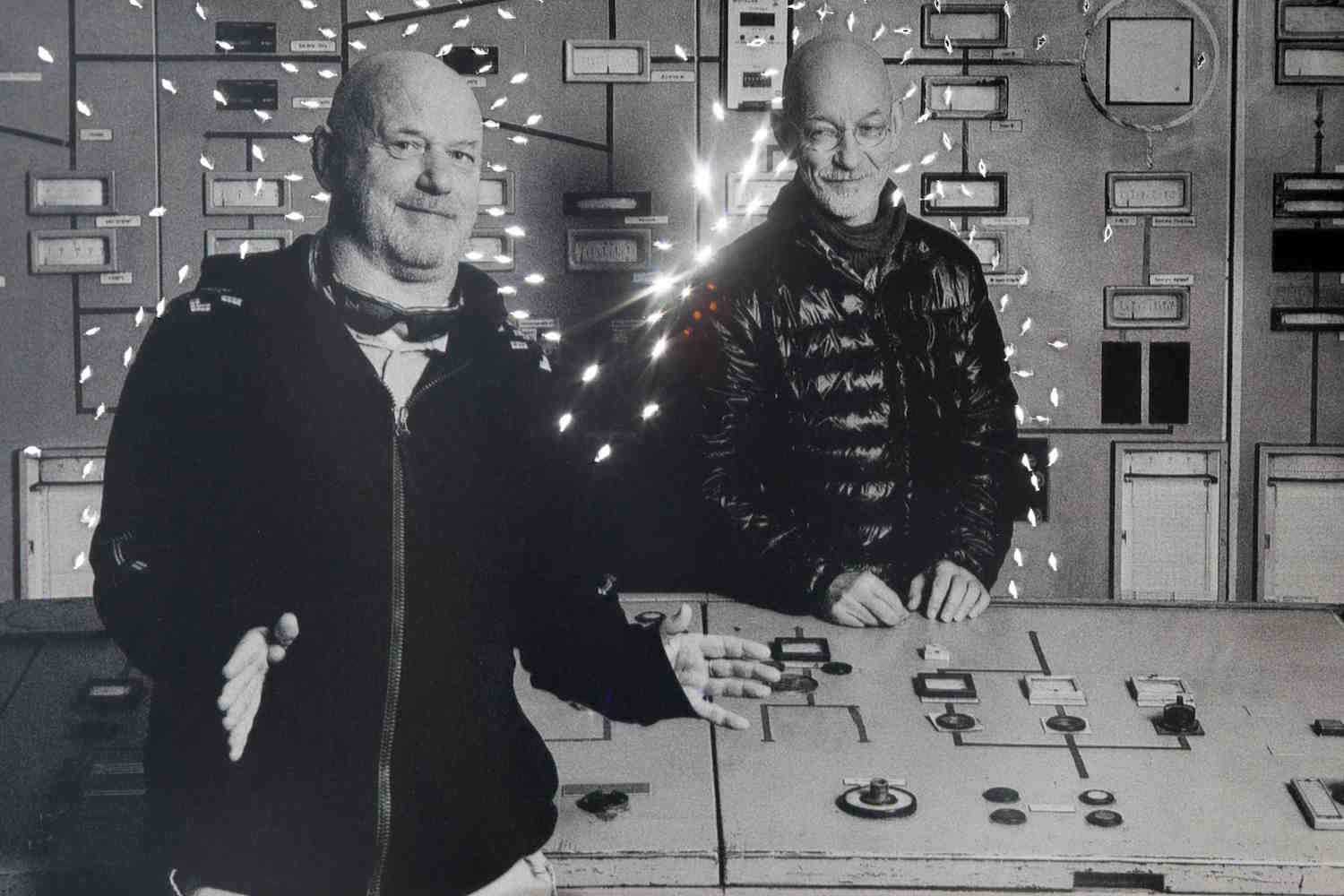

In honor of the excellent ambient record The Orb released on Kompakt today (COW / Chill Out, World!), we asked Dr. Alex Paterson and his longtime collaborator Thomas Fehlmann to cut an exclusive chill-out mix for our Needle Exchange series. Presented in two parts below and recorded in their respective London and Berlin studios, it’s a welcome return to the White Room vibes that set the stage for ambient-house in the late ’80s.

Have a listen down below, then check out separate interviews that explore both of the boys’ musical backgrounds and address important issues like the time Paterson pissed off Paul Oakenfold by going on a joy ride with his old buddy James Cauty of The KLF…

Halim El-Dabh – Wire Recorder Piece

This Mortal Coil – Thais

Ryuichi Sakamoto – Dawn

apollo 14 lunar orbit

Ennio Morricone – Voce Seconda (Haruomi Hosono Remix)

Lee “Scratch” Perry – Black Shadow

Bob Marley & Artie Glen – Selassie is the Chapel

Marsen Jules – Coeur Saignant

apollo 14 tv trans

Pink Floyd – The Narrow Way Pt1

Art of Noise – Crusoe

water dripping

The Orb – Alpine Evening (Prince Thomas Yoga Mix)

The Future – Ambient States

The Orb – 4am Exhale

This Mortal Coil – Morning Glory

Clytus Gottwold – Lux Aeterna

Brian Eno – An Ending

The KLF – Alone Again With the Dawn Coming Up

TRACKLISTING (THOMAS FEHLMANN):

Peter Michael Hamel – Colours of Time (Deepchord’s Carolina Forest Mix)

Sun Electric – Bellows *

Daniel Lanois – Time On

Prins Thomas – H (Orbient Mix)

DJ Koze – Bodenweich

The Orb – 5th Dimensions

Jeff Mills – Phoenix

The Orb x Jean-Michel Jarre – A Frenzy Moonlight With Bob & Clara *

Ryuichi Sakamoto + Alva Noto – The Revenant Main Theme

Serengeti – Maestrale (President Bongo)

* previously unreleased

self-titled: How are you doing Alex?

Alex Paterson:Pretty good. I’m just going to get a better signal out in the garden.

You’re at home then?

Yeah, just doing some interviews.

Have they been better than usual?

Not too bad at all. You have to take them at face value these days. I’m ready for anything.

Cool. Let’s start by talking about your earliest memory of being exposed to something you’d consider ambient music.

I suppose it’d be the classical music my brother played. And then sort of folky stuff, like Bob Dylan and—dare I say it—some of the early Led Zeppelin stuff.

Led Zeppelin?

Yeah, the third album. It’s highly underrated, that album. And then there was King Crimson, with Robert Fripp’s pioneering guitar sound. I was very fascinated with the panning devices they used on Led Zeppelin II, too. I remember standing in front of a stereo at an early age and listening to the sounds going back and forth on the speakers. That was mad. I enjoyed that immensely.

Ambient didn’t really come out until the first two albums Bowie did in Berlin with Brian Eno—Low and Heroes. Off I went after that.

Those Bowie and Eno records must have sounded so strange when they first came out.

Yeah. When Youth and I were growing up as teenagers, we had this turntable that’d just repeat the records—the needle would come off and play it again, all night. That helped us discover that side two of Heroes was the best album ever.

Is Youth one of your oldest friends then?

He’s definitely my oldest continual friend. He was 12, and I was 13, when we met at school.

Where you guys the outsiders at school?

That’s a weird one, really. We didn’t really like being there. It was a boarding school—a school where you weren’t allowed to go home. If you tried to run away, they’d pick you up and take you back there. It was one of those schools—not very nice. We looked after each other. The people from up north didn’t really like people from London, so they’d bully you if you were a little bit weak in any way. Boys can be nasty when they’re growing up. So, yeah, I’d look after him, and one of the things we’d do is play music like Alice Cooper, David Bowie, and T. Rex. Every time I go under at the dentist, I think of that Alice Cooper tune. Maybe that’s just me. [Laughs] It’s the one that starts with a dentist drill on Billion Dollar Babies.

How did you end up in boarding school? Were you a bit of a prankster as a kid?

Well my mum didn’t find me very amusing by the age of 10 so she was just glad to get me out of the house. She was a young mom, and I’d lost me dad when I was 3, so I can’t really blame her for that. My older brother [Martin] saw me through all that, though, and he got me into music at a very early age. He played guitar, and was in bands when we were growing up, so he’d take me to see shows.

What kind of bands?

Prog-rock and kinda folky, weird shit. I appreciated the escape from the totalitarian state I was being incarcerated in at school—the one that wanted me to become a blue collar worker for the state, basically. They were trying to indoctrinate me, or worse—make me a [priest] or something. [Laughs] Help!

When I say music saved my life, I mean it, you know? It’s not to be taken lightly.

It sounds like your brother did a lot for you, and helped you become a very open-minded listener.

For sure. I’ve always thought of him as the reason I got into music in the first place. He died 15 years ago. It was sad he went so young, but these are the cards you’re dealt. You just have to get stronger with them. There are ways to mature with them without being stupid.

You remained close throughout the years then?

Yeah, he was always making music, and doing drum ‘n’ bass back in the ’90s. Then he passed away in 2001. I remember him playing the harmonica in the yard once, and this dog was howling in tune with the harmonica so we recorded it. That’s on “Tower Twenty Three” from Bicycles & Tricycles to kind of say goodbye to my big brother.

When did music become something you yourself wanted to make?

When the technology caught up with my brain. I started off pretty young in bands, as everyone does. But I never got very far. The most noticeable thing was with this band called Bloodsport, then Killing Joke nicked the name for one of the tracks on their first album.

I was a bit of a singer, and used to do a lot of singing with Killing Joke when they didn’t have enough material to do a set of their own [songs]. I got noticed by Paul Cook of the Sex Pistols and they asked me and Youth if we’d join the to reform the Pistols, but we politely said no. That was after the other things that’d happened—all the Ronnie Biggs things in Brazil. We didn’t want to be following that, so anyway, they went off and did The Professionals.

And to bring things full circle, Paul Cook played drums with The Orb at our 25th anniversary gig in London. He had fond memories of me singing on stage still, so that was quite sweet. I did a John Peel session once, where I did a version of the song “No Fun.” Which, when we did a gig with Iggy Pop, he actually came over and said, ‘That’s a really cool mix, man, a really cool version.’ I was bowled over by the fact that he even knew I existed, let alone talked to me about a track of his I’d covered in the ’90s. That was cool—brilliant, you know? In my old days of being a roadie for Killing Joke, his roadie was one of my best mates. There’s big circles of everything in England. We don’t know everyone but if it’s a power of three, we probably know that person.

Did your roadie days make you want to be in a band yourself, or did it not really appeal to you?

I don’t know. That’s a good question, because I spent a long time being a roadie. What I discovered with [bassist] Paul [Raven] is that it’s a big experiment of sound, which I was logging, ready to unleash the Orb, I suppose.

It all fell into place because I’d always been a really big fan of 98.7 Kiss FM back in the old days. By the mid-’80s, the music had suddenly changed. It opened up house music to me. And I was really into the Rephlex and Metroplex stuff. Youth and I were living in this little coach house in South London in 1987, and we said, ‘What are three things we want to have done by 1988? Start a record label, form a band, and start a pirate radio station.’ Now I do my own radio station called WNBC.LONDON and I’ve got me own band, and I’ve had several record labels. That’s the worst one of the lot; having a record label, because people think you have loads of money but you don’t unless you’re really, really successful.

Uh oh, my line’s buzzing. Can you just ask one more question?

Sure, tell me one memory from your days of doing a chill-out residency for Paul Oakenfold.

It was a weird one. It was a room where you needed a VIP pass to get in. And I was told by Paul to not play any dance music, which I thought was kind of apt because I was playing ambient music anyway. The biggest moment for me wasn’t in The White Room itself; it was afterwards, when we all went off to Jimmy [Cauty’s] American police car. The club was right next to Trafalgar Square, so off we went in the American police car, and Jimmmy decided to show off and put all of his disco lights on it. All of these cars followed us. It was straight out of a film; we had kids hanging out of their windows…. It was a monstrous moment. And then the next week, Paul told us if we ever did that again, we’d not be doing another ambient room [laughs].

Let’s start by talking about the role of ambient music in the world, especially given how chaotic it’s been lately. What’s the earliest memory you have of listening to ambient music?

Thomas Fehlmann: The function of chill-out might have existed before, but to be honest with you, the first time I got into what we call ambient was via Brian Eno’s Discreet Music on Obscure. I’m not quite sure whether the Fripp & Eno record was before that; I guess it was. When I first heard No Pussyfooting, I didn’t feel relaxed at all. I felt this electronic sound getting in my teeth for some reason. That physical reaction interested me a lot. I was curious and bought that record straight away.

I was never really into New Age music. For me, ambient was music to chill-out to, but it was also food for thought. I liked that arty angle. It had quite a big spectrum on the Obscure label, from John Cage to Gavin Bryars to Brian Eno himself. That left a big mark on me. Some of it was a little unconscious. It was interesting to see a musician as commercially successful as Brian Eno dabble in this arty area. The Obscure series was a little hard to get. I had to call the label that was distributing it in Germany, Polydor, and say, ‘Where are the records? What is going on with this? Are you serious? Don’t let us down!’

What was it about that series in particular that appealed to you so much?

I was attracted to the artiness of it. I was an art student at the time in Hamburg, so this parallel scene of what was going on with music at the time was something I had to really hunt for. Luckily, early on, I had a chance to see Philip Glass live early on with Einstein on the Beach. That was where I started to get into serial music and stuff like La Monte Young and Terry Reilly. Admittedly, I didn’t follow those two artists when they were releasing their most well-known works. I came to them later on through the information that gathered around the Obscure releases.

Why did you decide to leave Switzerland and move to Hamburg? Did it just seem like there was so much more happening with the art scene there?

There wasn’t an art academy at that time in Switzerland. I was already in an experimental arts school in Zurich, which was basically a private school. Being there for two years I decided to take a gamble and apply for a space at the academy in Hamburg. As you might have guessed, it worked.

How soon after moving to Hamburg did you found Palais Schaumburg and start getting into music beyond art?

Two incidents made me switch from visual arts to music. One was a visit by Robert Fripp in Hamburg when he was touring his Frippertronics. He did a tour where he played record shops for free in the afternoon. I saw him there, and was very excited to hear the concept of him coming from this big stage with King Crimson. It was this contradiction of coming back to his roots of the record buying public.

After his gig, I explained how I was an arts student in Hamburg and asked if he’d be interested in playing a concert there. He said he’d be staying in Hamburg for a week and wouldn’t have too much to do, so I’d hang out with him for tea in the afternoon, chatting away, starstruck at first, and couldn’t think of too much to say. He was very relaxed and acting normal in a way that opened me up. Two days later, he turned up with his two tape machines and his guitar, we set it all up in the film room, and he gave us a free concert there.

For how many people?

There were probably about 30 in the record shop, and 50 in the school. That was a very important moment for me mentally—seeing this guy interested in making music, not just playing music on big stages as part of [King Crimson]. Then the art school had this fucking excellent idea of inviting Conrad Schnitzler to do a two-month residency as a kind of professor there. His contribution was setting up a sort of audio studio in his room and inviting all of the students to come around and experiment with the gear he had set up.

I was in possession of the same synths Conrad Schnitzler had brought along, so we struck up a good vibe straight away. I hung out with him the whole time he was there. He was not an outspoken critic in the sense of him saying we’re going to do this or do that. He just let me use a tape machine, and an echo, and a little mixing desk—stuff I’d only seen in photos before. In the end, a fellow student of mine and I decided we wanted to release the tunes that were assembled over those two months on a record. That was my very first record.

That was you and Holger then?

Holger was involved, but we didn’t actually do it together. We started talking about his plans to form a band about two months later. There was a big hitch because I wasn’t a musician as such. Holger was; he knew how to read notes, and sheet music. It took him a while to realize professional musicians weren’t that interested in what he was up to. They all thought that was too freaky and whatever. So he came back to me and said, ‘Why don’t you come around?’ That’s how the first single got produced with just the two of us.

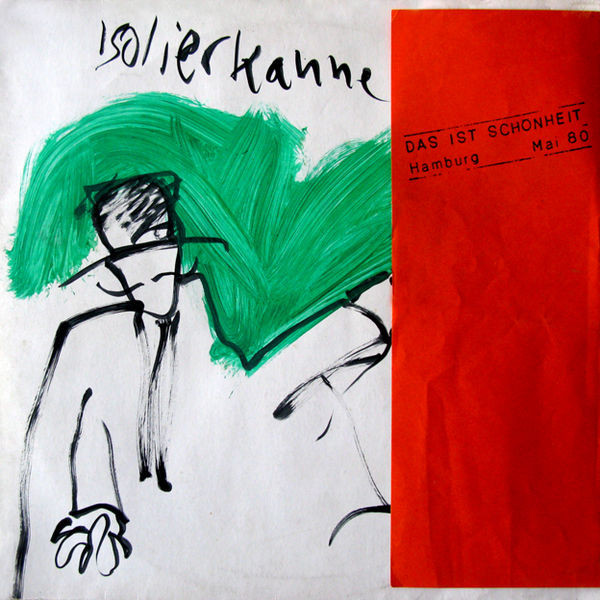

Who did you do your first record with?

Walter Thielsch. He wrote the lyrics on one of the tracks on the first Palais Schaumburg album, and he became the singer on the second album. He was responsible for introducing Holger to me, so in that sense, a very important person [laughs]. Walter and I also took on the challenge of painting the thousand covers of the first edition ourselves by hand.

Every single cover?

Every single cover. No wonder why they go for 400 bucks these days.

Did you hold onto a copy for yourself?

I have four.

So that’s your retirement plan?

We’ll see what happens.

So up until that moment of meeting Conrad, you hadn’t really experimented with music much yourself?

I was a guitar player, playing Neil Young songs, you know?

So you were more of a singer-songwriter then?

Yeah, well, I also liked to play the blues. Someone would play 12-bar blues for me and I’d solo on top of it. It was very wanky. I wasn’t too good at all, but it really entertained me and I entertained a few people around me too.

You must feel so fortunate to have grown up at that time, a time where Conrad Schnitzler happened to be teaching at your school, and Robert Fripp was open to playing a show for you.

Yeah, those early ’80s moments had a substantial impact on my life. And yes, I do feel fortunate to have experienced this phase of consuming music the way we did then. Going to concerts was a really special thing because they weren’t so common. It was something people looked forward to for months. And on the other side, I liked hanging out at record shops, and the inspiration that came from that.

It must have been exciting to go from watching Robert Fripp perform live for a small group of people to actually playing with him on a record.

That was certainly a high point. Absolutely. Not only that we did it, but that it turned out brilliant. I’m very proud of it. It was full circle for me in a way.

How did that record come together? Did you work together on the whole thing?

We did. Not so much in the mixing phase though. Robert was part of two big recording sessions. It was initiated by Alex, who worked at E.G. Records, the company Fripp was also on. It wasn’t a blown-up production thing. We just asked him if he’d be up for it, and then we made an arrangement to get together in the studio.

After the first initial meeting, Alex asked me to join. So I was part of the big recording session and the mixing stage of it. That was also the beginning of me working more permanently with the Orb. Then came Pomme Fritz and Orbus Terrarvm. I produced one track on the first record; on the second, I produced two tracks; and then I became a more permanent figure in it.

Did it feel like Alex was testing you, to see if you two worked well together?

That’s kind of the nature of it, but we were both excited to get together. Germany, at that point, still looked up to England, so it was nice to have a creative partner there. That has obviously changed quite a bit, to the better [laughs]. Alex also had a great respect for German music as well, starting with Kraftwerk, Krautrock, and all that stuff. It was a combination we both enjoyed a lot from the first collaborative tune “Outlands.” We felt it worked right away, and then just had to figure out how to get on a more regular exchange of ideas.

How would you describe your relationship back then and how it’s evolved over the years?

Well first off, an important part is we don’t live in the same city. We always make dates to work together, and then we actually work. We’re not hanging out; it’s quite to the point—’now’s our time, we have to deliver, let’s go.’ To this day, that’s how we work best. We’re always working together in the studio. We never exchange files. Alex regularly comes to Berlin to work in my studio. That’s where we produced the last record, Chill Out World. There’s an interesting element to it that’s dramatically different from the way I worked with Holger. Discussion was 50-percent of our process of making music together. With Alex, we barely have discussions. We just let go, and have big respect for each other’s musical input. We still find total inspiration when we get together. Like the new record still gets me going. I’m really proud of it.

Did you have sketches of different songs for this record at all? Or at least certain samples in mind?

Nothing. It’s totally blank. And always was.

Tell us about your half of the ambient mix we’re running today.

My part is the second half. I choice stuff that’s pretty current for me—things I want to hear. Not so much going into the history of it all, just looking for ambient things that have touched me in recent months. Even the Sun Electric stuff is a new one, an unreleased one, which they don’t do very often.

One thing I’d love to highlight is the Daniel Lanois track from his new record. That’s a super record. We met him at Moogfest in Durham a few months ago. I was well impressed to see him going grassroots as well, working with my favorite instrument of all—the pedal steel guitar—to do a very touching, emotional set. It let me forget all of the music he produced and I hate.