 3 (Astrolab)

3. Beastie Boys – Body Movin’ (Acapella) – Hello Nasty (Capitol)

3. (Excerpt from Dirty Thoughts – Documentary)

4. Slum Village – Look of Love – Fantastic Vol. 1 (Counterflow)

5. Dabrye – Hyped Up Plus Tax (Outputmessage Remix) – Payback (Ghostly)

6. Painted Cakes – Moving On – Painted Cakes (Self-Released)

7. Push Button Objects – 360 Degrees (Beatapella) – 360 Degrees Remixes (Chocolate Industries)

7. Clipse – Wamp Wamp (What It Do) (Acapella) – Wamp Wamp (What It Do) (Star Trak Entertainment)

7. Herbie Hancock – Sleeping Giant – Crossings (Warner Bros)

8. Ammoncontact – Let The Rhythm Mysticism – Dublab Presents: In The Loop 3 (Plug Research)

8. Ford & Lopatin featuring Tamaryn – Flying Dream (Acapella) – Snakes/Flying Dream (Mexican Summer)

9. Ramsey Lewis – My Love For You – Funky Serenity (Columbia)

9. Opus 3 – It’s A Fine Day (Acapella) – It’s A Fine Day (PWL International)

10. Kutmah – Warm Like The Sunshine – Warm Like The Sunshine (Poo-Bah Records)

11. Knxwledge – thedaysbefore – Buttrskotch (Leaving Records)

11. Stevie Wonder – Tuesday Heartbreak – Talking Book (Motown)

12. Danny Breaks – The Jellyfish – Another Dimension (Alphabet Zoo)

12. Missy Elliot – Get Ur Freak On (Acapella) – Get Ur Freak On (Elekrtra)

13. Collin Walcott – Prancing – Cloud Dance (ECM)

13. Nas – It Aint’ Hard To Tell (Acapella) – It Ain’t Hard To Tell (Columbia)

13. Kraftwerk – The Robots – Man Machine (Capitol)

14. Sea Level – Midnight Pass – Cats On The Coast (Capricorn Records)

14. Quincy Jones – Midnight Soul Patrol – I Heard That!! (A&M Records)

15. Diverse featuring Lyrics Born – Explosive (Caural Remix – Instrumental Version) – Remix Tape (2003 – 2008) (Prism92)

15. Mobb Deep – Shook Ones Pt. 2 (Acapella) – Shook Ones Pt. 2 (Loud Records)

16. (Excerpt from Busdriver live at Irving Plaza – unreleased)

16. John Klemmer – Poem Painter – Barefoot Ballet (ABC Records)

17. Caural – One Day It’ll All Make Cents (unreleased)

18. Jean Luc-Ponty – Imaginary Voyage Part IV – Imaginary Voyage (Atlantic Records)

19. K-Kruz – Slip Away – Time EP (Organik Recordings)

19. Mos Def – Mathematics (Acapella) – Ms. Fat Booty / Mathematics (Rawkus Records)

20. Sweatson Klank – Not The Same – Collage Dropout (Self-Released)

21. Jeff Beck – The Golden Road – There And Back (Sony)