Wayne Coyne ponders life, liberty and a big fucking gas tank

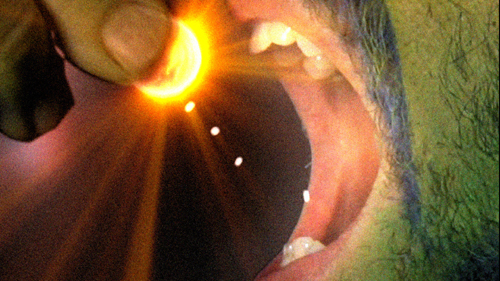

[Photos courtesy of Cinema Purgatorio]

Interview by Andrew Parks

While self-titled already told you what we thought of Christmas on Mars–Wayne Coyne’s mind-fuck version of It’s a Wonderful Life–the thing didn’t quite hit us until a few days after we experienced its mix of marching vaginas and spot-on Adam Goldberg appearances. That’s why we got a hold of the Flaming Lips frontman soon after the film’s initial screenings–to ask him, “Why, Wayne, why?”

What we didn’t expect was for the poor guy to say he’s been dealing with house renovators at 6:30 a.m. for the past week due to the fact that he filmed most of Mars in his backyard and goddamn living room.

“I have this weird little art compound here,” says Coyne, “where my Flaming Lips roadies are always working on some project. It just never ends here.”

Indeed …

self-titled: This movie has been your baby every step of the way. That’s nothing new for you guys though, is it?

I know the word DIY gets thrown around a lot and that people think, “Of course you do it yourself, meaning you hire some people to do it for you.” But our work is [a DIY project] in every sense of the word. Maybe I’m a control freak and just don’t realize it, but I want the Flaming Lips audience to know that I’m doing this for them with as much care and attention to the aesthetics as I can. Virtually anything you can spend money on I’m doing it myself. That’s just the way my life is, though. We’ve been doing this for a long time.

Have the last six months been especially stressful, as the movie finally got finished and you had to rush into doing interviews, a new Web site, the DVD :

This part has been the worst for sure. Hold on a second. [Dog barks; Wayne leaves to answer door] See? It’s a madhouse around here. Anyway, in a sense the stress of not knowing if what you’re doing is working, that’s over with. At least I know the movie’s done and it communicates what I want it to. Whether people like it or not is a different story. All these other things, from T-shirts to the Web site, are there just to promote the idea that’s out there.

What did you want this movie to do? I was expecting some serious David Lynch-type shit, where I don’t understand anything that’s going on, but there was a clear storyline to the movie. It’s a little bizarre visually, but there’s still a structure to it.

That part of it surprised me as well. As you get into moviemaking and storytelling, it all seems like an impossible dream. Only because there are so many movies that cost $100 million dollars and suck. It’s like they have all these money, all these actors and shit, and the thing’s unwatchable. Since we’ve always made music videos, I knew we could do the latter of what you’re talking about–we knew we could make some cool visual shit that you could take LSD to it. But in the end, we’re really telling a story here.

Tell me a little bit about the space station. You built a lot of it at your house right?

Yeah, I was partially inspired by the differences between the U.S. space program and the Russian one. The Russian space station was not designed to be sexy; it was just very practical, so that part of it always appealed to me. There’s something bleak and humanistic about not trying to impress us with something’s sleekness. I like the idea that [our] space station isn’t some triumphant leap for mankind. It’s as if the [space crew] was simply forgotten, as if the budget had run out on the station in the same way it had run out in my movie.

Anyway, I went down to a cement factory and redid some of it to make it look futuristic. The rest of it was left alone, with the roof collapsed in and trash everywhere. That was always part of the concept: to have sleek parts placed right next to blown-out, dilapidated hallways and shit.

How much of the movie was shot in Texas? Most of it was done in Oklahoma, right?

We only did one scene outside of Oklahoma City–the one with Adam Goldberg inside the psychiatrist’s pod. He was down in Austin premiering one of his movies at South by Southwest, so I built the set for him right down there as a matter of convenience for him. He’s a jumpy character so you’ve got to fucking get him when you can. The rest of the scenes were done in my house, which is still a sprawling, open-ended compound. A lot of it was done in my backyard too. As the years went by, I got this big garage area in the back of my house that was turned into three or four sets. There was also a crack house directly behind me that I bought, gutted and turned into a set.

Weren’t a lot of the interior space station shots inside a 10,000-gallon tank or something?

They were. Let’s say you’re pumping gas. Well, that gas pump is connected to a big canister that’s buried underground. In the ’70s, those were made out of fiberglass. When they decided they didn’t want to use [the fiberglass ones], this guy in Oklahoma City dug them all up. So there’s a field in the south part of Oklahoma City where about a hundred of these are sitting, deteriorating at different levels. I went down there in 2001 and thought, “You know I could use these things for my space tunnels.” I called up this guy and told him I wanted to use the tanks as a space station hallways in a movie that I’m making and he said, “Dude, that’s what I’ve been telling people these things should be used for all along!” I expected him to say, “What the fuck is wrong with you?” And instead he brought one to my house in the back of his truck for $300. You never know who you’re going to run into.

Did you agree on a budget for this with Warner Brothers? And if so, did you stay within it?

We originally wanted to put this out in 2002 or 2003, right after The Soft Bulletin, which came out in 1999. But then we started working on Yoshimi after we’d started Christmas On Mars, without knowing the fate of that record. I don’t know if we had a budget in mind. With records, we usually ask for a couple hundred thousand. It doesn’t mean you’re going to get all of that or spend it, but you can start working with that in mind. We can do things that cost $10, $20 or $30 thousand dollars and not have it be the end of the world, you know? So I’d go and do a shoot that’d incorporate several different scenes, knowing that it’d cost $30,000 or something. By the time we got done, Christmas on Mars probably cost half a million dollars.

When did the project honestly get finished?

The major filming, with a crew and lights, was completed around 2005. But me and [co-director] George [Salisbury] were still doing pickup shots up until April of last year, like me walking down a hallway in a Santa suit or a certain special effects shot. We did some filming even while we were editing and putting sound down at Dave Fridmann‘s. I originally grew my beard and mustache for Christmas on Mars. I kept it all this time, knowing we’d need to re-shoot some scenes, so now I can’t change it because everyone knows me as “that guy with the beard and mustache.”

The more I learn, the more I realize that all movies are a calamity. We didn’t know that in the beginning. If we had, we’d probably be disheartened by it all.

Have you kept some of the set pieces up at your house?

A lot of the set got destroyed as we went along and needed to set up other scenes. I did keep the big 10,000-gallon tank and a few other things for fear that something is going to happen. But now that it’s on DVD, I feel like I’m out of the woods, although I don’t think I’ll be able to make a movie in my house again. My wife said, “Look you can do this one, but that’s it.”

Frankly, I don’t want to make another movie like this, where I have to build every set myself. Well, I say that now, but who knows?

Was the set done out of necessity or because you actually enjoyed that part of the process?

It was a little bit of both. I didn’t realize how much my take on building the set would influence the way we made the movie. There’s a million things happening when you shoot a scene, most of which you don’t notice right away. In the beginning, it was definitely out of necessity, though. A couple years into it, I had some guys help me make the set, so it wasn’t overwhelmingly. But in the beginning I would buy paint and a bunch of shit at Home Depot, then go to work with that and some glue. It was awesome.

I realize this is a loaded, open-ended question, but what have you learned from making this movie? I mean, it took you a good seven years to finish.

When people believe in me–not just Flaming Lips fans, but the people who have to actually work with me and follow my blind intuition–they’re allowing my subconscious obsessions to guide us. That’s something I wouldn’t have wanted to admit in the beginning, not when all of this money and work is pinned to such an abstract experience. Why would I make this movie? I don’t even know why now that it’s done. In the beginning I did. Art almost always diminishes when you invest so much money and time into it. It almost always gets rationalized or normalized; it takes the easy route rather than the fucking bizarre, unspeakable one.

As far as the Flaming Lips ‘philosophy,’ there is the idea that you do create your own happiness, your own thing that you love in this world. I used to not know that for sure. We don’t need a president to be elected or for god to help us, or for a scientist to help us. We have this power within ourselves to make this world work for us. Which is really what the characters in Christmas on Mars are doing. They realize they’re helpless, but in the end they realize this really is a wonderful world, no matter how dilapidated, dangerous and uncertain it is. Christmas on Mars is evidence to me, proof that this is true.

That things aren’t that bad?

That you make your life. You have the power to make your life epic, beautiful and happy regardless of your plight. I hate to say it, but I go to a grocery store where the woman at the checkout counter has been burned–her whole face and everything I can see of her. I don’t know her and I don’t speak to her about it, but I’ve been going to this grocery store for three or four years now, and every time I see her, she isn’t hiding because she’s in pain or deformed. She stands there, says hi, checks me out, and I go on with my life, and she goes on with hers. She could be saying, “I don’t have a life because I can’t enjoy it the way normal people do,” but she doesn’t.

I tell this story a lot, too. We live in a city that has a lot of stray animals. And my brother picked up a stray dog that got hit by a car. He took this dog to the vet and the vet chopped his one leg off, sewed him up, and within an hour of my brother bringing this dog back to his house, this dog was running around with three fucking legs, as if it was the greatest day this dog ever lived. Some people would say what’s a dog’s life if it can’t run, eat or fuck a dog once in a while? What … is … it’s … life? And I’d say, you know, you’re right. But this dog had three legs and he was living his life like any other dog. We should be like that; we should be able to take the things that happen to us and figure out a way to be happy.

Wayne, with a severely disturbed Steven Drodz

Is Steven’s character a projection of your own views on life, then?

Because we work so closely together, there are elements of each of us that are alike. Everyone involved in this with me essentially believes that these things are humanistically true. That’s why we’re friends, and why we work together. Otherwise, we wouldn’t even like one another. For instance, I wouldn’t hang out with a member of the Ku Klux Klan simply because I don’t like them.

A lot of the themes in your music are certainly mirrored in this movie.

People pointed that out as we made it. They’d be like, “Wayne you don’t even realize it, but you sing about moths in songs and you’ve got moths in your stupid space station.” “Well, yeah.” Or, “You sing about babies all the time, and here are babies in your stupid movie.” “You sing about outer space in every other song; no shit you’re gonna make a space movie.”

I always think I’m presenting some new idea. But everyone’s always like, “Yeah, we’ve heard it all.”

Well there are a lot of heavy topics in your music and this movie, but both still manage to be uplifting in some way.

I agree. On one level, the Flaming Lips sing almost exclusively about death, which points to everything optimistic and good about life. I mean, our publishing company is even called Lovely Sorts of Death. It’s taken from a hokey LSD reference, but I always knew this was what we’d sing about. That said, we always turn it into a celebration of life. I’m an old person singing about normal things, you know?

When was the first time you screened the film? Just for friends and family in Oklahoma?

We knew back in May that we’d have to screen it at the Sasquatch! Festival in Seattle, so I started to put the soundsystem together then, and before that was completed we started having screenings to test it out.

As for Sasquatch!, you don’t know how relieved I was to see people clapping and laughing along with the film there. I got the sense that people understood it and had some sort of emotional reaction in the way we were hoping they would. It was a nice focus group for us, because if it missed the mark with a Flaming Lips audience, then I obviously missed the mark completely. If some film critics who don’t know the Flaming Lips said “What is this piece of shit?” I wouldn’t care that much. I’m not trying to be the greatest filmmaker of all time. I just want the people who’ve believed in me to like it.

What are the chances of you still screening this thing with snow machines and that sort of thing?

I tried some of that here, and I think it’d only happen after more people know the movie enough. When I experienced Rocky Horror Picture Show for the first time, I didn’t know what the fucking movie was because I was pelted with so much toast, squirt guns and shit, and I was distracted by all the naked women walking around. It wasn’t a movie; it was a party.

With Christmas on Mars, I want people to understand what the movie does to us before they’re sitting there anticipating snow hitting them. The impact of the story needs to hit first. So I’d say yes, but it’ll be a little while into the life of the movie. It’s too delicate to withstand too many distractions for the same reason why you don’t want someone’s cellphone ringing three rows behind you.