The following story originally ran in our ill-fated iPad ‘magazine’. (Remember those?) We’d love to run more long reads like it, but need your support now that most ad dollars are devoted to Facebook. Please donate via PayPal here to keep us kicking, algorithms be damned.

Interview J. BENNETT Photography DAVID CORTES

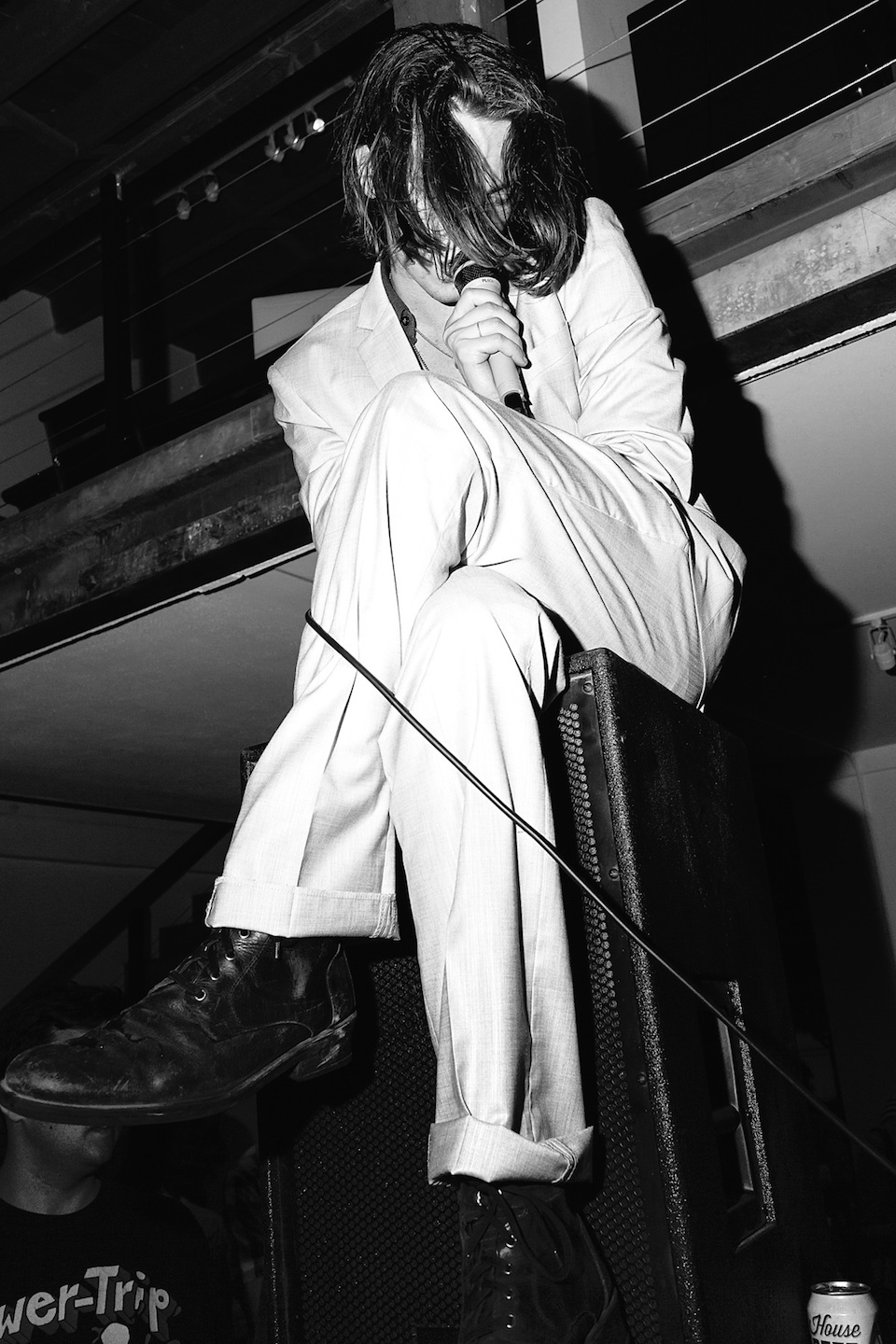

“The first time we came to the States we went on a long tour,” says Iceage singer Elias Bender Rønnenfelt, “and there were all these kids kicking each other in the face while we were playing. I talked to them afterwards, and I realized they were just getting off on fast drumming and loud guitars. That was very frustrating, because I came here to communicate something but they didn’t understand it.”

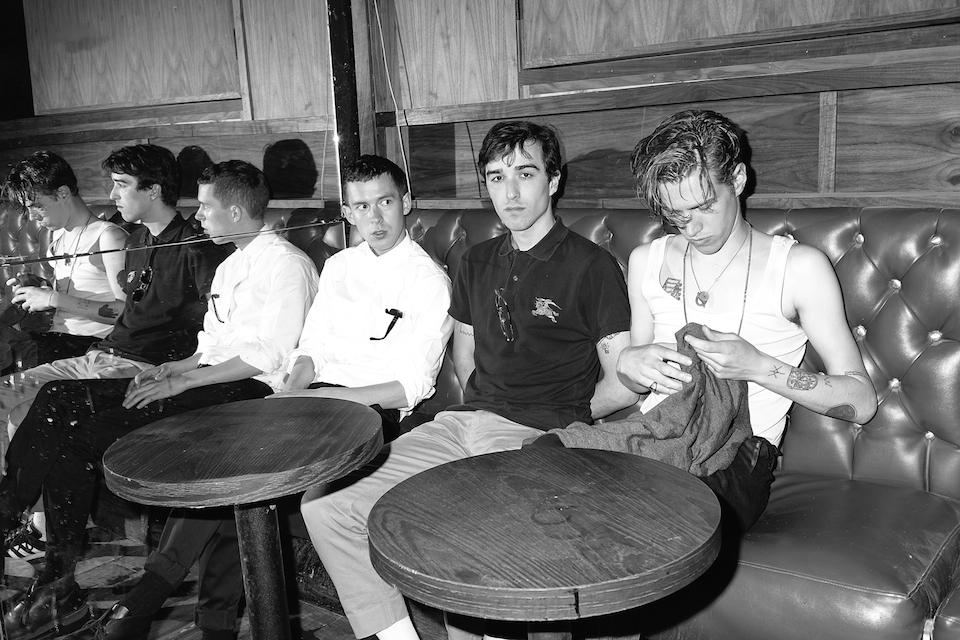

Three years and one Matador-endorsed album (last year’s You’re Nothing LP) later, Iceage is still considered a band you bust heads to, which Rønnenfelt doesn’t mind as much the general lack of engagement with what he’s actually saying beyond all the blurry rhythms and pressure-cooked riffs. Or as Rønnenfelt’s longtime friend and collaborator (see: Croatian Amor, Vår) Loke Rahbek puts it during our roundtable discussion at LA’s now-defunct Church on York, “There is this striving for hope in what all of us do. I don’t find it nihilistic or overly negative. It’s very much about beauty, but beauty comes in many different shapes.”

“It can be destructive,” adds Lower drummer Anton Rothstein, who also hammered out beats in Rahbek’s hardcore band Sexdrome. One of the reasons this all sounds so damn incestuous is the record label/shop Posh Isolation. Run by Rahbek and his Damien Dubrovnik bandmate Christian Stadsgaard, it’s the one clubhouse these particular Danes—and one chain-smoking, largely silent Swede, Lust For Youth frontman Hannes Norrvide—proudly belong to. That’s why they’re all here: because Rahbek asked their bands and lesser known, semi-related acts like Age Coin and Puce Mary to represent the Posh Isolation roster at an LA showcase called “13 Torches For a Burn.”

Taken together, Rahbek, Rothstein, Rønnenfelt and Norrvide are not the imposing presence they project onstage in varying degrees of menace and melancholy; they’re happy to address our countless questions and concerns over the course of an hour-long conversation, even the one about why Copenhagen is not, in fact, the “happiest place on earth”…

Much has been made of the fact that you’re from Denmark. Is it an important factor in what you do?

Elias Rønnenfelt : I wouldn’t judge myself too much as a Danish artist or in a Danish context. I’m an individual, and I don’t feel any shared connection, generally, with Scandinavian musicians or people. We come from a pretty close-knit environment, and that’s not any more typical for Denmark or Scandinavia or France. Of course there’s social heritage and stuff, but that doesn’t play too much of a part in what we’re doing.

Do any of you feel like what you do is uniquely Danish?

Anton Rothstein: Most of the hype about what we do is just made out of people’s imaginations. We’re just friends who do what we do. Friends play football together, they go out together, maybe they play music together—and that’s what we do. I don’t consider us unique or anything. We act in the moment and do what comes naturally.

Elias: But to answer your question, if I had been born in Hungary, I think my art would not be so much different. My conditions would, but the artistic output comes from somewhere else.

Loke Rahbek: I think you are colored by your climate to some extent. It’s difficult, because at the same time it would be a lie to call what we do “typically Danish.”

Elias: We take things from our environment, of course, but now we’re here in Los Angeles and that will color us in some way as well. It’s pretty international now.

Loke: Yeah, everyone is traveling all the time now. So even though we are Danish, we are also something else.

“I’m not interested in me as an 18-year old anymore.

I’m somewhere else.”

Your lyrics are in English. Does that come from some need to communicate with the outside world? Or is it just that Danish is too limiting?

Elias: It wasn’t that much of a statement. We just started writing in English. When you read books in English or listen to records where they sing in English, English becomes this language for poetry. Danish is more for communication.

Anton: That’s true. I think that has to do with heritage and how you are raised, with TV and radio and also with the Internet. You’re forced into this English world. We don’t use English out of some need to conquer. We are not out for the rock ‘n’ roll dream.

Elias: When I started writing in English, I never imagined anyone over here would ever hear it.

Hannes Norrvide: It’s also easier to write in English, I would say. If I were to write in my native language, the lyrics would have to be so much better. You get more distance from English, because Swedish for me would be more revealing.

If Copenhagen only links you geographically, what links you artistically? Presumably, you have similar ideas.

Loke: I think that’s the connection—less of a sound and more of an idea that is overlapping in different projects.

Elias: Yes, the country is not as important as us being collective minds feeding off each other.

Anton: That was obvious on the Rosehip, Scallop, Dancer compilation Posh Isolation released not long ago. Almost every band played differently, but there was an idea that was obvious in all the songs.

Loke: We share, if not a language, then at least a dialect. It’s like if women stay in the same place long enough, their periods start to line up.

So you’re all having your periods at the same time?

Elias: That’s your headline for the article!

What kind of artistic philosophies do you share?

Loke: I think it’s dangerous to talk about that, maybe, because it’s a fragile thing. I’m afraid if we dissected it, maybe it would disappear.

Elias: When it comes to music, what needs to be there is immediacy. I think we can all agree that it can’t be overthought—it has to be immediate.

Anton: Yeah, it’s all about intuition and gut feeling. As I said, acting in the moment.

Loke: If we went into it too much, it would be like when you see a magic trick and then they show you how it’s done.

So you don’t want to demystify it?

Elias: We don’t even know the truth, I think. It’s an answer we can’t give.

You mentioned immediacy. What else do you value in music?

Elias: Honesty.

Anton : Urgency.

Loke : Bravery is a good word too, I think. It’s an environment where there’s so many different genres of music and there’s an eagerness to experiment and learn. We don’t want to fall in the trap of thinking you’re the master of one field. The fact that we sit in rooms next to each other and someone is working on techno and someone is working on a sound-art piece and someone else is doing punk—and then you switch—that’s a very important part of the process. You have to stay open and stay experimenting.

Elias : After five years or so, no one has settled anywhere. Everyone is constantly evolving.

Loke : Once you stop doing that, you should stop making music.

Anton : Stagnancy is for the lazy and unwilling.

Immediacy is a good word for what you all do. Do you think that makes your music “of the moment”?

Elias: It’s a photograph of a moment.

Anton: I think it’s very modern.

Do you ever think about creating something that’s timeless?

Elias: No.

Anton: I don’t think so. I think it’s kind of hard to think of your own stuff that way.

Elias : Maybe universal is a better word.

Anton : It’s the horizontal view, not the vertical. You don’t want to do something that’s locked in place.

Elias : You want a basic human feeling that’s universal.

Anton : Timeless is also a word a reviewer would use. A song is only what people make of it. You can’t think of making an epic masterpiece.

What I’m talking about is the music you’ve already created, that’s already out in the world. Do you hope that people will still be listening to it in 50 years?

Loke: I hope they come up with something much more wild in 50 years. For us—this collective or group of people—it’s always about moving forward. Don’t get into the mindset of ‘Oh, I made a record,’ or ‘I did this.’ You did something, but what will you next? It’s a ridiculous thing to sit here and try to romanticize our legacy.

Anton: That’s very obvious with Iceage, I think. They release a record, and then they play maybe one song off of it when they start playing shows, and the rest is newer songs. That’s a good picture of striving forward.

I’ve spoken with musicians who feel their music belongs to them while they’re recording it, but as soon as it’s released, it belongs to everyone else. How do you feel about that?

Elias: I don’t feel that connected to previous Iceage records. One is a picture of me as an 18-year old. People can tap into that if they want, but I’m not interested in me as an 18-year old anymore. I’m somewhere else.

Loke : I can definitely recognize the… not disconnect, but this feeling that once you’re done with it, it’s in the past. And I think that’s why it’s such a difficult question to answer.

Elias : I can’t listen back to something I did years ago because it’s like reading old diaries. It’s a horrible feeling. But I’m glad it’s there.

Lust For Youth is a good way to describe what’s happening with you right now. You’re all young, good-looking, and getting lots of attention. But at some point maybe that attention will go away. Have you given much thought to that?

Loke: There was no attention for a very long time, and I wasn’t sad about that. When Iceage and me and Anton’s old band, Sexdrome, became friends, I think we realized that if we put the two bands together and the friends around it, that was enough people to have a good show. If their friends came and our friends came, there was a crowd. And if that were to happen again, I would be fine with that.

Elias : I think we all do this because we need to be doing it. Attention or not, we still have to carry on.

Anton : There’s never been a goal, so the attention doesn’t matter. I’ve met other Danish bands whose biggest goal is to play this main festival in Denmark. They strive for success and radio play.

Loke : This classic idea of ‘making it,’ what does it even mean? When I’ve created something that makes sense, I’ve ‘made it.’ But it’s not about how many pictures there are of me in a magazine.

Elias: If I play a concert, I need to release something to be satisfied… Whether 1,000 people or 20 are witness, the theory is still the same.

Anton: In Lower, we also talk about satisfying our own personal needs.

Loke: Any form of creation is essentially an egocentric process. There’s a fantastic quote from Philip Guston, the painter. He’s explaining that he’s reading the newspaper in the morning, reading about all these tragedies. And then he goes to make a painting to get all these tragedies out. And really what he does is he goes to his studio and worries about what kind of glue he should use for his frames. I think that’s very honest: It’s very much about you and your obsessions. It’s never about anything but that, and it shouldn’t be.

“The great truths are usually

found in books, not records.”

Does having a larger audience make you want to communicate things differently?

Loke: No, but of course it’s interesting. If you’re working in underground culture, you’re often preaching to the choir. When you get beyond that, you have experiences where you think ‘people don’t know the foundation of this.’ That’s when you have a chance to make people realize there are other worlds they can tap into. That’s a very rewarding feeling: when you realize your audience doesn’t have the same record collection [or] read the same books, and yet they can still learn or feel something from what you do.

Elias: All this being said, I feel good about the attention because I feel they should be paying attention. Because it’s relevant.

Anton : People perceive music in different ways. Not everyone listens to the lyrics. Some people like throbbing beats. Some people just don’t care. As a drummer, I don’t write the lyrics, so if someone said they liked our music [but didn’t understand the lyrics], I would be satisfied.

Your bands seem to be more popular outside of Denmark than in it. Why do you think that is?

Elias : We have a following in Denmark, but it’s mostly ourselves [ laughs].

Anton: Denmark is really small. It’s four hours by train from one end to the other. Copenhagen is the only place where there’s been something going on for the last 20 years… If Lower did a tour of smaller cities, there’d be maybe five people at the shows.

Elias : Iceage has played the three main cities in Denmark, but we tried going to a small fishermen’s town, and we played to one guy.

Loke : At the same time, I do find what we do to be weird, experimental music. I think there’s a limited audience for that anywhere.

Elias : It appeals to maybe 1-percent of the people in any city. Los Angeles is a bigger city, so that 1-percent is bigger here.

Denmark’s been called the “happiest place in the world”, and yet much of the music you play is angry. Could the Internet be wrong?

Elias: [Laughs] That’s just bullshit.

Anton: How the fuck do they decide if we are happy or not? In Denmark, if you are the least bit frustrated with your life, you get prescription pills. It’s turning into a mini-Xanax country.

Those pills are very popular here as well. But Denmark has a high standard of living, doesn’t it?

Elias : It’s very comfortable—our conditions are good, and it’s very hard to end on the street.

Anton : But is being comfortable the pursuit of happiness?

Loke : Everyone defines happiness in different ways. Some people are happy when they get chained up and pissed on. Some people are happy when they eat dinner with their parents. Some people are happy when they do coke. Some people are happy when they go to church. So we’d have to define happiness. Is it having a comfortable bed and knowing that if you get fired, you’ll get payments from the government?

Anton: When you enter the Copenhagen airport, there’s a big Coca-Cola advertisement saying, ‘Welcome to the happiest place on earth.’ It’s a slogan, a tourist trap.

Are you railing against that in any way?

Elias : No. I mean, do you think about the American Dream every day?

Well it’s hard to avoid because it’s such a huge lie .

Elias: You have a cooler catchphrase anyway.

Anton : We don’t have a brand like that.

Loke : Wasn’t it Oprah who came up with the idea that Danish people are so happy? Maybe that’s the problem—it’s an American concept some graphic designer from the Danish tourist bureau grabbed onto.

Do you ever read articles about your projects?

Elias: Occasionally, when I stumble on them.

Anton: I usually stop after the first paragraph says something like ‘experimental punks from Copenhagen.’

Loke : It rarely helps the work. The performances and releases are a much stronger language than us chit-chatting. Reading articles about yourself is strange.

Elias : If you’re dumb enough to read a good review and believe [it], then you have to believe the bad ones, too. Usually if it’s a bad review, the guy is an idiot. But if it’s a good review, he’s also an idiot. Occasionally you’ll find a guy who is onto something.

Anton : I recently read a review of a half-assed show we did. We had a weird feeling about it afterwards, but this guy praised it to the heavens. How can you take that seriously?

Elias: People who would spend their life being a music critic are probably not too smart anyway.

Is the interview process a necessary evil?

Elias: I don’t like interviews, but that’s because 99-percent of the journalists are unprepared or don’t seem to have any actual interest in the band. But I can see that you are motivated and interested, therefore I am motivated and interested.

Anton : We had a group interview like this for another magazine, and the questions were like, ‘What’s your favorite color?’

Loke : This idea that if you’re good at one thing you’re automatically good at another—because we make brilliant music we should have an opinion on politics or the newest fashion designer—doesn’t make sense.

And yet many musicians relish the opportunity to talk about things like that.

Loke: The great truths are usually found in books, not records… Somebody said art is something that you can’t write down or print on a T-shirt. Again, it’s about universal languages and tapping into something that feels true.

“I think that’s what we’re doing—

fucking till the end of the world.”

What are the biggest misconceptions about what you do?

Elias: People that get off on the aesthetics but don’t feel the content.

Anton: People take major music outlets for granted. For instance, if Pitchfork writes that we are ‘depressed, anxiety-ridden teenagers from the dark concrete jungle of Copenhagen,’ it’s just not true. People try to force some emotion onto us that’s not there. Every release on Posh Isolation will be reviewed like, ‘his dark Ian Curtis-like voice’ or something like that.

Elias : There’s a belief that this music and aesthetic is not a dead place. There’s still new things to be found. We’re finding them every month.

Loke : Occasionally things get put in the wrong box but at the end of the day it doesn’t matter. Anyone willing to engage with it will figure it out eventually.

Hannes, do you agree or disagree with any of this? You haven’t said much.

Hannes : Everything is nice.

Are you not a big fan of interviews either?

Hannes: No, it’s just that I have a hard time explaining things. It’s more about emotions.

What do you aspire to with your music?

Elias: I’m aspiring to become a pop star. [Laughs] But really I hope to find myself as a 45 or 50-year-old man being able to communicate the feelings that come with that, and being able to paint the perfect picture of that time.

Does your music mean something different to you now than when you were just playing for your friends?

Elias: I think everything has turned out as it’s supposed to be… Not in a spiritual way, but things go as they should and I have trust they will keep doing that.

Loke : In some ways I’m not surprised that people got it… Because it’s beautiful. It’s probably the best music that exists right now. And that being said, it’s still coming. You could look at it like intercourse, and the orgasm is far from now. Sometimes in the best sex, you never have an orgasm. And I think that’s what we’re doing. We’re fucking till the end of the world.

A few months after our interview, Iceage shared a new single. It is not a song you bust heads to. Stream it below, along with other key releases and videos from Posh Isolation’s extended family…