Words by Andrew Parks

A few months ago, we wrote something on our Twitter account just to fuck with people and prove a point. Sleigh Bells had just dropped the digital version of their debut, Treats, and far too many self-anointed critics had already made their mind up about the Brooklyn duo. On one side: the hype mongers, the ones who think Sleigh Bells are here to rewrite the rules and rewire the sound of pop music. And on the other: the cynics, the ones who think Sleigh Bells are yet another example of a blog-driven obsession with being “first.”

Outside of seeing them at SXSW and sending one of our photographers to cover their show with Surfer Blood last fall, we largely avoided listening to Sleigh Bells. At least until the pressure became too great and we caved in, firing up a press copy of Treats and finding it exhilarating but, well, really fucking loud. Or as we wrote into the Web’s vast void, “It’s giving us a headache. This would have worked well on Korn and Limp Bizkit’s Family Values tour in the ’90s, though.”

Sure enough, a fan of Sleigh Bells saw our tweet and forwarded it to guitarist/producer Derek Miller. He then responded to us, basically saying it’s funny that we’re slamming the record after asking to interview the band several times. We explained that we weren’t slamming the record, that we were just giving a knee-jerk reaction in response to all of the hoopla that was happening that week. As for us asking about an interview in previous weeks, the idea there was to discuss what all of this Next Big Thing nonsense means in the scheme of things, not feeding the blog-fueled beast even more.

“I don’t really like to consider myself an ‘artist,’ but we work in a creative field and are sensitive to that shit”

“It’s funny, when I saw your tweet, I actually thought to myself, ‘Yes!'” says Miller, when we reach him during a tour overseas, “We actually joked about being a new-metal band during Major Lazer’s tour. [Diplo] was like, ‘You guys are the new Limp Bizkit.’ And we said, ‘Yeah! We kinda are!'”

To bring that point home even further, Miller played the moronic Korn song “A.D.I.D.A.S.” (a.k.a. “All Day I Dream About Sex”) during a WFMU radio show.

“I’m not running away from any of that,” he explains. “Dude, I saw Korn on the Life Is Peachy tour in Orlando. I was 14 or 15, and it was one of the best shows I’ve ever seen.”

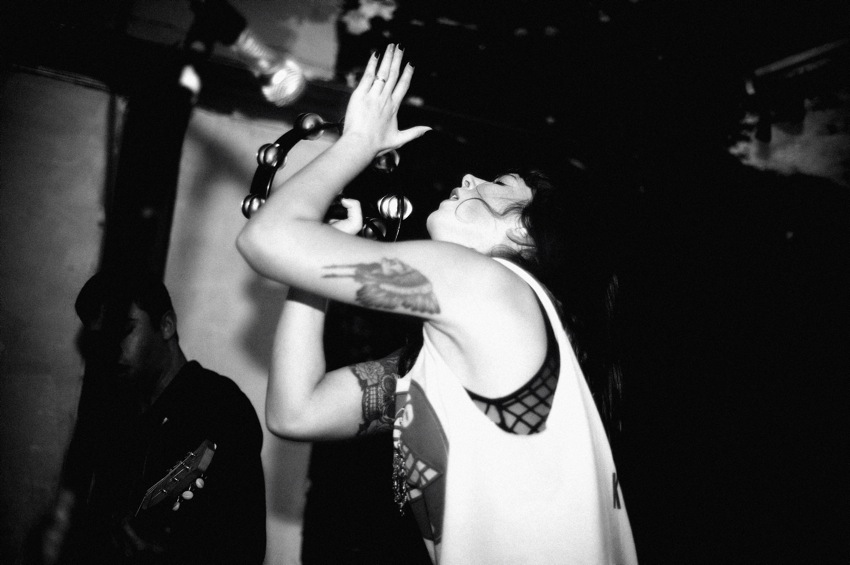

The lack of pretension in the music and general mood of Sleigh Bells is why we were ultimately drawn to them. Unlike their label boss M.I.A., the prickly pair knows they aren’t here to change the world. They’re here to deliver rock candy that’ll rot your speakers from the inside out, and to play shows that’ll reduce most rooms to absolute rubble, largely thanks to Alexis Krauss, easily one of the most exciting frontwomen in music today.

The following is easily the most extensive Sleigh Bells interview that’s been published yet, and the only self-titled feature that’s ever arisen out of a reported “Twitter feud.” So yeah–shit’s about to get real…

So are you ready to argue about how much we hate each other?

Yeah man, I’m ready for it. I’ve got my old Yankees cap out and everything.

Isn’t it a little weird how something so harmless can spread so quickly on the Web?

Dude, it’s kinda ridiculous. A couple minutes after [we talked], I had this funny exchange where someone was like, “Woah dude, this is crazy!” I actually deleted my Twitter app after that…

Yeah, I noticed you delete comments here and there.

We’ve been doing that since the beginning because we’re not huge fans of social networking sites. Any of them, really–like our MySpace has nothing on it, and I haven’t logged into our Facebook account in forever.

But you’re aware that’s how a lot of this nonsense spreads right?

Absolutely. It’d be ridiculous to pretend that I’m ignorant to it. The whole thing just makes me feel pretty uncomfortable. Something about it’s just really weird. First of all, I don’t see the need to tell someone whether or not I’m enjoying my hamburger. That’s just fucking ridiculous. There’s some value in reigning yourself in a bit and not getting on your knees at every opportunity for a little exposure. I don’t think it’s healthy for bands–for everything that’s good or bad about your band to be at your fingertips…literally. It’s terrible.

Right. As much as artists say that doesn’t influence them, it has to to some degree.

Yeah, man. I don’t really like to consider myself an “artist,” but we work in a creative field and are sensitive to that shit. We care; we want people to like what we’re doing. So [criticism] bugs us. Anyone that tells you it doesn’t is probably lying a little bit.

A lot of your positive press has been based on really backhanded compliments, too. Like the New York Times said, your riffs are “so audaciously straightforward they verge on brainless.”

Well, you know, critics have to be so on top of everything. We get a lot of ‘it’s like this meets this…but in a good way’. Or someone always has to mention how quickly this could all go away.

People also consider Sleigh Bells a guilty pleasure. I assume you don’t even believe in the concept of that…

Of course not. That’s ridiculous. I understand what [critics] are doing. That tone is so common, and so old, that we try not to take it very seriously.

So tell me a little bit about Alexis and her background in pop music–how it helped with your creative process for Sleigh Bells.

She used to do a lot of random session work, whether it was a jingle or demos that ended up going to Britney [Spears] or something. So she’s very patient. From a production standpoint, she’s good with abstract directions, like, ‘Okay, this has got to be sparkly’.

You used the word “sparkly” in the making of this album?

Sure. And you can use that against me. That’s fine. I deserve it. [Laughs] But yeah, it was probably a little embarrassing for her, because she was going out of her comfort zone. We were both vulnerable, and therefore, equal. It wasn’t too painful.

“You know how it is when you’re 15–that shit becomes your identity because it’s all your looking for.”

I love that you were literally going up to girls asking them if they were a singer, leading up to meeting Alexis. That did happen right?

Oh yes. As evidenced by me meeting her at a restaurant where I was waiting tables.

That happened when again?

November of ’04 was when I first started looking [for a singer] in earnest. I had just quit my hardcore band (Poison the Well), and moved from California back to Florida. I really wanted to work with a girl because I prefer female vocalists and had been surrounded by sweaty metal dudes for the past six years of my life. So yeah, it took a while. I moved back to California and played music with some friends. I never found anyone [for Sleigh Bells], so I moved back to Florida.

Were you playing Poison the Well-like music when you moved back to California then?

No, I don’t know what it was, man. It was all pretty mediocre. I was pretty dead-set on not contributing to the noise of another band. That’s just static. I’d rather be waiting tables. So anyway, when I moved back to Florida, I hooked up with some friends and a different girl, and it was good. Sonically, the material I was coming up with was closer to the standard of what I was holding myself up to. It was close, but not quite there. There was like a band version of “Infinity Guitars,” for instance.

This was when the Surfer Blood guys were in the band?

Yeah, exactly. They’re all old friends of mine. It was [Surfer Blood frontman] J.P. [Pitts], [drummer] T.J. [Schwarz], and JP’s sister. We played a bunch of music together for a while. It was pretty cool. I had my ideas of what I was trying to do, and they had theirs. It was all band stuff. I didn’t get into programming until I moved to New York. So I was mostly playing guitar, T.J. was playing drums, and J.P. was playing bass and singing. It was fun. West Palm doesn’t have much of a scene, so you usually end up playing together at some point and trying stuff out. It’s been cool to watch them get their shit together, make a record, and have everyone love it.

What part of Florida are you from?

I was born in Pahokee, but I was raised in Jupiter, which is an hour and a half up the coast from Miami. So I surfed a lot growing up, right up until I got a guitar and quit surfing to focus on that.

What was Miami like for you? Did it fulfill a lot of the girls-in-bikinis stereotypes?

Miami’s fucking diverse. Jeffrey [Moreira], the singer from Poison the Well, grew up in a tough area, actually. Jupiter was a small little beach town with nothing, really. I think we got a Taco Bell in ’91 and it was a huge deal. Like a lot of other parts of the country, there’s a real cultural void. My family’s still there, so I got back all the time.

Going back there must keep you grounded.

We don’t have any trouble with that. Not to be plain Jane or boring about it, but we’re extremely humble and critical of ourselves. I don’t need to go to a destination to feel grounded.

Well, it must be relaxing at least.

Yes. It’s super relaxing. My sister lives there with her family, about 200 yards from the beach, so I’ll just go crash with them, hang out with my niece and my nephew. It’s pretty dope.

Was Poison the Well an anomaly in your part of Florida then?

There were actually a fair amount of hardcore bands, mostly in, like, Fort Lauderdale. I was 15 when I went to my first hardcore show in West Palm Beach, at this place called Happy Days. And every once in a while, a band from Lauderdale or Miami would come up and just shred up the place. So the second I turned 16 and had a license, I was down in Lauderdale every weekend, for every show.

They were the cooler town then?

So much cooler. I don’t know if the music was necessarily good, but it was a lot better than what was going on in West Palm. So that’s how I got involved with the Poison the Well dudes.

And you were pretty much immersed in that music at that point?

Totally. That was the first exciting thing I’d ever found in Jupiter. You know how it is when you’re 15–that shit becomes your identity because it’s all your looking for. I don’t know if you’ve even been into hardcore.

I have, actually. I’m from Buffalo, so that’s all we had too.

Snapcase then, right?

Yep.

[Laughs] They were a great fucking band, actually–Snapcase.

Come to think of it, I may have seen Poison the Well when you were still in the band.

That’s possible–we played up there a bunch. Man, I’m still extremely close with the Poison the Well guys. They’re like my brothers, for sure.

“You just start thinking hardcore’s kinda ridiculous and restrictive–that you want to grow but your fans won’t let you”

What was the breaking point where you decided you needed to leave then? Poison the Well was getting more experimental around the time you quit…

I started becoming more controlling. You Come Before You came out in ’03, and that was pretty collaborative, but after that, I wanted to do everything. We all wanted to diversify the sound, but a lot of times, we spread ourselves a little too thin.

Looking back, we were a pretty cool hardcore band when we were being straightforward and heavy. I feel bad saying this, but a lot of the melodic stuff we did is pretty fucking corny. But it’s where we were at. What the band used to be disappeared, and when one person is doing everything, all of the sparks go away. It wasn’t like a really shitty split. There were no fights. I was just unhappy. Everyone knew that. My involvement with the band had run its course.

As a listener, were you drifting away from that music, too?

Totally. All of us were, around ’01 or something. Once you hear something like OK Computer, it’s like, ‘Wow!’, and then that leads into something like Björk, and so on. It’s all just a gateway into something other than just Converge records. Then you just start thinking hardcore’s kinda ridiculous and restrictive–that you want to grow but your fans won’t let you.

My personal turning point was going to see Hellfest in 2003. Metalcore–that style Poison the Well helped pioneer–was becoming really trendy and watching that for an entire day made me want to kill myself. It was just the same…fucking…band, over and over again. Which must be what touring felt like for you towards the end–just really repetitious.

Absolutely man. I had wanted to leave the band for so long. It wasn’t a snap decision. It was a long time coming. We had been doing it since we were 16. Not to be all fucking misty-eyed about it, but we were a family. It was also my job–what fed me and paid my rent. And since I didn’t have any savings, I had to be ready to wait tables once I left. I just knew that if I wanted to move forward creatively, I needed to make that break. The sooner the better.

You’ve gotta push through all of the shit, all of the mediocrity. I feel like that’s what I’ve been doing for so long. Sometimes I’m afraid that I’m still doing that.

What do you mean? That you’re always second-guessing yourself?

Yeah, like with a lot of musicians, everything’s exciting when you’re in the moment, but the second it’s done, I start to hate it. I’m not there with Treats yet, but I know that after a year of playing it, I’m never gonna want to hear it again. I already want to get back into the studio, because we have so many new ideas. I wish I could live there, but now’s where the real work starts.

Is part of the problem that you’re worried about this ending any day now, because things move so quickly now?

No, I actually have a lot of faith in the material’s ability to stick around. I really do. That’s the only thing that saves a band from a hype cycle–does a record actually resonate? Is there anything exciting or memorable about it? For me, it meets that criteria. I don’t think it’s that great, but it’s the best we could do. And I’ll stand behind it.

Well, one of the best decisions you made was to produce it yourselves. I feel like one of the selling points with your label was the way you sound–that it’s this kind of anti-pop music.

Yeah, we spoke to a lot of labels and whittled it down to people who wanted to facilitate what we’re doing and trust our artistic decisions. It’s ridiculous to me that labels actually work with bands that they don’t trust creatively. When we were wrapping the record up, I actually wanted people’s opinions on the mixing and the mastering because they’re not just label jerks. They’re really good dudes. Michael Goldstone at Mom & Pop has been involved with some really great records, you know? Like he signed Rage Against the Machine and Pearl Jam. And then there’s Q Prime [Management], the people who back the label. And of course, Maya (M.I.A.). At the end of the day, we go with our instincts and they say, “That’s good; you guys know what you’re doing better than we do. That’s why you’re the one making the records.” I can’t really ask for much more from them.

Well, you’re an artist that essentially makes them look cool, too.

Sure, although I don’t think coolness isn’t a currency they trade in. Alexis and I aren’t really cool people. We’re too honest for that. And those dudes aren’t super hip, either. It’s not like we’re working with Pedro Winter from Ed Banger or something. It’s…different. [Laughs]

“Since it’s M.I.A., we thought they’d listened to it through a huge sound system. But no, Spike played it for her through his iPhone.”

So when did all of this label attention really start?

Maya got involved in September. The only people who were listening to our band then were our initial circle of friends. We’d played two shows…

Who were you hanging out with then?

No one “of note.” My oldest and best friend is a guy by the name of Will Hubbard. He now co-manages us. He’s actually the one who got me to come up to New York. Will and I have known each other since we were 13. He’s my best friend and a smart guy, so I trust him.

Was he involved with Poison the Well at all?

No, he was teaching at NYU for a while and really grounded in academics. I sorta sidetracked him. He was like, “You can throw a rock in Brooklyn and hit an idiot musician. Just come up here and start looking for people. You’ve been in Florida for a year and don’t have anything going on. What do you have to lose?” So that was a huge help. And as we got our shit together slowly, it made sense [for him to be our manager]. He co-manages with a guy named Bill Folds. I’ve known him for 10 years. He worked with Poison the Well forever, is a little older, and has a shit load of experience….

But anyway, I’m going to go back to the original question, about our circle of friends. That included a girl named Molly Young. Molly is a friend of mine now, but she was originally a friend of Will’s. She heard our music through him, loved it, and wanted to write about it for Spike Jonze’s Where the Wild Things Are blog. Spike and Sasha Frere-Jones–another early supporter–both heard about us through Molly’s post, actually. So Spike liked it, and wrote us an E-mail saying he might want to use the demos on a future project. That was so encouraging, because I love what that guy does. And then a week later, we got an E-mail out of the blue from Maya. I still have it. In all-caps, she was like, “HEY, I’M SITTING HERE AT MY HOUSE, AND SPIKE JUST PLAYED ME YOUR SHIT. I LOVE IT. AND I WANNA SIGN YOU.” She didn’t beat around the bush.

It’s funny because we were wondering how she heard it–the context and the sound. Since it’s M.I.A., we thought they’d listened to it through a huge sound system. But no, Spike played it for her through his iPhone. She literally showed up in New York unannounced and said she wanted to go into the studio after that. It was intimidating, but I was up for it.

“It’s so unpretentious and single-minded in its goal–just so skeletal”

It was bad enough when you had limited equipment with Alexis, but you must have felt especially intimidated at the prospect of working with M.I.A.

Yeah, it was a major turning point I was totally unprepared for. But it worked, it contributed to the sound and the creative process. You realize that people like her are actually looking for that.

Did you have a lot of ideas for her before you went into the studio and worked on M.I.A.’s record?

I had a bunch of beats, some of which I didn’t think would work with Alexis, and some that I did want to use with Sleigh Bells. She came over on a Sunday, on her bike, and listened to it all–picking out parts that she liked about different songs. Man, I thought she was gonna come by in an armored car or something. I’ve seen people with less interesting careers walk around with bodyguards, you know? So I didn’t know what to expect with her. It was really cool.

So she selected some sounds and then…

We went into the studio the next day. We had a week booked, but we were there for three or four days. They were pretty long sessions, especially compared to Sleigh Bells. It really fried my ears because I work at a really high volume and can only take it for like six hours at a time. We’d have to go home because we couldn’t hear anything after a while. The song I did on her album is called “Meds and Feds.” We were supposed to get together to do more, but the timing never happened. I’d love to get back in the studio with her, because it’s amazing to watch her work.

The Sleigh Bells sound came out of working with simple equipment to some degree. How did you approach going into the studio, when you could have fleshed it out with so many other instruments and techniques?

I generally have a very clear of what I want, so the main process is digging through sounds. Like I know I need a clap, snare or kick, and I have 900 to go through until I find the right one. That’s how most of the days were–getting into the studio around 12 and then just triggering all of [the samples]. A lot of, “Nope. Nope. Nope.” I remember turning to [engineer] Shane [Stoneback] and saying, “Is this okay? Are you going to pull your hair out?” And he was like, “Dude, this is normal. This is what production is like.” He definitely had a big impact on the record, sonically and technically. I hate working in Logic and Pro Tools because it involves sitting at a computer and can inhibit the creative process. So having an engineer that works like lightning was huge.

And Alexis could adjust to your ideas quickly too?

Yeah, she was so quick. It’s amazing. She showed me up every time.

What were some breakthrough moments in the studio?

“Tell ‘Em” was one of our first collaborations. I had no idea what to do with it. I was just like, “Okay, here’s this double kick pattern and these guitar harmonies…I don’t know where to begin.” And she was like, “Oh, it’s just simple,” came up with the melody and I loved it. That was a definite a-ha moment.

Did she tell you about her pop background right away?

Yeah, the night I met her at the restaurant, she went home and E-mailed me immediately with some of the tracks she’d done. They were like Kelly Clarkson or something, though, so she said, “This is not indicative of what I want to do creatively, but this is my voice.” It was exciting–vocally, she’s just do diverse. I didn’t feel like we’d hit any walls.

And because of that range, there’s so many other types of records you could do, right?

I don’t see any end to it anytime soon. I feel like we’re just getting started. “Tell ‘Em” and “Riot Rhythm” are our two newest songs, and they came together the quickest. I really like “Riot Rhythm.” It’s so unpretentious and single-minded in its goal–just so skeletal.

That’s why people love the band–because it’s so minimal.

I hope so. That’s what I wanted to do so badly. I throw a lot of shit away, which can be disheartening. You can write 50 bad songs in search of that one good one. It can make you feel like a total failure, a total fake who has no talent–knowing about those 50 godawful ones no one else has any idea about.

Either way, the record’s out there. It is what it is. I don’t know if it’s good, but I do know it’s not terrible.