Words by Trevor de Brauw

Now that Neurosis is considered one of modern metal’s most influential acts (see: such vocal supporters/acolytes as ISIS, Mastodon and Converge), it’s easy to forget their hardcore/punk beginnings in the same Bay Area scene as Operation Ivy, Crimpshrine, and Blatz. In fact, Neurosis’ meditative approach to heavy music didn’t emerge until the quintet’s third album, Souls at Zero, a journey to the darkest fringes of psychedelia that incorporated an arsenal of keyboards, samples and complex arrangements.

And then there was its follow-up, 1993’s Enemy of the Sun. Recently reissued on the band’s own Neurot imprint in honor of their 25th anniversary, it’s a sonic manifesto of sorts, embodying the many qualities that people now associate with Neurosis and their many followers: trance-inducing repetition, a masterful command of dynamics, and an oppressively heavy sound that’s downright spiritual in its scope.

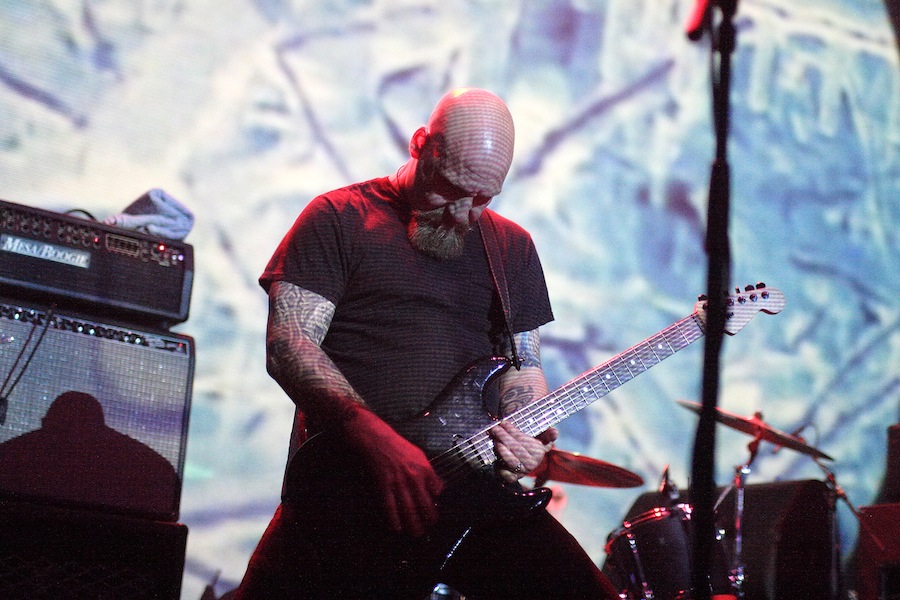

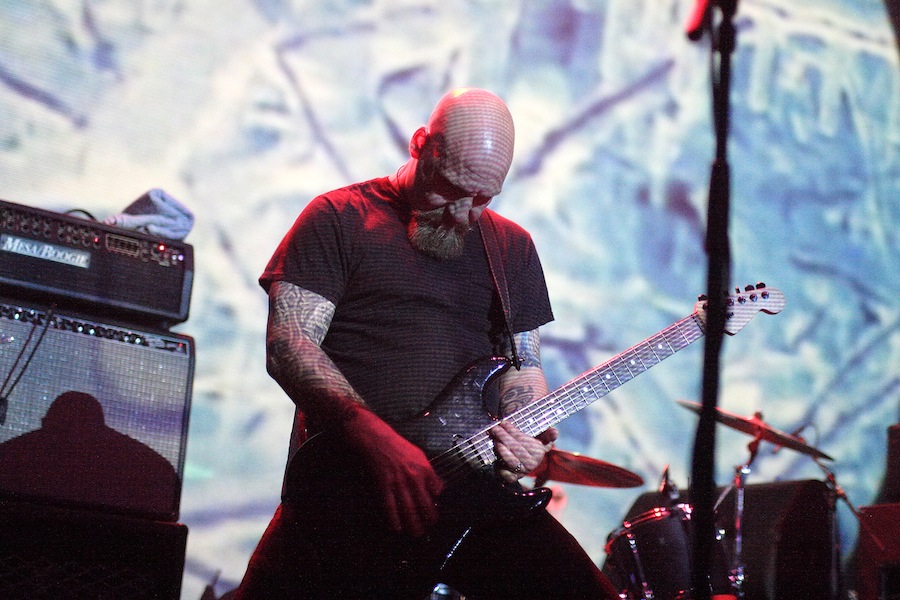

To get an idea of what brought on this crucial stage of Neurosis’ development, self-titled tracked guitarist/singer Steve Von Till down for a rare interview.

“Some of those really older ones are uninspiring to bite into because we’re not as excited about that music anymore”

self-titled: First, I want to congratulate you on your 25th anniversary. That’s quite a milestone.

Thank you. In many ways it’s just another day for us. I mean, we can’t envision our adult lives without doing what we’re doing. But then you put it in musical history context and it’s a fucking long time.

At the same time it’s seems like…I don’t know if it’s just now or what it is, but it seems like there’s more than a handful of bands that have stuck it out. I’m thinking of the Melvins and some other folks. You know, we can’t give it up.

I think it’s testament to how dedicated you guys have been to a certain aesthetic. Your music seems timeless and driven to chart its own path and nothing can really stand in the way of that, whether you’re doing it now or 30 years from now. Which draws me to what I wanted to talk about–Enemy of the Sun. Is there a particular reason you chose that record to reissue for your 25th anniversary?

Not really…I mean, the conversation came up whether we should do something for the anniversary. The bottom line is [that] preconceived things like that never work out for us. We just have to go with the regular flow of things as they come. It’s just the reality of the way we work.

The way the timing of the reissue of Enemy of the Sun came up–and Souls at Zero will follow early next year–is just kind of a re-dedication to the label at this point. It coincides with some European releases we did. In America, Relapse has a couple of our records, Through Silver In Blood and Times of Grace, but our contracts expired with our labels in Europe, so we had this unique opportunity to revisit a couple “classic” Neurosis records. We had Josh Graham, our visuals guy, kind of redress them a little bit. Not really mess with the original artwork or symbols but put them inside an o-card with a recurring theme and recurring color scheme…an aesthetic decision really, because when we first started the label we didn’t even have a label logo or anything like that. I look at those older pressings on the shelf and it doesn’t really tie in.

Also, to be perfectly honest, in the days of Souls and Enemy, it was the very first era when we were using computers instead of films to do the artwork. A lot of the old artwork was saved to multiple floppies–the most recent thing it was on was a Syquest drive–and a lot of the data was corrupt or missing so there was no way to recreate the original artwork the way it was anyway. So it was a good kick in the butt to revisit the stuff.

Those were the first things Neurot did, right? Souls At Zero, Enemy of the Sun, and Pain of Mind? Or did you do The Word as Law?

We didn’t do The Word as Law. We can; we just haven’t gotten around to it. Some of those really older ones are uninspiring to bite into because we’re not as excited about that music anymore. For the sake of the catalog, we’ll probably revisit it at some point.

“We realized that we weren’t in control of it, that the secret to getting there was total surrender”

With Enemy of the Sun, it feels like you really came into your own as a band. From that point on, the records seem to embody a similar aesthetic. Did you feel like you aware of that at the time?

I think that only comes in retrospect. I mean, Pain of Mind was just hardcore teenage angst–just “this is what we can do.” There was a thread of something more psychedelic, but there was no tangible way to grab it. We had no idea how to get there. With Word as Law, we were struggling to try to find it. We were hearing something else, but we just couldn’t capture it. And with Souls at Zero,we added keyboards and samples and were a little more comfortable in a recording studio. We got amplifiers that we were jiving with and started to get the tones different and play with different tunings. There was a gut instinct driving it, but there was a cerebral thing getting in the way of achieving what we wanted to. We were struggling with the mind part of the music.

Like you knew what you wanted, but you were thinking too much about how to get there?

Yeah, we were getting stuck in these technical things. Touring the Souls at Zero material was where we started to realize that it was all about flow and all about these movements instead of arrangements; an energy flow rather than technicality. And we started to experience some–for lack of a better term–spiritual and mystical moments of trancing out in the music. And it happened in certain parts more than others. Enemy of the Sun is where we really figured that out, I think. We were starting to compose music that was predisposed to that because we were experimenting more at the rehearsal space with losing our minds and just, you know, going off on these strange textural tangents where the energy that we could picture–the epicness we could imagine–was starting to feel like it was flowing through us. We realized that we weren’t in control of it, that the secret to getting there was total surrender.

Was this something that you guys talked about at the time or was it kind of implicit?

It was unspoken. Again, I think it was something we learned over the years following. We started to unravel that it was a force bigger than us and it’s only when we put ourselves completely aside that it worked. Because the mind gets in the way. It might work for other peoples’ music, but for what we were trying to do, we had to get out of our minds and just let it feel like it was the weather or something flowing out of the earth and up through us. We had really nothing to do with it except to be a conduit. That was, I think, Enemy‘s huge revelation to us.

At that point were you guys incorporating visuals?

Yeah, I think we started that at the same time we did the keys in about ’91-’92 with Souls.

“And that was, short of doing some sort of ’60s acid test on them, to enter their psyche through their eyes”

I take it that the idea behind the visuals is to take the audience on a trip, in a way. To take people inside of the music so they can lose themselves there. So it seems like, whether it was spoken or not, it was something you knew you were going for, but you hadn’t exactly figured out how to get there.

You can’t say that the visuals were intuitive because you can’t sit around and jam visuals, you know? That was a specific strategy. That was like, “Okay, how do we make any space we play our own? How can we go to all these millions of different clubs that all have their own energy and how do we make that a non-issue? How do we make it our own place?” By, one, getting the lights down low. I was in school at the time, taking quite a few psyche courses and I remember studying Jungian philosophy about archetypes and reading a lot of Joseph Campbell stuff about myths and it all came together in this strange psychedelic collage where it was like, man, maybe we can use this. Almost the way Throbbing Gristle talked about using certain frequencies to elicit an emotional response.

And this was before the hypermedia age. I think we’re probably too rebellious by nature to conceive of that idea now because the whole world is so visually oriented, but back then it was, like, “What if we could rapid fire all this gnarly shit–vivisection, concentration camps, war, psychedelia, art films–to where it actually breaks down peoples’ defenses, and they have no choice but to surrender?” If you’re gonna wrap your mind around that–with five freaks going crazy in front of all this stuff–you’re not gonna like it. You’re gonna leave and you’re not gonna feel very good. You know, it’s not easy for the listener. If it somehow could help bring the audience to where we get to, which is…you know, we get there by letting the music go through us. We’re creating and disseminating it, so it’s a little easier for us to lose it. So how do we get the audience into the same frame of mind? And that was, short of doing some sort of ’60s acid test on them, to enter their psyche through their eyes as well. And if you can break down the defenses, maybe they would become more susceptible to have some sort of unique emotional response–a unique emotional feeling that, whether they liked it or not, they weren’t going to forget it once they left the concert. And I think that worked.

Were you guys touring a lot during that time? Around Enemy of the Sun and Souls at Zero?

Yeah, I think so. Maybe a few months out of the year.

What did you guys have going on outside of the band? I’m just curious because I know that living off of a band means having to tour all the time and if you have to work outside of the band to make ends meet you can’t tour that much. Which is more like where you guys are at now. You guys do like two weeks to a month per year or so?

If that, yeah.

“The fact that anybody likes self-centered music like ours is a complete mystery sometimes”

So when I hear you say that you were touring a couple of months out of the year it leaves me a little bit curious what your personal lives were like off of the road. What were you guys doing outside of the band?

It was different for everybody. I mean, there were already children. There were children in Neurosis when I joined, which was late ’88, early ’89. So there’s always been the obligation to family. Actually the time period of Through Silver in Blood to Times of Grace was when we hit the wall with the insane touring. Like, “Hey, can we not have to come home from our summer where we quit our job and can we try to make a go of it and tour 200 days a year?”

So back then–the Souls/Enemy era–was like, people were going to school, people had jobs, people had families. So struggling with all those things but from the younger mindset. And as we got older and tried to earn a living off it, we just realized to get out there and play that many gigs [that] there’s no security in it–one guys breaks his arm and you’re all fucked. And we had that happen a few times. You’re not investing any money and you come home for a month and the money still runs out and you gotta go dig for some shitty job, even if it’s part-time work. And so it seemed like it made more sense that since we loved this and wanted to do it forever, rather than burn out and go on too many tours where, okay, we enjoyed the headlining tour in these six cities out of 25; and we went and opened for some shit band for two months cause it seemed like a smart thing at the time; and–no regrets on any of it–but it seemed like there were compromises on the horizon if you were gonna do that.

And it’s fringe music. It’s fringe music–you’re never gonna cross a certain threshold and there’s no plan or…all that stuff happens by luck. The fact that anybody likes self-centered music like ours is a complete mystery sometimes. Like, “How does anybody else like this?” [We] just feel fortunate that they do because the ego strokes feel nice–they’re not necessary but, you know, they feel good–and they kind of justify all the effort you have to [put in to] get it out of your garage and out to the world. When you look at it more like a treasured hobby, it’s something you’re driven to do with a passion and you can find balance in your life with it. Especially when you have children and you need to be a proper parent. I balance it with running the record label and teaching. And I enjoy all of those [things] and I do all of them with a passion and I wouldn’t trade any of it. I get to be home with my kids. I’m not out there in Salt Lake City on a Monday night thinking what the fuck am I doing here? I want to be home with my girls, putting them to bed, reading them a story. It just takes the pressure off. Art and commerce are strange bedfellows and they don’t really jive at the very core of what they’re there for–they don’t meld.

It’s a complicated business.

Yeah. Business wise, it’s a stupid business. You want to make money, get into a different kind of business. You want to do this because you’re driven to, and you have a passion. Put your heart into it and do your best.

Getting back to Enemy of the Sun, you were saying that with Souls at Zero, one of the things that marked that time and marked the changes in your band was that you were becoming more comfortable in the studio. Enemy of the Sun was your first work with [producer] Billy Anderson right?

Yeah, we did two records with him. That and Through Silver…

How did you come to meet him?

He was doing live sound at the Kettle Club, which was one of the first bigger 21-and-over clubs that we’d played in San Francisco after playing the warehouse/party punk rock/teeny bopper scene. And he had recorded the Melvins. He was working in a couple cool local studios, and we didn’t have a lot of studio experience, you know. It was like, “Man, we gotta get into a recording studio,” and we just didn’t know where to go. Our first couple of experiences were like finding any old engineer dude and just basically believing whatever he said and not understanding how it works ourselves, and we were not really happy with how the first couple records came out. Souls at Zero came out a lot better, but there was still some shit that we were doing–we just didn’t know better. And Enemy of the Sun along with, you know, feeling comfortable in that kind of sound and that vibe and feeling the flow, um, it was our first time where we basically just set like we were set up in our rehearsal space and just baffle it up a little bit to get some separation and just record. Record live, you know?

Holy shit. That’s kind of nuts.

And of course you overdub the vocals because you want to get a good vocal performance, but basically guitars, bass, and drums are all done as a band. We got away from that again in Through Silver in Blood a little bit because we wanted to play with double tracking, which was a mistake, but basically all our records after that are all done live except for the vocals. We set up, we mic up, and we play…

I don’t want to cut you off, but do you think that Through Silver in Blood doesn’t sound as good as Enemy of the Sun?

It’s hard to say. I mean, I don’t even listen to these records. I think Through Silver in Blood has its own kind of unique twists and tweaks to it. I think that we labored over it more than we had to. I think we coulda done it the way did before and the way we did after. It was a bit of a tweak-ville situation.

But Enemy was very natural, and in fact, we went in thinking we were going to record an EP and we were so jazzed from getting all the songs down in two days that we went back to the rehearsal studio, improvised some shit real quick, and got some stranger things we were working on and–again, I think realizing we didn’t have to overthink–we could go with our gut and let the music flow through us. This stuff was inspired right then and happening. We went in and came up with a few more ideas a few weeks later and finished it up and it came out really cool. It was just a really good experience. It was old school mixing, you know? Where there’s no automation; there’s four guys standing at the desk doing all the moves. It was really gratifying. It felt really good. I think everything about that era for us was gelling.

Yeah, actually you touched on something I was gonna ask about, which is that the shortest gap between albums in your entire discography was from Souls to Enemy–only a year–but it makes sense if you had gone in to make an EP.

Yeah, it was really flowing. And Souls at Zero was also recorded…you know, we’d been working on those songs for awhile, so by the time we got that record done we had already had a few of the ideas sitting around. Yeah, that was a strange thing how short that came cause we tend to be a little longer in the process.

Yeah, but that’s amazing. It must have been a really killer period creatively.

Yeah, totally. We had our own warehouse space. A couple folks were living there and it was just always available. And we were just really excited by what we had just stumbled onto, and the fact that we had had it in the back of our minds for so many years but didn’t know how to get there and it finally seemed like we’d cleared away the brush and gotten enough experience to recognize the path. Like you said, even though we’ve evolved and changed and things are different each time since then–that really shows the clarity of the path at that point.

Yeah, it’s kind of like you guys laid out the blueprint and took it from there.

Right.