We’ve gotta be honest here: while self-titled has always wanted to jazz’s more experimental records, we’ve yet to take a deep dive into the genre’s many sprawling discographies. Enter Rafiq Bhatia to save us from ourselves, then; the composer/guitarist/Son Lux member was kind enough to break down five of his favorite albums on the avant-garde side of the jazz spectrum. Check out his lengthy record buyers’ guide below, along with a streaming version of Bhatia’s own solo album Breaking English, which hits shops though ANTI- Records today…

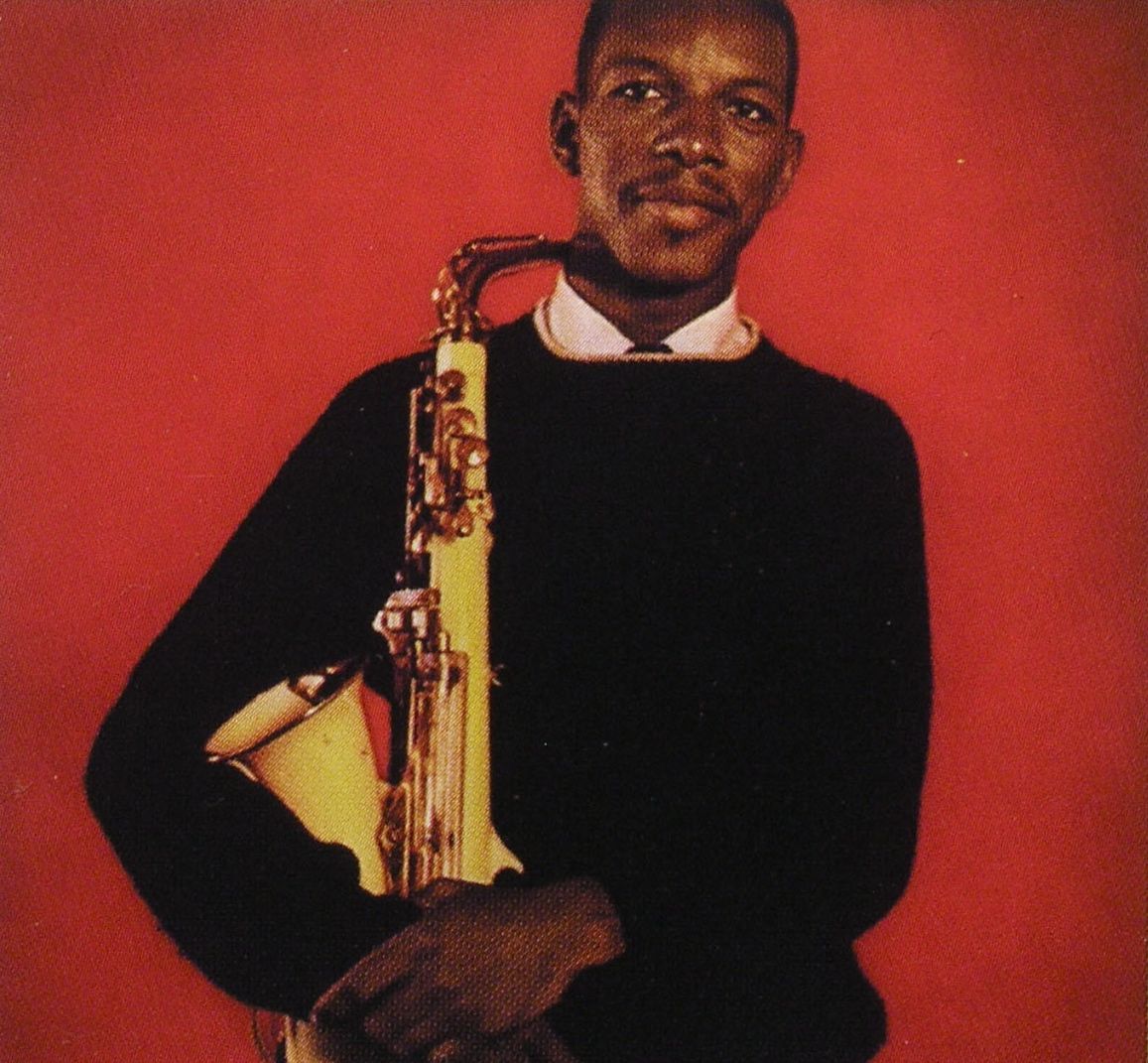

John Coltrane

Stellar Regions

(Impulse!, 1995)

This posthumously-released LP reminds me of the majesty of life, as well as how fleeting it is. Coltrane’s sound on this record is especially joyous in that agitated sort of way; so ecstatic it registers as borderline crazed. There’s a volatility to it as it frays around the edges, warping from noise into singing, pulsating notes in swinging, pendulum-like gestures.

This band has so much flow. Rashied Ali’s drumming crests and bubbles over Coltrane’s buoyant phrases. I relish the long periods in which the ensemble is distilled down to a duet between the two of them, a darting stream of consciousness in which you can perceive every micro-interaction. That pared-down instrumentation makes the full-ensemble moments all the more consequential. Alice Coltrane chooses her moments to surge, sending out waves of piano that glimmer like a sun-lit waterfall. As always, Jimmy Garrison seems to uproot his sound straight out of the ground.

I grew up around esoteric religious ideas and narratives, and this music reminds me of them constantly. “Offering,” in particular, feels like a prophetic journey encapsulated in sound; it’s in turns regal and terrifying. Crippling insecurity gives way to unshakable confidence on a dime, and the whole band somehow seems to understand when that’s supposed to happen. This track also features some of the most muscular saxophone playing I’ve ever heard. Coltrane transcends both his instrument and many traditional parameters of music-making altogether in favor of a more unbounded expression that feels both superhuman and deeply human at once.

Stellar Regions manages to exhibit extraordinary range while feeling unusually unified; like many of my favorite recordings, it feels like it’s from its own planet. The title track reminds me of sheets of torrential rain lit by an undeterred sun. “Iris” is a stress dream, a series of windowless rooms that lead into each other, a never-ending puzzle. “Configuration” starts out like a train careening off the tracks, ending up inside a particle accelerator. I wish I could bottle up the trio feel from the last 30 seconds and make it last for 45 minutes.

If you’re able to, I’d suggest listening to this album in mono as the extreme panning is pretty distracting. The alternate takes are wonderful, but I recommend checking them out separately…. You’ll need a break after the face-melting “Tranesonic,” a rare recording of Coltrane on alto saxophone.

Alice Coltrane

Journey In Satchidananda

(Impulse!, 1971)

Sonically speaking, this may be the record that resonates with me the most on this list. Harp, bells, and tanpura cascade together in webs of tangled silk, glistening so luminously that you forget how architectural they are, how fundamental they are to the rhythmic undertow. There’s a dry breathiness in Pharoah [Sanders]’ sound that translates almost like tube amp breakup as he focuses it into a beacon. He’s comfortable riding the wave at times, fluttering sideways in and out of the ensemble’s path. But elsewhere, he exudes a gravitational pull that is strong enough to compel the music into his orbit, situating himself right in the center of the sound.

Coltrane’s harp, meanwhile, feels like it’s coming from everywhere but the middle, sometimes all at once. Like Ishmael Butler of Shabazz Palaces, her wisened sound seems to emanate from somewhere within the depths of my subconscious. Even when her playing is precisely syncopated, undergirding the tripletized motion of the rhythm section, it still manages to feel atmospheric and diffuse, camouflaged amidst the sparkling tangle of tempura and bells.

Cecil McBee is both wildly imaginative and consummately supportive behind the bass, oscillating so gently between the two roles that even his most surprising decisions feel wholly integrated into the ensemble. Rashied Ali’s pensive, relatively restrained playing helps make that possible.

Though the final track, “Isis and Osiris,” is a live recording featuring a slightly different configuration of musicians (Charlie Haden replaces McBee at the bass while Vishnu Wood joins on Oud), its tremulous, pulsating feel is right at home on this album. When Ali does shift the group into a more gridded feel two thirds of the way through, it feels futuristic in its push and pull, almost like something that might have ended up on [Flying Lotus’] Cosmogramma [album] half a century later. But though the music is heavy in its impact, it’s also light on its feet, retaining a featherweight quality until the last breath.

Ornette Coleman

Science Fiction

(Columbia, 1972)

Over the years, the genre of science fiction has presented a contrasting lens through which we might better appreciate the particulars of our own reality. Ornette Coleman’s strain of it is no exception: time waxes and wanes while melodies ooze out gesturally in a way that somehow seems more grounded in the physical world than gridded music ever could.

Hearing “Civilization Day” again today, I was reminded of how I felt when I listened to Smino’s blkswn for the first time recently, or when I first experienced ATLiens. (Maybe I’m just sleep-deprived right now, but this analogy of Ornette : 3stacks : : Don Cherry : Big Boi is making way more sense to me than it probably should?) Their approach is so fully-formed and personal and bold—it seems like it came out of nowhere. Charlie Haden’s bass is a rugged engine, powering and grounding Billy Higgins’ more feathery touch.

My favorite cuts on this record feature the voice of Asha Puthli: “What Reason Could I Give,” and its counterpart “All My Life.” They feel like pop music from the future past. The shimmering, cloud-like sonorities are the result of both wide intonation and a distinctly melodic approach to harmony. Deconstructing precisely how the ensemble is all held together is almost impossible, or at least besides the point—the music is in time and rubato all at once. It smears like a distant dream; aural Dalí.

Puthli is a pioneer: she got her start singing jazz in Mumbai nightclubs before moving to New York on a dance scholarship from Martha Graham. After making her mark in the jazz community with this record, she switched her focus to music that masqueraded as disco but drew from a breadth of influences. Those records have been sampled for tracks from Biggie, The Pharcyde, and Jeremiah Jae, among others. I was struck by this quote in which Puthli describes the resistance she encountered when trying to get a foothold in the United States (via The New York Times):

Melody seems to permeate every aspect of this record: the harmonies tug at my heartstrings, the rhythms all sing (it might be tough to think of a better example of this than Dewey Redman’s phrasing on “Law Years”). Sometimes Ornette’s sustained sharp intonation reminds me of MIA’s singing. Whatever Redman is doing four and a half minutes through “Jungle is a Skyscraper” punctures a few holes in space-time.

These days, this record is most readily available as The Complete Science Fiction Sessions, which includes a number of bonus tracks. I prefer to listen to the record in its original, condensed format, which ends with “Jungle is a Skyscraper.”

Vijay Iyer

Reimagining

(Savoy Jazz, 2005)

Vijay Iyer has had a profound impact on my life for more than a decade; he’s been a teacher, mentor, collaborator, and friend to me. But long before I met him, I heard Reimagining, and it floored me. I had stumbled upon something that translated multi-dimensionality into momentum: it was kaleidoscopic, revolving, revolutionary.

Iyer is a master of rhythmic orchestration: every instrument functions on its own time scale. No matter how dense the fray becomes, they all have space to breathe, nothing is riding on anything else. Nobody seems to contribute more to this end than Stephan Crump, whose bass playing forms the core of this record, and Marcus Gilmore, who as a teenager was already adept at improvising by subtraction rather than addition. His silences frame some of the hardest-hitting moments on this album, gems which could have easily been smoothed over by less discerning drumming.

There was something about Iyer’s playing on “Revolutions” that drew me in immediately the first time I heard it; the kind of flowing pianism that characterizes Ravel’s sonatine hardened into a serpentine form that accumulates momentum behind its mridangam-like rhythmic cadences, cracking like a whip into the downbeat. Perhaps Rudresh Mahanthappa’s robust, metallic tone on alto saxophone also subconsciously reminded me of the reedy Ginans my grandfather used to sing me to put me to sleep when I was a kid. Those Ginans and mid-’90s gangster rap were my first two musical loves—I never thought there would be a music that could so readily reconcile them until I heard “Song for Midwood.”

In searching for an interview with Iyer from this era, I stumbled upon reviews describing this music as “academic,” “mathematical,” or just plain “forbidding”—views that I have heard echoed by others throughout the years. I could never really understand how anybody could come away with that reaction after spending time with this music; to my ear, it has always felt full of life and welling with emotion. Is it not plain to see how much love, pain, care and attention to detail went into making it? How not a single decision feels like it was taken for granted?

Honestly, it’s hard not to take this kind of reaction a little bit personally—before Reimagining, I’d never seen a South Asian musician making improvisation-driven music that was truly hybrid like this before, free from the pull of Western appetites hungry for stereotypes of Indian culture. It felt like—and still feels like—music made for someone like me. People tend to think of art and aesthetics as entirely a matter of taste, as though preferences are cultivated inside of a vacuum without any influence from factors like relatability, privilege, and reductivism. If your viewpoint is so clouded by stereotypes that you can’t recognize somebody’s personhood, it’s going to be tough to understand or appreciate their music.

Crafted in the aftermath of George W. Bush’s reelection, this album reexamines the sentiment of hopeful white liberalism of John Lennon’s “Imagine,” begging the question of what happened to those ideals. I dare you to listen to this whole record all the way through, think about the horrors of the past few years of American history, and tell me you don’t feel something.

Okkyung Lee

Ghil

(Ideologic Organ, 2013)

The singular cellist and improviser Okkyung Lee’s pulverizing virtuosity is not for the faint of heart. Much of Ghil’s 45 minutes s is the sound of a breaking point; you can practically (in some cases, literally) hear the hair stripping off of her bow, her strings buckling under the pressure. There’s an astounding degree of control inside of all of this physicality, a form of musical organization based around the development of sound itself. The opening minute of “The Crow Flew After Yi Sang,” for instance, reveals Lee’s penchant for finding the most periodic elements hiding within tangles of Jackson Pollack-esque bursts of colorful sound and dragging them out into plain sight (for a different take on a similar idea, see Dawn of Midi’s Dysnomia). I’m awestruck by the speed of thought and clarity of intention that it must take to make music like this. But more importantly, hearing Lee push sound to its limits is both grounding and transcendent—something like the Sufi concept of “annihilation in the eternal.”

The concise pieces that make up Ghil put process on full display. Large sections of “Two To Your Right, Five To Your Left,” “Strictly Vertical,” and Two Perfectly Shaped Stones”—which for a moment comes eerily close to the sound of Colin Stetson’s bass saxophone—bring to mind the image of someone working with a giant loom, with Lee’s forceful bow work representing the friction against the fibers being threaded through.

Ghil was produced by Lee’s friend Lasse Marhaug, who used a portable tape recorded from 1976 to capture Lee improvising in a number of evocative locations around Norway. It’s a bold move; the results are often so dry that the music appears to originate directly in between your ears (in these moments, the “threading of the loom” starts to feel more like brain surgery without the anesthesia). But the closeness exaggerates the tiny human and mechanical aspects of Lee’s performance while the tape responds dynamically, saturating as she digs in.

Perhaps my favorite stretch of this record arrives six minutes into “The Space Beneath My Grey Heart,” when an accumulation of tearing bow strokes gradually yield to a throttling shuffle of low low gestures, like something between Tom Waits’ more industrial blues and a smashed field recording of windshield wipers. Landing on such a stable harmonic progression feels like stumbling into a clearing after the intense focus of the timbral improvisation that has preceded it.

Though I can largely identify the cello throughout this record, there are moments where its interaction with the tape suggest dramatically different sound sources. “Meolly Ganeun,” an onslaught of skittering, Buchla-reminiscent squeeks gives way to guttural shards, punctured periodically by almost ring-modulated sounding higher pitches. Eventually, the whole thing coalesces into a throbbing wall of harmonic frequencies. In this final chapter, which also includes the alternately regal and sputtering “Over The Oak, Under The Em,” the tape is pushed to its limits in a way that mirrors the muscularity we’ve heard from Lee throughout the album. These moments represent the singularity between Lee’s playing and Marhaug’s committedly colored production—it becomes hard to tell exactly where the struggle is coming from, but it goes straight through you nonetheless.