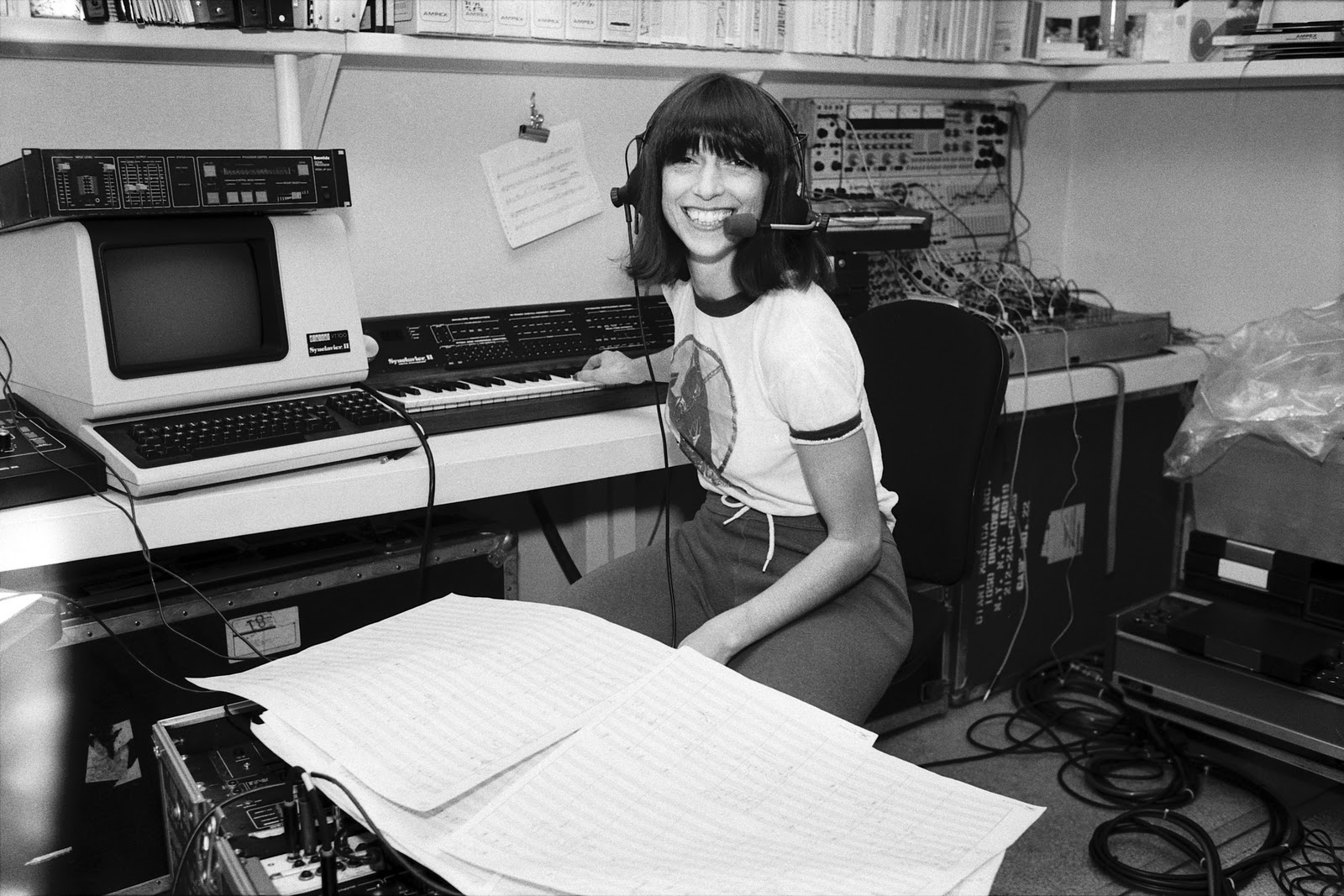

“The frustration was with the philosophy of the instrument,” says Suzanne Ciani, when we ask her why she gave up her beloved Buchla synthesizer decades ago to pursue a career in piano-driven New Age music. “When it broke down, I would break down. I had to wean myself from it just to survive. I had to have interventions. People would say, ‘You’ve got to do something else.’ So that was part of it—being too dependent on this thing I couldn’t count on.”

Ciani also had to deal with being far too ahead of the curve as she embraced the possibilities of electronic music and moved away from her classical background. When she studied Music Composition as a graduate student at Berkeley in the late ’60s and made the switch to synth-based work, the concept was still foreign to most technicians and fellow musicians. Especially with the Buchla, an instrument that lacked the tactile keyboard components Robert Moog’s instruments had.

“It had to go all the way out to the west coast and come all the way back to the east coast every time it needed to be fixed,” explains Ciani. “And if it made it one trip, it wouldn’t make the other. Then somebody stole half of it. I found out about that 20 years later, when someone sent me a photograph and said, ‘Does this look familiar to you?’ I nearly fainted.”

Another reason the composer/performer has had to steady herself in recent years is the relative success of Lixiviation, a Finders Keepers compilation of the experimental logos, segues and compositions—including gigs for Coca Cola, Atari and a pinball machine named Xenon—Ciani wrote and recorded during the height of her love affair with modular synthesis. When label owner Andy Votel originally reached out to Ciani about revisiting her archives, it took her two years to even let the idea sink in.

“I thought, ‘Really?'” she says. “And now my ears are awakening again, just because I’m part of the zeitgeist of contemporary whatever. Even though I’m in this remote place, I get it.”

Ciani spoke to us from her seaside home an hour outside San Francisco, where she’s lived since the early ’90s. She performs with Votel and Sean Canty (Demdike Stare) at Lincoln Center’s David Rubenstein Atrium tonight, as part of Unsound’s New York festival…

It must be strange for you to return to New York after all these years since you lived there for quite a while. What neighborhood did you stay in when you first came here?

Soho before it was Soho.

When it was full of artist lofts?

Yeah. There were no cabs or anything there. It was quiet. It’s so different now it’s unbelievable; it’s like Disney World.

How often do you visit? Only when you have work to do?

Well, I love New York. I live now on the ocean, with the sound of the waves lapping at my feet. It’s what I dreamed of when I was sleepless in the big city, you know? But as breathtakingly beautiful as this is, the energy is one-dimensional, kinda. It’s the slow kind. I’ve always loved the energy in New York. I need to go back to get refueled.

Have you lived in the same California home since the early ’90s or have you moved around a bit?

I’ve been right here. I came to this house for one year in 1992 and I never left. I do travel a lot, and I spend a good amount of that time in Italy, so I use this as a base. But yeah, I’ve lived here longer than I can imagine.

Did you have to do a lot of work on the house over the years?

I try not to undo some of the natural, traditional qualities of the house because the aesthetic of Bolinas is kinda decay, you know? I guess I’ve done a lot but it’s still pretty funky.

Where did you end up living in New York once you got settled there in the ’70s?

I was at 40 Park Avenue, in a quiet little neighborhood with the Empire State Building right over my terrace. And then I bought the studio on 23rd St. I thought of moving but in those days, all of the recording business was in the mid-West Side. I was offered this gorgeous place in Tribeca, but when I took a cab ride to the studio with a stopwatch, it took too long. Now everything is downtown, but when I was there, nothing was downtown. But I’ve always lived in beautiful places. That’s kinda my karma.

Different definitions of beauty then?

Right. My place now isn’t much of an investment because it’s right on a cliff and someday it’ll fall into the sea.

Do you worry about how climate change might affect your place?

Well you know, I’m not allowed to worry about that because if I worried about that, I’d just be exhausted. I used to worry about it, but I said, ‘You know what? I’m going to live here.’ But when it’s gone, it’s gone.

How did you find it to begin with? Through friends you were visiting there?

My sister lived out here. My father was in Boston and I wanted to move to Italy. He said please don’t leave the country, and [my sister] Judith said, ‘Why don’t you come out to the west coast? We’re here.’ I found this ad in a local paper about a woman who had decided to leave her house behind for a year to go travel the world. She gave me the house, and that was that.

“All of a sudden I’m on NPR and all this stuff is happening. And my fans are seeing my album and they’re getting upset because there’s no piano.”

She just never came back?

[Laughs] She never came back. And I never left. I met my husband here, although we’re divorced now. Or ‘uncoupled’ as they say. Did you read that in The New York Times this morning?

No, what did they say?

There was a big story about Gwyneth Paltrow and her husband, and their ‘uncoupling’. So the woman who popularized the term ‘conscious uncoupling’ got a big story in the Sunday Styles section. I still read my New York Times. That’s the only paper I read here in this remote space. I’m still a New Yorker in spirit.

Do you have family in Italy? Is that why you were thinking of moving there?

Yeah, I’d always said I wanted to go to Italy to discover my roots, and I finally had a sudden sense of urgency and wrote an album there, after six months in Capri, Italy. I discovered my family there, and our relationship has just grown and blossomed. It’s just the most amazing family.

Did you not really know them until you visited?

Exactly. My mom wasn’t Italian, so she always discouraged me from going.

Why is that? Because your father made her not like Italians?

Well you know, she was from the Midwest, and I think she was really at odds with that culture. And of course, they didn’t like her, because she was German and English.

Got it. So what album did you write there?

Hotel Luna. It came out in 1991, when I was still on Private Music. (Ed. note: Ciani has her own label now, Seventh Wave.)

You’ve became more known for playing the piano over the past couple decades. Considering the renewed interest in your electronic music, where are you at right now in terms of what you want to write and perform?

It’s a dual identity, and the sides don’t speak to each other. So like with this concert in New York, I’m not promoting it at all to my fanbase. What happened was a few years ago, I was approached by Finders Keepers from Manchester, England, and that relationship was the start of this return to the past and to the future. They wanted to release my archival electronic music, and I wasn’t really prepared for the reaction it got. I thought it was an obscure label and that’d be fine—it’d be more of an obscure release. And then all of a sudden I’m on NPR and all this stuff is happening. And my fans are seeing my album and they’re getting upset because there’s no piano [laughs].

Were your fans confused? Did they think this was new material and you had just abandoned the piano?

I don’t really keep up any conversation with this. I’m hiding under a rock basically. I’m letting it take care of myself. One interesting detail here is this week is the 40th anniversary of when I went to New York in ’74. I went there to give a Buchla concert with a sculptor named Ron Mallory. I went just with my Buchla and I never went back to California. I hadn’t packed anything, but I called home and said, ‘Put everything in storage. I’m not coming back.’ Because I had fell in love with New York. So here I am—to me, this is a personal joke to myself, that I’m flying back to New York 40 years to the day of when I originally moved here. It’s kind of strange.

You’re coming full circle.

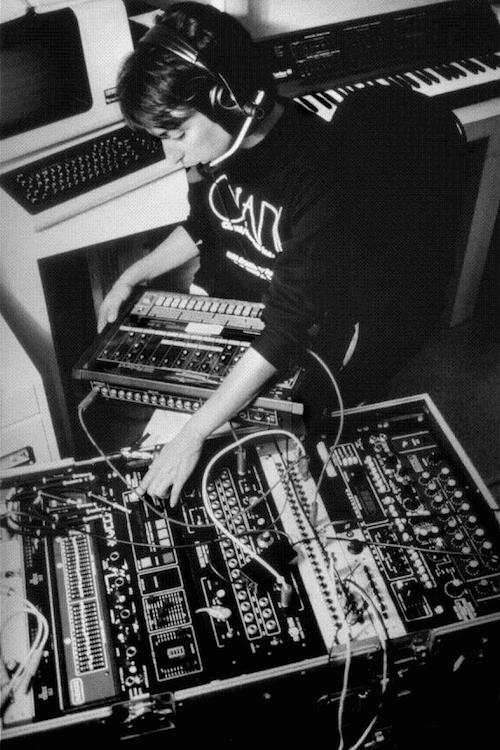

Right. And no one’s as surprised as I am. There were years where I made electronic music and didn’t touch the piano for 10 years. And then I went back to it partly for survival. Technology is a hairy thing. It’s either on or off; it works or it doesn’t. I used to have backup systems and all kinds of protocol to make sure an electronic concert [worked]. In those days, it was just so much gear—truckloads of stuff.

Did you have people moving stuff for you then?

Oh yeah. I should have married my carting company. They were there all the time. But what happened, is the Buchla was fragile, and it would break down. So I’d have to send it to California to get fixed. But then it’d get broken in transit when they sent it back. That’s how I’d have a nervous breakdown—because it was my instrument, and nobody in New York could fix it.

It was totally foreign to them right?

Totally. The head of the audio engineering society had no idea. And all of the other head honchos didn’t either. It wasn’t really their fault; Don [Buchla] wasn’t famous for documenting anything. To me, he was an eccentric; he was an artist… If the Buchla breaks now, at this stage in my life, I’m not going to get bent out of shape. In those days, though, it was my life.

Well there really was a symbiotic relationship between you and your instrument back then.

I thought it was alive. I had a relationship with it [laughs]. I once took this training in New York because I had an agent for Buchla concerts who wanted me to. So I did the training, and my issue was, I was in love with my machine. And at the end of the training, my realization was that people are just machines.

That whole relationship is kinda ironic; this machine that many people would view as less alive than, say, a guitar or a piano, became more alive than any other instrument around you because of how open-ended it was.

Well I was primarily a composer, and the life of a composer is very restricted in a traditional sense because you’re reliant on other people performing your music. In those days, I saw the politics of new classical music and it was very discouraging. Being female, they said, ‘Oh, you have no right to conduct.’ And this and that. So when this concept of a self-controlled musical environment struck me, it was a godsend. It was like, ‘I can control it; it’s mine. And no one can tell me what to do.’ A natural euphoria happened.

What did these massive machines sound like when you first heard them? While it’s easy to access the sounds of most synthesizers now, it must have sounded very alien back then.

The most important thing about it was not the sound. It was the way the sound could move. I found the frequency range of traditional instruments to be really subdued, with no low or high end. With electronics, you went the whole gambit. Other music sounded kind of muffled. As a composer for traditional instruments, you’re limited by things like how long someone can hold their breath or the fingerings or the ranges. With the Buchla, suddenly all these doors opened. You could trans-morph a sound, like you could turn a bass to a wind, fly it around the room and turn it upside down. The other fascination in academic music at the time was the idea of complexity. You had to be complex or you wouldn’t be worth your salt as a composer. But with the machine, complexity was easy. That whole concept went out the window, so I could return to simplicity. Because I was in love with this machine, I was very patient. People would ask me what it was, and nobody understood it. So I wanted to develop a technique for it the same way people have a technique for playing the violin. You know, Don Buchla viewed it as a performance instrument, and I believed him. So I wanted to perform it. And that was really challenging. I try to base my playing now on what I did in the ’70s but I’m finding that new machines are more limited in terms of what I used to be able to do.

How so?

Well the filters have been redesigned so they don’t sound the same. They don’t have the same response in terms of what I try to do. It’s little things, like being able to expand and shrink an envelope. And the heart of the system—the arbitrary function generator—goes in a circle now instead of left to right. I used to be able to flip switches on the fly during a performance and that’s a lot harder now. It’s an open architecture so you bring your own approach. And the things I developed as techniques weren’t set in stone. Don never knew about them; he never used them. Don and I play a lot of tennis now, so I’ll tell him how I’m having trouble with the stability of the machine when I do this or that. And he’s like, ‘Well, just don’t do that. Change your music. Just make noise.’ So I’m like, ‘Okay, I’ll just make noise like all the other guys.’

That’s an important distinction to make. You approached the Buchla as a performance instrument, but many people back then looked at it almost as if the machine was controlling you. Like if someone saw you performing a Buchla, all they would see is someone twiddling some knobs, with little technique involved. But you really thought the process through; it wasn’t just happenstance or ‘making noise’.

Yeah, and it’s documented, oddly enough, by this National Endowment paper I wrote. In those days, I thought this was going to be the next instrument, that every home would have one and music would be flying through everyone’s three-dimensional space in their home. Of course, the other given about technology is that it never stays the same. A violin is a violin, even if it’s a hundred years old. But these instruments have a dependance on parts and as the parts change, so does the instrument itself. The concept of performing with this instrument can endure. The whole idea with the Buchla was it being portable so you wouldn’t be stuck in your home studio. You could go out and do sessions or bring it to a concert hall. It’s really a matter of time; the more time you spend with the instrument, the deeper you go.

So do you find yourself wanting to spend more time with the instrument now?

That’s a tricky question. In my early life, I was happy giving myself 100-percent to this thing. But now, I like to play tennis, and I like to visit my friends. I can’t give my life to the machine anymore. So I had a deep resistance to getting back into it. I didn’t want it to swallow me up. And so it sat here for a long time. It took this [Finders Keepers] situation to change that. Andy and Sean, my two Manchester buddies, make things so much fun. We’re going to do a tour of Eastern Europe in the fall. I’m going to bring my Buchla; hopefully it makes all the flights and all that. We did a concert last year in L.A. and I didn’t even bring my own Buchla. I borrowed one from Allesandro [Cortini]. Do you know him?

He’s from Nine Inch Nails, right?

Yeah. He gave me this little easel I’d never played before. But we did a wonderful concert that was so much fun. It was tough pulling off solo Buchla concerts. I did it but it was very mentally intensive.

Tough in terms of what you wanted to pull off or tough because the audience didn’t quite get it early on?

Oh, the audience was totally receptive. In fact, we’re going to release some of these early concerts, like one I taped in 1975 at the WBAI Free Music Store. I did two 45-minute sets there. Then I did another one at Phil Niblock’s loft. But anyway, I’m just amazed when I hear that 1975 concert. Carrying that off—keeping it going and making all of the transitions—was very intense, like an out of body experience.

Since you have a really good melodic sensibility, was it always important for you to pull off something that had an emotional resonance with people rather than something that becomes more about the process itself?

For me, it’s always been about the emotion. When I listen to that old concert, I feel it. The vocabulary was so different in those days. Even though the audience was very appreciative, nobody else got it. I think that’s what led to me synthesizing my electronics with my romantic classical root system. I naturally went towards something very simple, although the technology retained its edge for me. I loved the challenge and the evolution of those instruments. I loved getting up every day and seeing that everything was different. It’s stimulating creatively—not boring.

How did you transition from performing experimental music to making commercial material for major ad clients?

My first experience was when I was still on the west coast. I would go to the tape music center at Mills College. You could rent studio time there; you weren’t supposed to do commercial work, but my boyfriend at the time was from Milwaukee. And his neighbor was a filmmaker doing commercials for Macy’s. They had a Christmas package that needed music, so I did 10 spots for Macy’s. I did it all electronically, and they were a big success. I got like $1500 and it was like, ‘Wow, this is great.’ Once I finished graduate school, I looked around and nobody wanted me to be an engineer. I needed work so I started knocking on doors. One of my clients required me going to L.A. to record, so I moved because there was more commercial work there and the film people could show me how to score pictures. Then this day came where I came to New York in 1974. I loved it, but within moments, I was starving. It was like, ‘Show me the money.’ I never thought you should start at the bottom; I always thought you should start at the top, so I started cold-calling the top 20 agencies. It was exhausting, but if you keep banging on that door, eventually something cracks open, and once you get your foot in, things can multiply. The big break for me was the Coca Cola thing.

Were you already working for [the major ad agency] McCann Erickson at that point?

No, I had tried getting a hold of them for a year. This guy had stood me up twice. We had a meeting this one day, and I said, ‘What do you mean he’s not here? Where is he?’ ‘Well, he’s in the studio.’ ‘Where is his studio?’ They thought I was so huffy. But I marched over to the studio, I opened the control room door and I saw the head of music from McCann Erickson. I said, ‘You have an appointment with me.’

How did he react to that?

The guy looks at me like I’m from another planet. ‘Oh really?’ Well this is the weird thing—they were doing a Coca Cola session and there was a hole in the song. I tell him what I do, and he says, ‘Well can you do anything in this space? And I said, ‘Yes.’ When you’re really desperate, you make things happen. And I was very desperate then.

So you came up with that sound on the fly in the middle of their session?

Well he said, ‘What do you need?’ ‘I need to get my Buchla.’ ‘Well how long will that take?’ I called my cartage company and it took them an hour to get there. So my brain is racing because they don’t know this electronic stuff at all. I thought, why don’t I make something generic so if they want to use it in different spaces, they can? Bubbles, you know? There’s a lot of magical moments where these things happen and this was one of them. After that, people were wondering what you could do with this Buchla. I mean, it had no keyboard. And this [head of music] guy was a producer from Motown…

Billy Davis right?

Yeah! Billy said, ‘Why don’t you play a keyboard instrument? Then we could use you more.’ And I said, ‘Well I don’t play keyboards.’ Of course I did… So he said, ‘Well, I’ll buy you a string ensemble and every time we use it, I’ll take 80 bucks off the session. And you can pay me back.’ So they started putting me on every string section. And I also got to do fun stuff like the sound of heat, the sound of all the poetic stuff I like to do. That was fun for me—being with all the session players.

Did you form your own company around that time?

No, I was still a session player then. That’s a really important part of the process, because I got to be on the inside. I got to work with all the production companies because they all wanted this electronic thing. My frustration was they didn’t know how to use it.

How many years later did you form the Ciani-Musica company?

Not long after that.

Is there any campaign you’re particularly proud of from that time?

Well there were two areas I loved—the microcosm stuff, short sounds that are under a second for AT&T or the logos. They were a whole world; with electronics, you could go in there surgically and really control everything. Then the other thing was this big campaign for Lincoln Mercury. You know, I had a lot of creative freedom. That time was the height of creative impetus, before the suits took over. At a certain point, all the Harvard b-school guys came in and destroyed creativity. I was working for music directors who really had carte blanche and they gave it to me, like, ‘Just do it.’ I did the Columbia logo, I did a wonderful spot for Eveready, a great spot for this monster lawnmower, a lot of stuff for General Electric. The GE Beep, the talking dishwasher, was a major breakthrough. Because when they did that, it was the first time a dishwasher made a sound. And they loved it. It won all kinds of awards and then we had to do Son of Beep, and Cousin of Beep.

Did you ever stop and think, ‘Wow, this is really surreal, being paid to make sound effects?’ When you first got into this, you must have thought you were going to make your money through performing.

Well the reason I did all that was that my number one passion was my recordings. The reason I made all that money was so that I could make my records. And once I got my records going, I pulled out of commercials. There are people I knew then that are still doing it; I’m just amazed.

And are they happy?

I guess so? They must be making a lot of money.

You never thought about going back to it?

No, I never thought about going back to it. For a while, I thought about film scoring but I never got that off the ground. I did that one film for Lily Tomlin (The Incredible Shrinking Woman) but you have to go at Hollywood very aggressively. And I’m just not that aggressive anymore.

Did you do most of your commercial work in L.A.?

In L.A., I was exchanging synth lessons for scoring lessons. I did The Search T.V. show. I had fun with people who were intrigued by this new thing. And once I moved to New York, the commercial thing happened and I founded my company Ciani-Musica. I built a studio because I wanted to leave the company to my fellow workers once I moved onto the concert/record world. But they didn’t want it. I didn’t realize that nobody wanted to run the show.

So did you end up selling the studio?

No, I just left it. I don’t know who got it. We sold a lot of the equipment at an auction… But I was sick at the time. I had the early stages of breast cancer, and I had to get out. I just wasn’t in any shape to handle a graceful departure.

Did you feel like you couldn’t have a full recovery in New York because it was so stressful there?

Totally. I thought I was in the fast lane and my body was telling me I had to get out. So I did.

Were you thinking of moving already or did you feel forced to physically?

I wasn’t really sure. I was touring in Spain that winter, and I remember having a good thing going. If I was thinking of moving anymore, it’d be Italy, but I didn’t have a place lined up. And then I couldn’t go to Italy because my dad was sick. So the stepping stones were kinda laid out. You walk on them, and they take you someplace else.

Sounds like it all worked out in the end though.

Well it’s not the end yet [laughs].

No of course not. I just mean how you ended up staying there.

Right. And I have no complaints. It’s like paradise here, and I can drive to [San Francisco]. It’s about an hour away. I love it—I love playing tennis, and I love hiking—but I miss people.

I thought you said you have more friends now.

Well I have to visit them; they don’t visit me. I think of this as my studio. I don’t know; I haven’t figured it all out yet.

Since you gave up playing the Buchla for a long time, did a lot of your friends have no idea about this earlier life of yours?

Well it’s like this archeological layer that’s been rediscovered. And it’s confusing for me to even talk about it with people. That layer, when it occurred, was so misunderstood in many ways. When I go back and listen to the early stuff, I have a new appreciation for it. For the longest time, I thought it was so esoteric. How do you get people to listen to something that doesn’t have a beat, you know? It doesn’t sound like anything, you know? But now, with this concert, Andy said, ‘What we’re doing is not what people do. It’s not beat-oriented; it’s not pre-fab. We’re live on the stage, creating it in the moment.’ I like that concept. My old electronic concerts were by the seat of your pants, and the later ones were more plotted and planned. So now I’m going back to it with a new spirit, which is fun. And I love the fact that this is called the Unsound Festival. I can do ‘unsound’ the way some people do ‘uncoupling’.

So are you heading into this as more of an improv situation?

When we did our L.A. concert, it was trial by fire. It’s just a wonderful fit. I trust that what we do is going to have a wonderful energy. Do we know what we’re doing? No. When I did the L.A. concert, I was using snippets from my 1975 Buchla, and to me, they’re like my little children. They’re like little flowers, little plants. I can hear one note and I already know what it is. So it’s very organic for me that these things are so connected. This time I’m using snippets from 1975 and I’ve recreated some of them in the Buchla.

Did you do any rehearsals?

No.

Very trial by fire again then.

Right, but that’s what makes it so alive.